By Chris Fuchs

In a skittish, at times rambling statement made before State Supreme Court Judge Barry Kron, Jose Feliciano, 25, ardently denied that he fatally shot Steven Julien, a 23-year-old single father from Hempstead, L.I., during an argument at a drag race outside the Blue Bay Diner in 1998.

“You're honor, I didn't take Steven Julien's life,” Feliciano said, sobbing hysterically, his voice shrieking. “Your honor, I was at the wrong place at the wrong time.”

The judge, saying he doubted that the case would be overturned should it be appealed, sentenced Feliciano to a total of 37 1/2 years to life in prison, based on his criminal history of assault as well as his conviction of depraved indifference murder, robbery, reckless endangerment and criminal possession of a weapon in this case.

“In terms of Mr. Feliciano's protestations of innocence,” the judge said, “I have no doubt that this conviction will be sustained.”

In an interview, Barry Weinrib, the assistant district attorney who prosecuted the case, said that he, too, was certain that Feliciano was convicted justly.

“I don't have a way of going back there myself, but this is as strong as a case gets,” Weinrib said.

But Alberto A. Ebanks, the defense attorney, said in an interview that he was sure Feliciano had been convicted wrongly, adding that he had filed a notice of appeal with the court. Ebanks said, however, that another attorney would handle the appeal if one should be filed.

“For this guy from the first day I met him until the day he was sentenced, the story has been the same,” he said. “If I had the wherewithal to appeal, I would. But I firmly believe that there is at least one major issue that could turn this case around.”

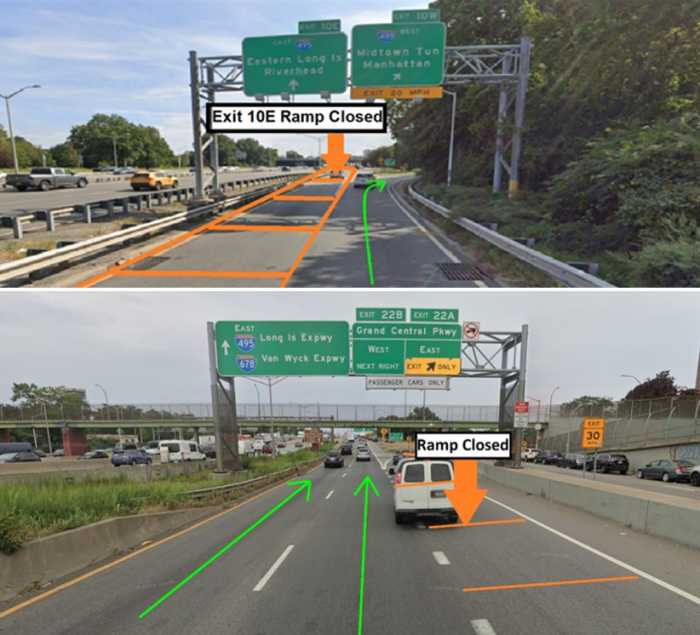

On Oct. 11, 1998, Julien, a cleaner for the Long Island Rail Road, and his girlfriend left Hempstead and traveled to the city in search of a drag race, Julien's father, Norris, said. After driving around for several hours, he said, the couple eventually came upon a race on Francis Lewis Boulevard, close to the Long Island Expressway.

Francis Lewis Boulevard is an ideal strip for drag racing: a wide street bisecting the borough, desolate by nightfall. By the time Julien and his girlfriend had arrived, the father said, there were nearly 100 spectators gathered near the Blue Bay Diner at 58-50 Francis Lewis Blvd. Among them was Jose Feliciano, a 23-year-old man whose criminal record already included three assault convictions.

During the race, Feliciano and Julien's girlfriend's brother, Coron Graham, got into an argument over a comment that Graham thought Feliciano had made towards his girlfriend. So Graham popped his trunk and took out a baseball bat, threatening Feliciano with it. Julien stepped in and grabbed the bat away from Graham, the father said. Moments later, Feliciano pulled alongside the men and opened fire, hitting Julien twice and killing him, the Queens district attorney, Richard A. Brown, said.

Feliciano fled in Graham's car, the district attorney said, but after a high-speed chase through Queens and Brooklyn, the police caught Feliciano and arrested him.

At the sentencing Monday, three of Julien's relatives – his mother, his father and his uncle – and two co-workers from the Long Island Rail Road sat shoulder-to-shoulder in the second row. Feliciano's wife, her children and another family member, all of whom left immediately after the sentencing, sat in the last row. Before the judge imposed sentence, Julien's mother, Kathleen, 57, addressed the court.

“All I think about is Stevie,” she said. “Commuting from Brooklyn to Queens to Long Island, everyday, all I see is Stevie. I think I did the very best I could to keep Stevie out of danger. But I never told him about predators like the one in this courtroom.”

Julien's uncle, Rupert Merrique, 46, also addressed the court, by turns consulting notes he had placed on the podium and training his eye on the judge.

“There was no party, no nothing like that,” Merrique said of the days after the conviction last month. “There was just a sense of relief that the trial was over and that the person who was found guilty would go to jail for a very long time…” Merrique paused, then took a breath, sniffling in between.

At the end, Feliciano was given the chance to address the court, before the judge imposed sentence. In cadences that rose and fell, Feliciano insisted in a wandering four-minute statement that he had been wrongly convicted. He spoke about his father, who Feliciano said was murdered when he was a child, about his wife and children, and about how he tried to be a good father.

“I wish I could give my life to bring him back,” he said, referring to Julien. “I wish right now that you could give me the electric chair because I don't want to go to jail.”