BY CASSIDY KLEIN

Flushing and Douglaston were once home to Thomas Merton — a Catholic mystic, poet and social activist whom many consider to be one of the greatest spiritual thinkers of the 20th century.

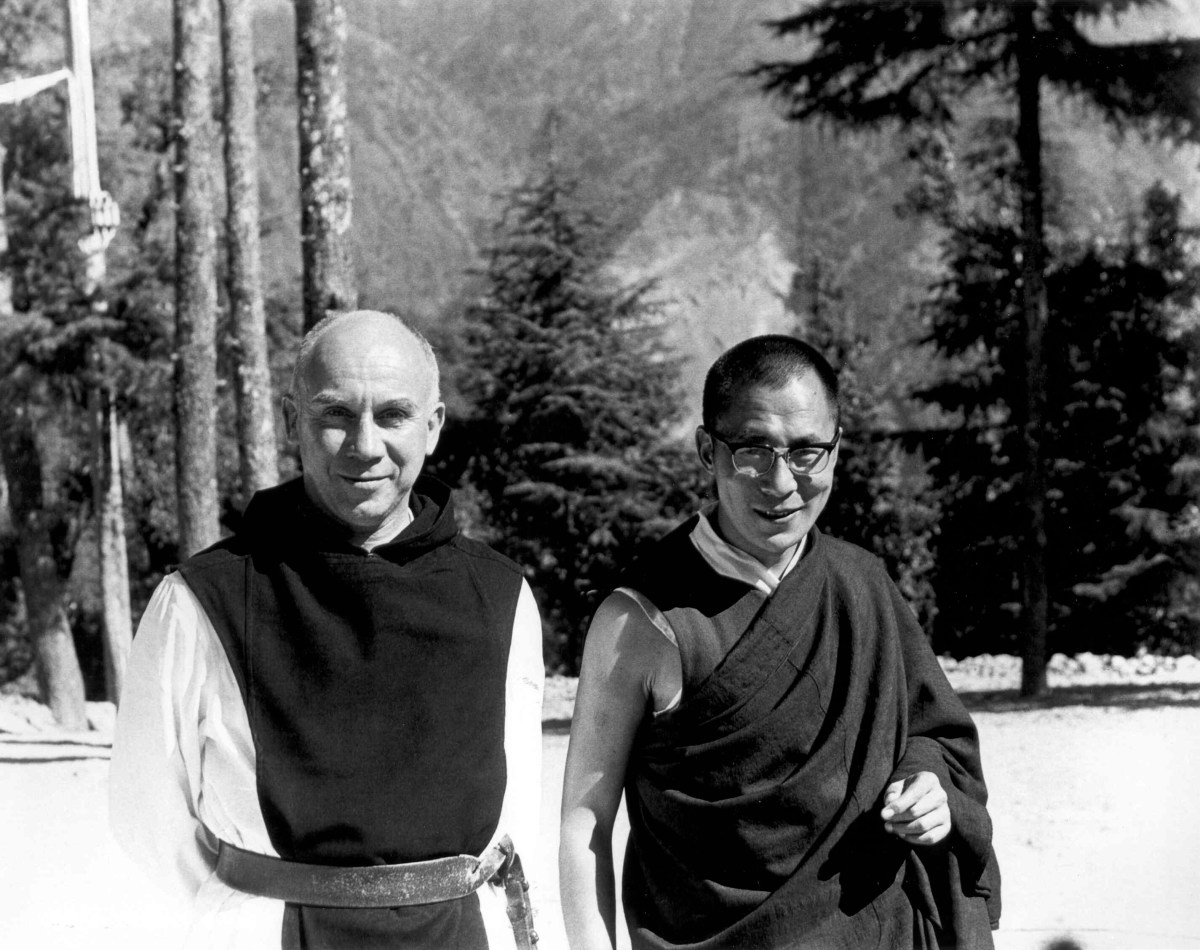

Merton lived as a Trappist monk in Kentucky and wrote more than 60 books and hundreds of articles over his lifetime. His writings touch on a range of topics from monastic spirituality to social justice issues. His autobiography, “Seven Storey Mountain,” has sold more than one million copies.

Dec. 10 will mark the 50th anniversary of Merton’s death and his “prophetic voice” still speaks to millions of people throughout the world.

“Merton forced me to confront the question that I had no answer for,” said Jackson Heights resident Doug Hertler. “And that question was: ‘Who Am I?’”

Hertler, an actor and New York City tour guide, wrote a one-man show called “Merton and Me: A Living Trinity,” which was performed for the first time in September at Corpus Christi Catholic Church on the Upper West Side. He created the show as an outlet to reflect on selfhood and identity through the writings of Merton.

“Merton taught me that it’s possible to live a rich, prayerful interior life and be fully engaged with the challenges that society faces,” Hertler said. “There is a way to take your yearning that you have inside of you to see the world become a kinder, more unified place, and you can do something about it no matter what your vocation is.”

Merton was born in 1915 in Prades, France. One year later, due to the onslaught of World War I, the family moved to an old house in Flushing on Elder Avenue. Merton writes in Seven Storey Mountain that “it was a small house, very old and rickety, standing under two or three high pine trees, in Flushing, Long Island, which was then a country town.”

His father, Owen Merton, was an artist who painted many scenes of Long Island, including “Snow-Buffeted House in Flushing, N.Y.”

Merton moved back to Europe with his father after his mother died when he was still a child. He frequently returned to Douglaston to visit his grandparents at their home located at 241-16 Rushmore Ave. in the summers.

During one of those summers, he attended Zion Episcopal Church — located at 243-01 Northern Blvd. — where his father had been an organist. He also went to the Quaker Meeting House in Flushing — located at 137-16 Northern Blvd. — as he began to seriously wrestle with spirituality.

In 1935, Merton entered Columbia University and converted to Catholicism while there. At age 27, he entered the Abbey of Gethsemani and lived a monk for the rest of his life. He continued to write about spirituality and current events through a social justice lens.

Father Daniel Horan, a Franciscan Friar and Thomas Merton Scholar, said that New York City was an “anchor for [Merton’s] understanding of Christian social justice.”

Merton’s writing on violence and peace, white privilege and structural racism are still deeply relevant today, Horan said.

“Merton said if we want to work for peace, we need to address the fear and violence in our own hearts first,” said Horan. “He wrote that the root of all war is fear. I think that’s powerful in an age where there is so much division, so much hostility. He also makes a very strong claim about the Christian’s role in racism, particularly white Christians, and the responsibility they have to recognize that.”

Merton’s spiritual breath lingers in Queens in people like Hertler who are inspired by him to love those on the margins and dwell with “the most difficult, and life-giving, questions we face as humans.”

“I’m trying to, in my own way, bring the depths of Merton’s spiritual life back into the city as I talk to groups and mention his name to anyone who has ears to listen,” Hertler said. “[Merton] recognized the value and the importance and intimacy and love and joy of communication… in seeing the world through the eyes of a person who views things differently than us.”

Merton leaves us with a challenge to love, Horan said.

“Love is the reason for my existence, for God is love.” Merton writes in his book, “The New Seeds of Contemplation.” “Love is my true identity. Selflessness is my true self. Love is my true character. Love is my name.”