By Joe Anuta

A new art exhibit at Queens College tells a war story from a different angle — from the perspective of Afghanistan citizens.

The exhibit, called “Windows and Mirrors,” features 45 murals that were painted by artists from the United States and around the world — although three are from Queens — who painted the images on parachute fabric specifically for the exhibit. Many of the murals feature the violence and derelict landscapes that typify the lives of Afghanistan citizens who live in combat zones.

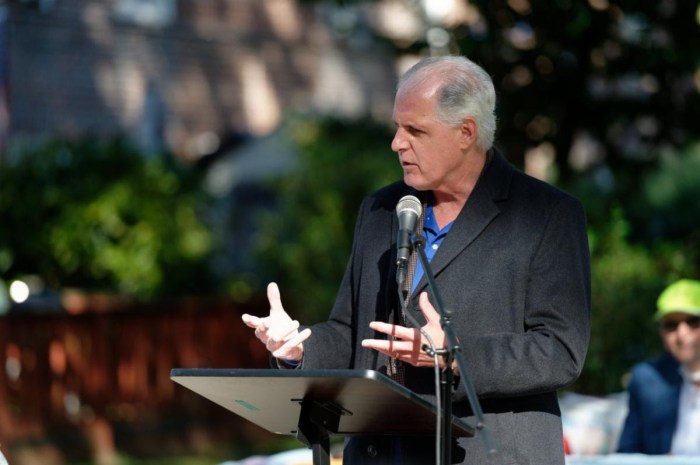

“The human cost of war is the primary theme,” said Amy Winter, director and curator of the Godwin-Ternbach Museum, although she added that other motifs in the exhibit were non-violence as well as harsh treatment of Afghan women by the Taliban in extremist circles.

“This is really an anti-Afghanistan War statement and anti-war in general,” she said.

The 45 murals are four by six feet and hang along the walls of the museum. Some of the murals do not hide their anti-war sentiments, such as “Untitled” by Ohio artist Ashley Scribner, where several portraits of Afghan children look out from the center of the mural. On the top portion a statistic reads: “At least three children were killed in war-related incidents every day in Afghanistan in 2009.” And at the bottom: “When does it stop?”

Others were more subtle, but the message was still clear.

In Lillian Moats’ “Foreshadowing,” children play with their shadows on a flat desert field, but the silhouette of a drone aircraft joins them.

On the other end of the spectrum, the least overt murals depicted parts of Afghan culture, such as Ann Northrup’s “Mountain Kites,” where two children fly kites over a vast, pastel-dappled range of mountains.

Winter said that showing military conflict from the civilian side is important, since in movies and other forms of media war is glorified.

“While I think it’s good to morally support the troops and support people who have gone over there … I think nonetheless that a culture of fear and violence have been really touted by the media, and this is destroying our society,” she said.

But she also did not deny that the exhibit itself depicted violence, although the murals used symbolism instead of glorification of battle scenes.

“Some of the murals depicted scenes of suffering and death to address the senselessness, destruction and loss of war,” she said.

Tucked along a wall on the second floor, the work of some other international artists was featured as well — that of Afghan schoolchildren.

Winter said a teacher had asked them to draw what life was like living through a war.

Many of the pictures were drawn with the characteristic wobbly lines of a second-grader and showed homes crumbling under disproportionately large bombs and misshapen family members who were missing limbs.

The exhibit opened on Dec. 9, and runs through Jan. 30., but Winter said Jan. 20 is a special veterans night. It was commissioned by the American Friends Service Committee.