Over the next two weeks, we’re going to take a look back at two projects that could have dramatically altered the landscape of our neighborhood in Queens — but never came to be.

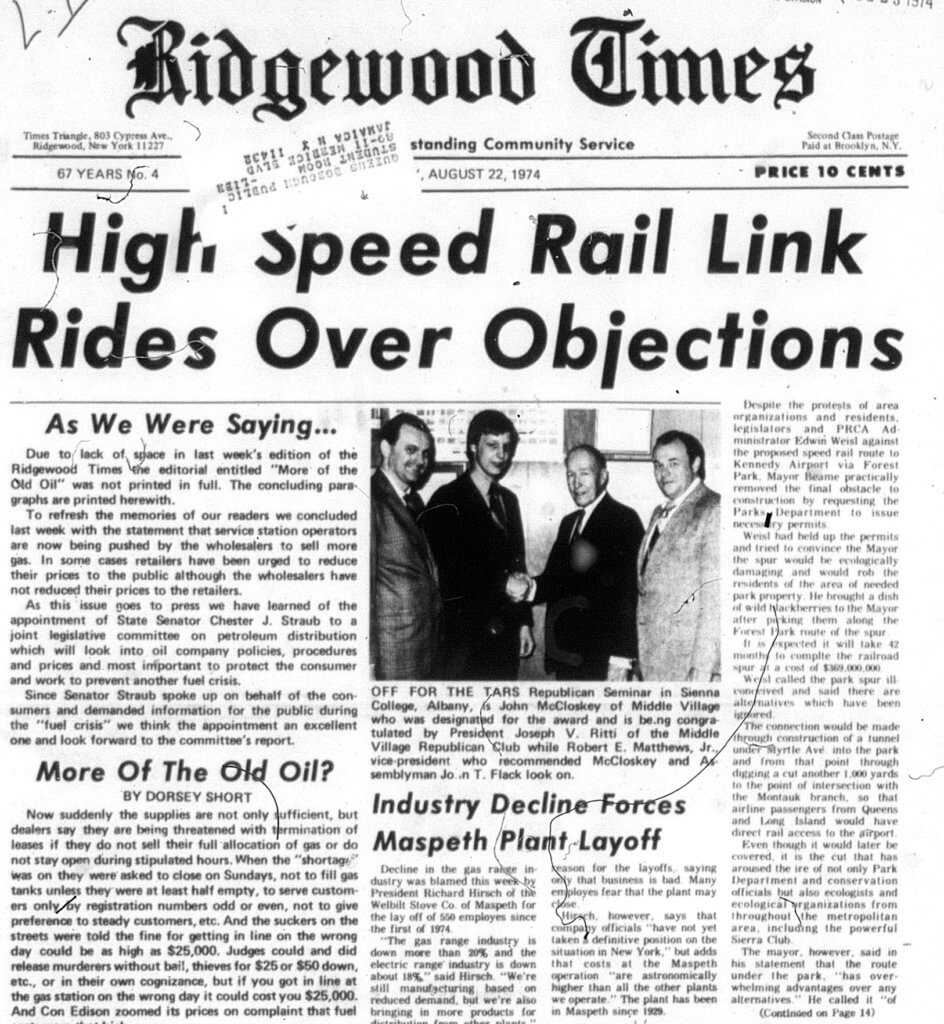

The first project looked like an almost certainty when the Ridgewood Times published a front page article about it in the Aug. 22, 1974, issue.

For five years, up to that point, the city had its eye on creating a high-speed rail link between Manhattan and John F. Kennedy International Airport. According to a 1969 plan, the city wanted this line to run primarily along the Rockaway Beach branch of the Long Island Rail Road, which was taken out of commission back in 1962.

To complete the link, however, the city planned on digging a huge tunnel through Forest Park connecting the defunct Rockaway Branch with the LIRR’s Montauk Branch in Glendale. The proposal raised the ire of community residents, who saw the idea as something that would forever change Forest Park’s ecology — and not for the better.

But it was then-Mayor Abraham Beame who had the final word about the project’s fate — and on Aug. 22, 1974, the Ridgewood Times reported that Beame was ready to move on the plan, whether the community liked it or not.

Here’s an excerpt of the story:

Despite the protests of area organizations and residents, legislators and [Parks and Recreation] Administrator Edwin Weisl against the proposed speed rail route to Kennedy Airport via Forest Park, Mayor Beame practically removed the final obstacle to construction by requesting the Parks Department to issue necessary permits.

Weisl has held up the permits and tried to convince the mayor the spur would be ecologically damaging and would rob the residents of the area of needed park property. He brought a dish of wild blackberries to the mayor after picking them along the Forest Park route of the spur.

It is expected it will take 42 months to complete the railroad spur at a cost of $369,000,000.

Weisl called the park spur ill-conceived and said there are alternatives which have been ignored.

The connection would be made through construction of a tunnel under Myrtle Avenue into the park, and from that point through digging another 1,000 yards to the point of intersection with the Montauk branch, so that airline passengers from Queens and Long Island would have direct rail access to the airport.

Even though it would later be covered, it is the cut that has aroused the ire of not only Park Department and conservation officials, but also ecologists and ecological organizations from throughout the metropolitan area, including the powerful Sierra Club.

The mayor, however, said in his statement that the route under the park “has overwhelming advantages over any alternatives.”

Around the same time, The New York Times reported about the proposed high-speed rail line to JFK and included comments from residents in Glendale and Forest Hills who were opposed to the plan.

The New York Times article noted that the Forest Park tunnel would have cut through a bridle path used by hundreds of people going horseback riding through the park from the nearby Park Side Stables on 70th Road.

Residents of the high-rise Forest Park Crescents co-op also feared the project, The New York Times reported. The high-speed line would have emerged from a tunnel located about 20 feet away from the building, potentially exposing residents to greater noise and vibrations from regular train activity.

Though the project made sense at the time, the city soon found itself mired in the greatest economic crisis of its history. By 1976, with an economic downturn in place — and staunch opposition from Queens residents who objected to the Forest Park tunnel — it no longer made sense to move ahead with the plan.

That year, the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey, which operates JFK, scrapped its support for the high-speed rail link, and the plan was officially dead.

‘The Train to the Plane’

Two years later, in 1978, the MTA came up with an alternate plan for getting commuters to and from JFK using existing subway lines.

The JFK Express was advertised as “The Train to The Plane,” and ran from 57th Street in Midtown Manhattan through Brooklyn and Queens to Howard Beach, making just eight stops along the way.

Once at Howard Beach, JFK Express passengers boarded an express bus to the terminals. Passengers paid a slightly higher fare for the special train service.

Similar to other subway lines which used a colorful logo, the JFK Express logo was a turquoise circle with a white jet plane in front of it. The MTA also ran a very catchy jingle for “The Train to The Plane” in TV advertisements.

It was not the high-speed link that Beame and others envisioned, and after 12 years of limited success, in 1990, the JFK Express was grounded for good.

A few years later, the Port Authority built the AirTrain, a monorail linking the JFK terminals to both the Howard Beach station on the A line and the Jamaica Long Island Rail Road station.

Still lying in wait

Meanwhile, the Rockaway Beach Branch remains abandoned — and the subject of many ideas on what to do with it.

Over the last half-century, the 3.2-mile line between Rego Park and Ozone Park has become naturally reforested with all kinds of plant life. For more than a decade, activists have sought to transform the former rail line into a public park akin to Manhattan’s High Line Park — created on a dormant, elevated rail spur that’s become one of the most popular green spaces in the borough.

The Trust for Public Land secured state funding for the creation of what’s called the “QueensWay.”

Conversely, transit activists in south Queens also conducted a study for potentially reactivating the Rockaway Beach branch for rail service to cut the commute times for thousands of local residents heading to Manhattan each day on the A or J/Z lines.

As the future of the Rockaway Beach line remains uncertain, nature continues to dictate its present. A number of adventurous urban explorers have walked the line and documented its current state. In many spots, you can still see the original railbeds, with trees and plants shooting up around the ties and steel beams.

Next week, we’ll examine another rail project that never came to be: a proposed subway line on the LIRR’s Montauk Branch from Sunnyside to Jamaica.

* * *

If you have any remembrances or old photographs of “Our Neighborhood: The Way It Was” that you would like to share with our readers, please write to the Old Timer, c/o Ridgewood Times, 38-15 Bell Blvd., Bayside, NY 11361, or send an email to editorial@ridgewoodtimes.com. Any print photographs mailed to us will be carefully returned to you upon request.