BY BEN VERDE

They need a jump start!

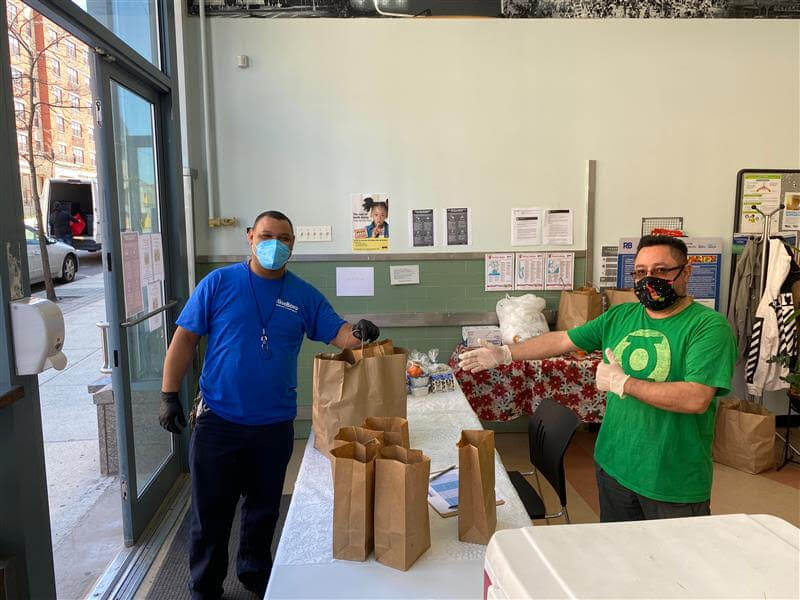

Services that deliver meals to homebound seniors have seen a spike in demand under the state’s stay-at-home order, as elderly New Yorkers seek safe ways to stay fed without venturing outside. But, with limited resources and no increase in funding on the horizon, it is getting increasingly difficult for many to meet demand.

“We’ve seen close to a 20 percent increase in the past seven weeks,” Todd Fliedner, deputy executive director of the Bay Ridge Center told Brooklyn Paper. “This is a trend we just see as continuing.”

Programs like Fliender’s often held congregate meals in senior centers prior to the coronavirus pandemic, but have shifted to delivery-only as those they serve hunker down inside — many of whom were offered a citywide meal service run by the Department of Aging. But, program directors say, many of the city’s seniors prefer the local, nonprofit-run meal services, because they find their specific dietary needs are met and deliveries are more reliable.

“If they have one client who is say, a vegetarian, and also has trouble chewing their food, a local organization is able to respond to that and make sure they receive their food,” said Tara Klein, a policy analyst at United Neighborhood Houses, who said that the larger-scale meal programs tend to be more of a “one-size-fits-all” operation.

To boot, seniors who switched over to the citywide service in the early days of the stay-at-home order reported poor communication, a lack of coordination and low-quality meals. Some seniors who signed up for the program never received meals at all, according to Scott Short, CEO of RiseBoro Community Partnerships, a home-delivered meal provider that operates out of Bushwick.

“The quality of the meals that they were getting was really below the standards of what we find acceptable,” said Short.

The shortcomings of the citywide program have exacerbated demand among the smaller community programs, according to the head of RiseBoro, who has seen a nearly 30 percent increase in deliveries since the pandemic began. The program currently services about 1,800 people, Short said — a combination of both new clients, and those who are not receiving their deliveries from the city.

Despite the increased demand, programs like RiseBoro and the Bay Ridge Center are operating with the same flat level of funding from the city as in pre-pandemic times, and are pushing for emergency funding from the Department of Aging.

The Bay Ridge Center has had to hire more staff, add an additional delivery route, and purchase more food than usual, according to Fliedner. Scott says RiseBoro, which is also increasing its food production and providing its workers with time-and-a-half hazard pay, will only be able to operate at its current rate without emergency funding until the end of its fiscal year on June 30.

“We’re basically fronting it and hoping that the city does the right thing and reimburses us,” Scott said. “We’re putting our own finances on the line to do what we think is the right thing for these essential workers.”

In a letter to Department of Aging Commissioner Lorraine Cortés-Vázquez, Manhattan Councilwoman Margaret Chin, chair of the Council’s Committee on Aging, laid out a demand of $26.2 million in funding for home-delivered meal programs, which Chin says is necessary to keep the programs from failing.

“The city must invest in the HDM program to ensure that the COVID-19 pandemic does not do further harm to our city’s older adults than it already has,” Chin wrote in the letter dated May 1. “This funding need is urgent.”

The Department of Aging has not indicated yet whether it will be able to provide the emergency funds.

“We are in receipt of Council member Chin’s letter and are reviewing,” said department spokesperson Suzanne Myklebust. “Providing food assistance to New Yorkers during COVID-19 is a high priority for the city.”

While they await funds, meal providers are reflecting on their relationship with the city — something, Scott said, has been problematic for years before the pandemic. Contractors have not received increased funding per-meal in close to a decade, the program director said, all the while expenses for food, fuel and labor have gone up, resulting in most providers losing money on their city contracts.

“I think COVID has helped shine a light on this problem,” Scott said. “But it’s really a more endemic problem that goes back years.”

This story first appeared on brooklynpaper.com.