As hard as it may be to imagine Ridgewood and surrounding neighborhoods as mostly farmland, it may be harder still to comprehend life in New York City without a clean, reliable water system.

The first residents of our community depended on fresh water ponds and streams flowing through the area as their primary source of water; those ponds disappeared long ago due to development. It wouldn’t be until the early 19th century that the area would have the network of pipelines, mains and faucets that we now take for granted.

But fresh ponds weren’t the preferred water option for the earliest settlers of colonial Newtown, which would later become Ridgewood, Glendale, Maspeth and Middle Village. Spring water was highly prized because it was cleaner than pond or stream water.

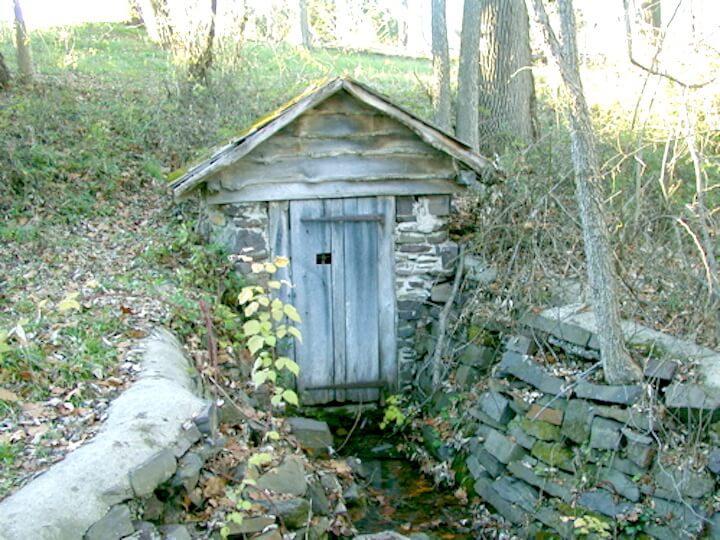

If a natural stream was discovered, it was utilized by building a spring house over it to prevent animals and birds from soiling the water. Because a supply of good water was so important, usually the farmhouse would be built near the spring.

The surplus water would flow out of the spring house as a stream which was used by farm animals. The spring house also made it easier for the farm and his family to draw water during the winter time.

If no spring was available, the early settlers resorted to digging wells, generally about five or six feet in diameter, and — depending on the area’s water table — anywhere from 10 to 40 feet deep. In some cases, it was necessary to go even deeper to find fresh water.

These wells drew on the ground water or “first water” as it was called. If the well was dug through sandy soil, it was necessary to line it with fieldstone set with natural limestone mortar to prevent the well’s walls from caving in.

The fieldstone wall was extended about three feet above the level of the ground to prevent surface water from entering the well. As you might imagine, the method for retrieving well water was very basic, with a bucket attached to a long rope lowered and raised with a crank attached at the top of a windlass.

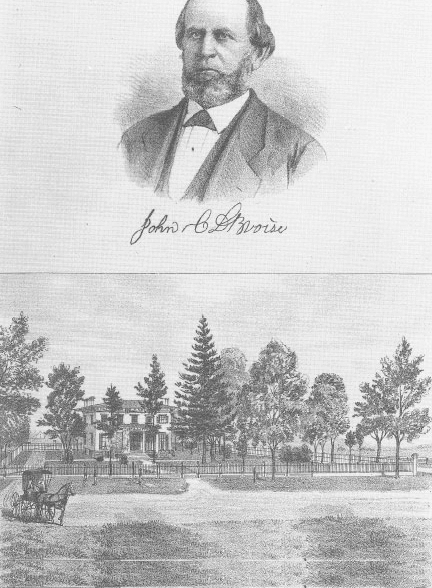

The Moses Debevoise Farm located on the west side of Old Fresh Pond Road (now Cypress Hills Street) just north of Myrtle Avenue, used a well dug in 1723 that was still supplying good water until 1899, when the farm was sold.

(Robert Eisen Collection)

Travelers on the dirt roads that ran through the area back then usually carried a container of water or would use public wells dug along highways. Horses would be watered and rested at public wells.

A large public well in our neighborhood was once located at the corner of Dry Harbor Road (now 80th Street) and Cooper Avenue in Glendale; it was dug in the 1700s.

Wells were generally dug near farmhouses but in a direction away from the privy or outhouse to avoid contamination. During periods of severe drought, some wells would run dry, creating a crisis for the farmer and family.

In later years, driven wells equipped with hand pumps came into use. They went much deeper for their water supply which better insured water during a drought and reduced the risk of contamination.

Catching the rain

The earliest farmhouses in present-day Ridgewood had thatched rooftops. When wood shingles eventually replaced thatched roofs, some farmers used cisterns to supplement their water supply by catching rainwater. Cisterns, or large tanks, were dug in the ground, comprised of fieldstone set with mortar and a wooden cover.

During the colder months of the year in a heavy rainstorm, farmers would wait an hour or so allow rain to clean off the roof and divert the valve in their downspout and channel the water into the cistern. When the rain stopped or the cistern was full, the valve was turned to its normal position to allow rain water to spill on the ground.

Cistern water was used for laundry and bathing and, if necessary, for drinking in the event fresh water was scarce. Rain water, however, was not used during the summer due to the risk of algae contamination.

Proving that what was once old is eventually new again, recycling rain water is again a popular trend among the eco-friendliest New Yorkers. The Department of Environmental Protection (DEP), in recent years, launched a program in which homeowners are provided rain water barrels to deposit runoff from their rooftops; this water can be used to feed nearby plants and trees, or to wash cars and sidewalks.

As the population grew and homes were built closer together around our community, it became practical to consider having a water works supply water under pressure to houses through pipes. An artesian well was drilled anywhere from 100 to 2,000 feet deep with reach the artesian aquifer containing groundwater.

Some of the aquifers extended several hundred miles and filters very slowly through sand and soft limestone; in some cases, it might take the water 15 to 20 years just to travel one mile.

Another method of supply was to obtain fresh water from distant spring-fed ponds, streams or rivers and bring them into the community through a series of covered or open aqueducts to reservoirs, where the water was stored until needed.

Building more than a supply

In May 1849, the City of Brooklyn — which had been incorporated 15 years earlier — made the move to build its own water network. The city was spurred through a severe cholera outbreak that killed one in every 155 inhabitants. The epidemic was blamed on contaminated fresh water sources.

In 1849, the city conducted engineering surveys to build a water system and ensure an ample supply of pure water for Brooklyn residents. On Jan. 1, 1855, the city added the communities of Bushwick and Williamsburg, bolstering its population to 205,250 — making Brooklyn not only the third-most populous city in the U.S. at the time, but adding to the pressing need for a reliable water supply.

In 1855, the City of Brooklyn recommended the establishment of the Nassau Water Company, which the State Legislature officially chartered that year. The Nassau Water Company, in its charter, was authorized to issue $3 million in capital stock and had permission to borrow another $3 million if necessary.

The goal was to pipe in spring water from eastern Long Island — present-day southeast Queens, Nassau and western Suffolk counties — into Brooklyn to satisfy the water needs of Brooklyn residents.

The City of Brooklyn was authorized to buy up to $1.3 million in stock and issue and sell bonds to pay for it. The directors moved quickly and the H.S. Wells and Company firm was awarded a contract of $4.2 million to build reservoirs, aqueducts, engine houses and 120 miles of pipeline and 800 fire hydrants.

And the heart of this new water system would be a massive reservoir located on a hilltop on the present-day Brooklyn/Queens border that would give our neighborhood more than just drink, but also its identity: the Ridgewood Reservoir.

Visit QNS.com next week to read more about the Ridgewood Reservoir’s development, and its continued impact on life in our neighborhood.

Reprinted from the Jan. 15, 2015 issue of the Ridgewood Times.

* * *

Share your history with us by emailing editorial@ridgewoodtimes.com (subject: Our Neighborhood: The Way it Was) or write to The Old Timer, ℅ Ridgewood Times, 38-15 Bell Blvd., Bayside, NY 11361. Any mailed pictures will be carefully returned to you upon request.