Wyckoff Avenue, which acts as the borderline between Ridgewood and Bushwick, is named after one of the first influential families in Brooklyn and Queens.

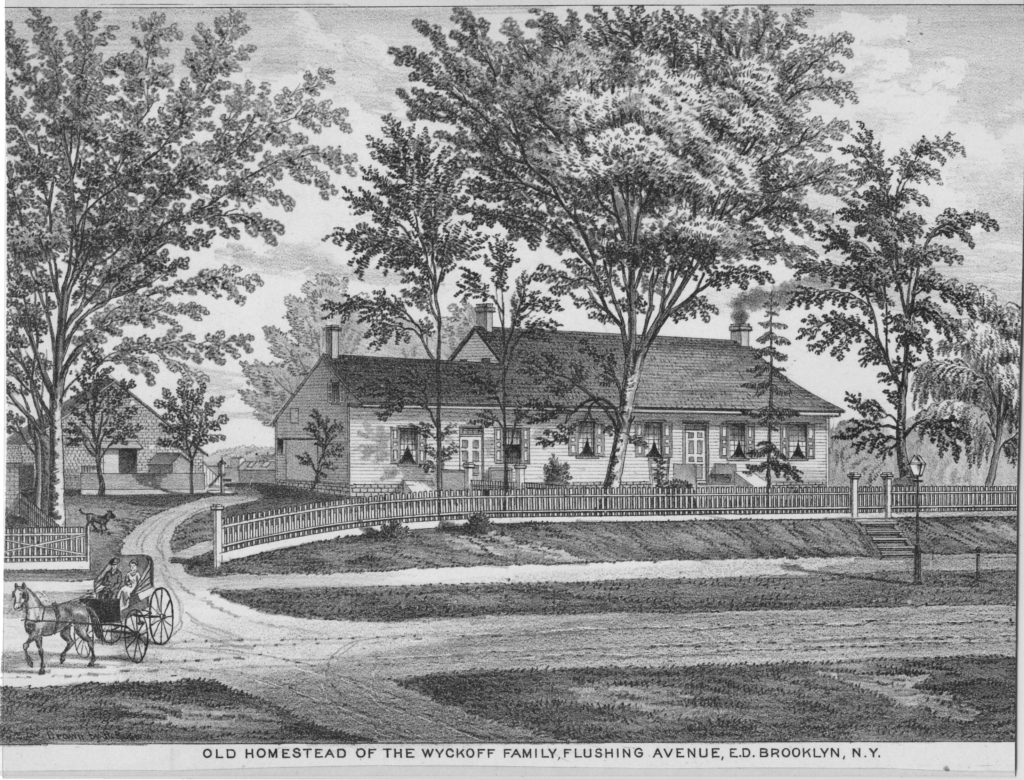

In 1765, Nicholas Wyckoff, who was born in 1743 at the Wyckoff Homestead in Canarsie, Brooklyn, purchased the Schenck Farm in colonial Newtown (present-day Ridgewood). The farm spanned nearly 200 acres in an area bounded today on the north by Flushing Avenue; on the west by Ridge Road (later renamed Wyckoff Avenue); on the east by Cypress Avenue; and on the south by Cooper Avenue.

A farmhouse constructed in 1721 by Johannis Schenck, from whom Wyckoff purchased the farm, was located at what is now 1325 Flushing Ave., along with several barns. The farmhouse was torn down in about 1970 to make way for a factory.

The Wyckoff family came to America in 1636, when New York was known as the Dutch colony of New Netherlands. Pieter Claesen Wyckoff constructed a wood farmhouse on Canarsie Avenue in 1637, at what is now the Clarendon Road and Ralph Avenue intersection in Brooklyn. Still standing, the house is the oldest in New York state and possibly the oldest wood-frame home in the United States.

Great Britain, of course, took control of New Netherlands from the Dutch in 1664 and renamed it New York. The Wyckoffs, no less, remained in the colony. Nicholas Wyckoff was the fifth generation of the family in America.

Besides owning the Schenck Farm, Nicholas Wyckoff also owned 140 acres near what is today Fresh Pond Road, also in Ridgewood.

New York had been under English control for more than a century when Wyckoff had purchased the Schenck farm. However, tensions were simmering between the colonies and the British. Americans were becoming more and more disenchanted by the taxes imposed by the English government. The English insisted the taxes were necessary to cover the costs of the French and Indian War, and for the stationing of troops in America to protect the colonies from attack by the French.

On Dec. 29, 1774, a group of Whigs (patriots) from the township of Newtown (which covered much of Ridgewood, Glendale, Maspeth, Middle Village, Forest Hills and Elmhurst) met and formed a committee of 15. They reaffirmed their loyalty to King George III but protested the taxes without representation as the colonies had no members in English Parliament. The committee also formally approved the proceedings of the First Continental Congress, a group of delegates from the 13 American colonies who met in Philadelphia to discuss, debate and resolve common issues.

Two weeks later, on Jan. 12, 1775, the Tories (loyalists) of Newtown township held a meeting and disavowed the Whig committee’s meeting. Among the 57 Tories were Charles and John Debevoise, John Van Alst Sr., John Morrell, Dow Van Duyn, Jeremiah Remsen and John Suydam. It was obvious that the township was divided on this important issue.

John Morrell’s farm was one of those the British would occupy after the Battle of Long Island through the end of the war. He was a grandson of Thomas Morrell, who built Middle Village’s Morrell House a decade before George Washington was born.

The problems with England worsened and, as a result, in April 1775, skirmishes broke out between the British and colonists in the Massachusetts towns of Lexington and Concord. The American Revolutionary War had begun. In May, the Continental Congress met in Philadelphia and assumed supervision of the militias in the various colonies, appointing George Washington as commander in chief of the Continental Army.

On Nov. 7, 1775, the various townships in Queens County (which also included present-day Nassau County) voted as to whether to send deputies to represent the county at the next meeting of the Continental Congress. The Whigs of Newtown outvoted the Tories 100 to 55, but the final tally of the entire county went the Tories’ way, with 788 against sending deputies and 221 for sending them.

The failure of Queens County to send deputies angered the Congress, which sent a militia force of 900 men to Queens in January 1776. The militia arrived in Newtown, went to the farmhouses owned by Tories and sought to disarm them and take an oath of allegiance to support the Continental Congress. Many of the Tories, however, fled before the militia arrived at their homes. The troops wound up seizing almost 1,000 muskets along with lead pellets and gun powder.

After the Continental Army surprised the British with victories at Fort Ticonderoga and in Boston, the British forces, under General William Howe, evacuated 9,000 soldiers and 1,000 Tories and headed for Halifax, Nova Scotia. But General Washington quickly realized they weren’t in retreat; they were getting ready for an even bigger battle.

Washington surmised that the British would plan an attack on New York City to secure a base of operations that could command the Hudson Valley and the Delaware River Valley. This would effectively split the colonies in half, north and south — a potentially fatal move for the colonists’ cause.

With that in mind, Washington sent the small Continental Navy to New York and moved his Army there. In June 1776, the Continental Congress — a month before formally declaring independence from Great Britain — authorized the call up of 19,800 men from the militias to the Continental Army. These included the militias on Long Island. Nicholas Wyckoff, though he had six children and a large farm to work, volunteered.

Washington prepared for the attack by having his men dig trenches on the western end of Long Island. By June, British ships started appearing off Sandy Hook, NJ. Troopships were arriving from England, with Hessian mercenaries from Germany. General Howe returned with his army from Halifax and had recalled additional troops.

By the third week of August, the British were ready to move against the Continental Army, entrenched on the heights in Brooklyn. The British used barges to ferry their troops across from Staten Island to Gravesend Bay. The Hessians moved forward with a frontal attack, and the British troops, who had marched to the east, came up from behind the American lines controlled by General John Sullivan.

The result was a disastrous defeat for Americans. Some escaped by small boat across the East River at Fulton Ferry to Manhattan, moving in a fog at night, before heading north to reassemble. Nicholas Wyckoff was one of those fortunate escapees.

The 17th Light Dragoons from the British Army scoured the township of Newtown seeking militiamen who had escaped from the battle. While searching the Wyckoff Farm, the British troops wanted to burn the house and barns because of Nicholas Wyckoff’s participation in the battle against them. Antie Wyckoff, his wife, prevailed on the British officer to spare the buildings. Instead, they took all the cows.

She also persuaded a Hessian officer to try and get the cows back so her children could have milk. The Hessian managed to retrieve all but one of the cows.

The British maintained a military presence on Long Island until the Revolutionary War ended in 1783. We’re not exactly certain when Nicholas Wyckoff returned to his Newtown farm, but it was probably in 1777 or 1778. After signing the Treaty of Paris that formally gave the Americans the independence for which they fought, the British Army left Newtown for good, taking thousands of Tories from Queens County with them to Canada.

Needing money, Nicholas Wyckoff sold 70 acres of land on the west of Fresh Pond Road on Oct. 28, 1779, to John Debevoise for 575 pounds (or $20 per acre). Two years later, he sold to Debevoise another 70 acres of land on the east side of Fresh Pond Road.

After his first wife died, Nicholas Wyckoff remarried in 1780 and had four children with his second wife. In 1808, in addition to running his farm, he became sheriff of Queens County.

Wyckoff died on May 29, 1813, at the age of 70. He left his property to his two sons, Peter and Nicholas Jr. On June 11, 1814, they agreed to divide the land amongst themselves in Newtown township, Queens and Bushwick township in Brooklyn, with Nicholas Jr. retaining the original Flushing Avenue homestead.

Nicholas Jr. had a son, Peter, born on Feb. 27, 1828. Upon Peter’s death in 1910, he was still living in the original homestead where he had been born — and was the last of the Wyckoff family to live in that home.

The Wyckoff family heirs, starting in about 1860, sold off property from the original farm. Eventually, houses were built in the area on the Ridgewood/Bushwick border that were given the nickname Wyckoff Heights.

Source: The April 28 and May 5, 1983, issues of the Ridgewood Times.

* * *

Share your history with us by emailing editorial@ridgewoodtimes.com (subject: Our Neighborhood: The Way it Was) or write to The Old Timer, ℅ Ridgewood Times, 38-15 Bell Blvd., Bayside, NY 11361. Any mailed pictures will be carefully returned to you upon request.