By Dustin Brown

The Queens County Democratic Organization’s odds of getting its judicial candidates on the bench are not just favorable, they’re overwhelming.

Every candidate who has run on the borough’s Democratic Party line for a spot in New York City Civil Court or State Supreme Court has won in every election since 1990, the span examined in a TimesLedger analysis.

The party’s unblemished record means the process of choosing judges is less an election by the voters than a selection by the Queens County Democratic Organization, political insiders and watchdogs say.

They contend it is an easily abused system that can serve as a pool of political patronage where the nod goes to party faithful ahead of qualified candidates.

“The selection of judges is a political rewards system by and large, and the politicians do not want to lose this important plum,” said Judge Leo Milonas, the president of the Association of the Bar of the City of New York and a former chief administrative judge.

The threat of abuse has already emerged as a reality in Brooklyn, where District Attorney Charles Hynes has launched a grand jury investigation into possible corruption in the county’s judicial elections following the recent indictment of a State Supreme Court justice on charges he fixed divorce cases for bribes.

The problems in Brooklyn have added fire to an already growing reform movement that has gathered momentum from Mayor Michael Bloomberg and Chief Judge Judith Kaye, both of whom are strong advocates of change in the election process.

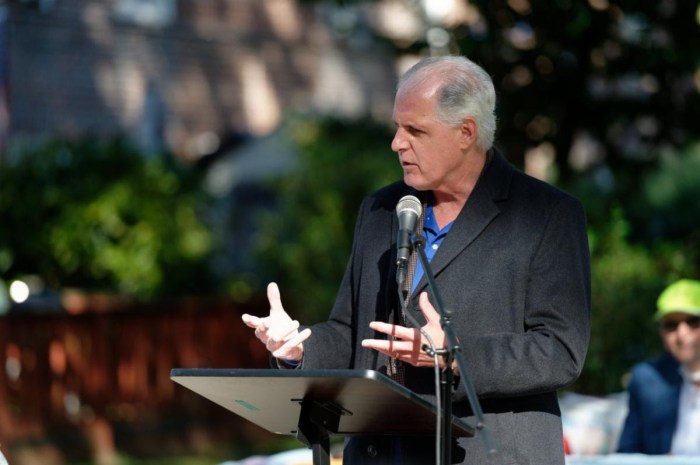

“There is something very wrong in the way many of our judges are chosen,” Bloomberg told the city bar association last month, outlining his vision of a merit-based appointive system to replace elections for the civil and supreme courts.

But the elective process for judgeships enjoys broad support in Queens County, where even the people who perennially stand on the losing side of the system — most notably the Republicans — do not support reforms that would extract the power from the Democratic machine and give it to a politically independent entity.

The final say in choosing judges belongs in the hands of the voters, borough political leaders contend, and few in Queens are willing to give that up.

A Perfect Record

The Democrats’ overwhelming advantage at the polls in Queens is not unique to the judiciary. Republicans are sorely under-represented in every elective office in Queens County, boasting only one city councilman, two state senators and no members of the state Assembly or U.S. Congress.

But the judicial races stand apart in the absolute reliability of the Democratic line in securing victory as well as the sheer inability of a Republican candidate to be elected without Democratic support.

Out of 92 court vacancies in Queens filled by election from 1990 to 2002, every slot went to the candidate listed on the Democratic line.

“It shows you that basically, unfortunately, they’re not real races,” said Perry Reich, an attorney and Republican district leader from Hollis Hills who lost two elections for State Supreme Court in the late 1990s. “In Queens County you cannot possibly win a judicial race unless you have the Democratic line. No ifs and or buts about it. People understand that, and unfortunately the party gains a lot of control that way.”

The unfailing reliability of Democratic victory in judicial races is a consequence of the party’s overwhelming advantage in voter registration — there are four Democrats to every one Republican in Queens — combined with the relative anonymity of judicial candidates. Since most aspiring judges do little campaigning and most voters pay no attention to judicial races anyhow, votes are typically cast on the basis of party affiliation.

A case in point is the election of State Supreme Court Judge Thomas Polizzi. A registered Republican, he ran in 1991, 1992 and 1993 without the Democratic line and lost, but in 1994 the Democrats agreed to cross-endorse him. That year he won.

The only other elected Republican judge presently sitting in Queens is Joan Durante, who was already serving on State Supreme Court when she won the Democrats’ cross-endorsement for re-election in 2001, according to state Sen. Serphin Maltese (R-Glendale), the chairman of the Queens County Republican Party.

Durante was originally elected in 1973 and re-elected in 1987, although whether she had the Democratic Party line in either race is unclear.

But Carolyn Geller, a Republican whom Gov. George Pataki had appointed in July 2001 to fill the State Supreme Court seat vacated by the retirement of Judge Joseph Lisa, did not get the Democrats’ backing for her November bid to stay in the court by election.

“She was far more qualified than any of her fellow candidates who had not sat on the bench,” Maltese said. “But because she was running only as a Republican and a Conservative, she was not able to obtain the votes.”

Becoming a Judge

The path to the bench for any Democrat starts with the Queens County Democratic Organization.

“The first requirement I think is to be a good loyal party member,” said former Queens County Bar Association President Ed Rosenthal, describing his perception of the way borough Democrats choose their candidates. “And the second qualification is to be a good lawyer. But I think that has to be secondary.”

By all accounts the ultimate say in who receives the critical Democratic endorsements lies in the hands of Tom Manton, the Queens party chairman. But his methodology in choosing people is anything but transparent.

Neither Manton nor the party’s executive, Michael Reich, returned repeated phone calls for comment.

“It’s a political process,” said State Supreme Court Judge Richard Buchter, who won a seat on Civil Court in 1987 and Supreme Court in 1992. “If they know you and they feel that you’re somebody who’s competent, that always helps. You have to be active in politics.”

None of the political insiders interviewed for this story said they were aware of any screening committee or formalized protocol that the Democratic organization currently employs to select its judicial candidates.

The most reliable method to win the party’s endorsement, they said, is good old-fashioned networking.

“An individual who is seeking a nomination from a party should be a person that is known to the party,” said Howard Lane of Laurelton, a law secretary in State Supreme Court who received the Democrats’ endorsement for an open civil court seat in this year’s election. “If they don’t know who you are, that makes it that much more difficult to make that connection.”

That means judicial candidates and prospective candidates are frequently seen at fund-raisers and functions for the county organization, where the powerful people are assembled in a single room.

“Those affairs are certainly opportunities to network with people who are part of the selection process,” said Lane, who indicated he would typically attend two to three such events in a given year.

Campaign finance records for the Democratic Party back up that pattern. All of the civil court judges elected in the past three years appeared on a list of contributors to the Queens County Democratic Organization in 2001 and 2002, either as individuals or via their campaign committees. The contributions typically appeared in increments of $250 or $300, the price of a ticket to one of the party’s seasonal fund-raisers.

A candidate puts his name in the running for a judgeship by seeking support from the party’s district leaders — four of whom are elected in every Assembly district — who in turn will lobby Manton. Sometimes candidates will go directly to Manton himself to pitch their case.

Often a judicial hopeful will end up handing his resumé to the district leaders year after year before his name finally comes up.

But candidates sometimes get to skip many of those steps when the party comes to them, offering support for a judgeship as part of a political deal.

A highly publicized example was the 2001 election of Bernice Siegal to the Civil Court. She won the Democratic Party’s endorsement by agreeing to step out of her primary race for City Council against David Weprin, the party’s choice who ultimately won the seat.

“I knew this was an opportunity to provide a high level of public service for New York City, which is what I want to do,” Siegal told the TimesLedger at the time. “They provided me with that opportunity.”

Queens State Supreme Court Judge Frederick Schmidt said the party offered to endorse him for Civil Court in 1992 after he had served many years in the state Assembly and new district lines would have put him up against Assemblyman Anthony Seminerio (D-Richmond Hill).

“They asked me if I wanted to run, and I said yes. I had to think about it,” Schmidt said. “I was not interested. But then when my district was changed and I wouldn’t have the opportunity to represent the same people that I did over the years — it was a very, very difficult decision.”

In the end the party’s nod is subject to a vote: the Democratic district leaders assemble at the party’s designating meeting in May to decide endorsements for Civil Court and other races, while delegates elected to a special judicial convention in September vote on State Supreme Court candidates.

But by that point the candidates have already been selected and the vote is little more than a rubber stamp, insiders say.

Although the city and borough bar associations perform optional assessments of candidates, that only happens after their names have made it onto the ballot. Thus the organization’s choice could fail to win the bar’s approval yet still coast to victory.

Calls for Reform

By handing so much authority to party leaders — who face so little scrutiny in the way they select their candidates — the elective system is mired with flaws that leave it ripe for abuse, critics say.

“The mayor, the city bar, all the people who are concerned about the welfare of the judiciary in our courts and our people feel that we should depoliticize the selection of judges,” said Milonas, the city bar president. “Judges should be screened by independent commissions or screening commissions that are divorced from politics as much as possible.”

Mayor Bloomberg and Chief Judge Kaye are moving to do just that, leading an effort to restore confidence in the judicial election process.

“I am calling on the county leaders of the political parties to commit — right now — to naming broad-based screening panels to evaluate and make public recommendations on all those being considered for a judicial nomination,” Bloomberg told the city bar association in his speech last month. “That commitment would send the clear message that behavior such as that alleged in Brooklyn will not be tolerated.”

The mayor uses a so-called merit system for his appointments to the bench, whereby he selects people only after his committee on the judiciary and the city bar association have approved them — a method he urged the political leaders to adopt as well.

Kaye has likewise appointed a 29-member Commission to Promote Public Confidence in Judicial Elections to examine ways to clean up the system, such as creating new ethics protocols, revamping campaign finance and producing nonpartisan voter guides.

“Public confidence in the judiciary is tarnished by election contests that appear inconsistent with what we value in the judiciary — independence, fairness, impartiality,” Kaye said in her state of the judiciary speech this year.

Legal experts say the political ties that help propel a candidate to the bench are unlikely to influence judges’ impartiality once they don the black robe, by which point they must have divested themselves of their political affiliations.

“Once a judge is elected for 14 years, he’s not so concerned about what the party’s going to think of him,” said Andrew Simons, associate academic dean at St. John’s University Law School. “Nor are party issues going before the judges — usually automobile cases or murder cases having nothing to do with the political system.”

But since the political process offers a less thorough means of screening candidates than an independent committee, bad eggs can slip by more easily.

“You find people who are honorable and you generally don’t get fooled” by employing a screening committee evaluation, Milonas said. “But if people are selected for political rewards, then how much of the integrity and community service and high moral character enters the picture, I don’t know.”

It also comes down to a basic question of quality control.

“When a judge’s attaining office is dependent on his involvement in the political process, that does not necessarily mean you get bad people. But it also doesn’t mean you get well-qualified people,” Simons said. “You get people who have paid their political dues. That obviously stinks in terms of getting the best qualified people.”

Faith in the System

But even the critics of the current system are not confident that the mayor’s proposed reforms would represent an improvement because they suspect it would simply shift the balance of power to another arena that is no less political.

“I’m not sure that the proposed alternatives are better. They sound better. Everybody’s in favor of so-called merit selection,” Simons said. “The question is, who’s determining the merit?”

Simons’ perspective is mirrored in all corners of Queens politics, where people acknowledge the imperfections of the elective process yet refuse to concede the authority of electing judges to another body.

Many regard the Queens system as a grassroots method of choosing the judiciary that is accessible to people of all backgrounds and led by party officials who are ultimately accountable to the voters.

“I think that the elected system helps to give a representation, and I think we have a broader representation now of the general public,” said one Queens judge who asked to remain anonymous. “It’s not a perfect system, but no system is perfect. I’d rather have the people out there than have somebody else choose from the top down.”

Reich defended the borough organization’s selection of judges in a recent interview with a law publication.

“The Queens system has worked well to produce a quality bench that reflects the county,” Reich told the New York Law Journal in May. “No system is free of politics. The mayor’s [system] would put white shoe bar association leaders on the inside of the selection process.”

But the Democrats also have the most to lose with reforms. More telling is the response of the Republicans, who still support elections despite the way it shuts out their candidates.

“[The voters’] choice is minimal, but some minimal choice is better than none at all,” said Maltese, the Republican Party chairman. “If you asked me do you favor elected judges or appointed judges, I would have to say it would be elected judges because I do think the public has some say.

“And in addition the political leaders know that the bottom line is they’re going to have to put them on a ballot. They keep that in mind when they’re picking candidates,” he said.

Indeed, the judges of Queens County enjoy a solid reputation for quality and integrity that is acknowledged across political parties and the legal community.

“The quality of the people who have made it onto the ballots for elections to judgeships in Queens has been pretty good,” said Jeh Johnson, the chairman of the city bar association’s judiciary committee, which evaluates judicial candidates.

In fact, Johnson considers the members of the Queens bench to be as qualified as those selected by the mayor’s commission, which he described as “a model of how it should be done.”

Although the Democratic leaders have the ultimate say, many in Queens trust their judgment and they believe that to give up the elective process would be to sacrifice the borough’s voice in choosing its own judiciary.

“At least Tommy Manton practices in the county and they are lawyers here and they have an inkling of who can do this job,” said Rosenthal, the former president of the Queens Bar.

“He hasn’t done a bad job — I think he’s done a pretty good job for this county. And I ain’t a Democrat.”

Reach reporter Dustin Brown by e-mail at Timesledger@aol.com or call 718-229-0300, Ext. 154.