By Philip Newman

Philip Newman, a contributing writer for TimesLedger Newspapers, was a reporter in UPI’s Dallas bureau when the president was shot.

It was a beautiful day worthy of a visit by the president of the United States that Friday in late November, but would the people of Dallas heartily welcome the first family?

Considering the political atmosphere in Dallas in the early 1960s, it was hard to say.

“Nothing degrading must happen when President Kennedy comes to Dallas,” said Chief of Police Jesse Curry as city officials were planning for the presidential visit.

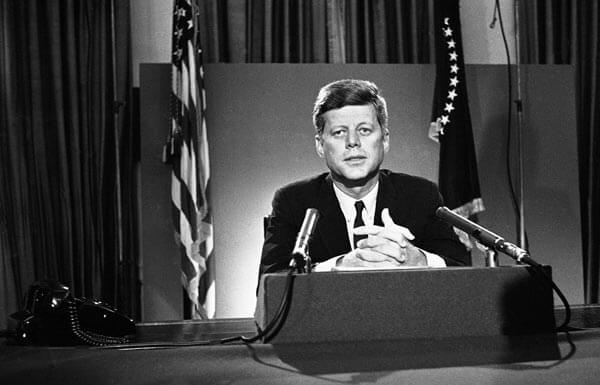

Dallas was the final stop for JFK in his mission to unite warring factions of the Texas Democratic Party, the conservatives headed by Democratic Gov. John Connally and the liberals who followed U.S. Sen. Ralph Yarborough (D-Texas).

Looking at the Dallas Morning News the morning of Nov. 22, 1963, the reader confronted a full-page ad with police mug-style photos of President John Kennedy and the headline: “Wanted for Treason.”

The atmosphere of right-wing conservatism appeared widespread. A Dallas barbershop might or might not have Life, Newsweek or National Geographic among its reading material for men awaiting a haircut. But barbershops were almost sure to offer books, tracts and pamphlets by right-wing authors such as W. Cleon Skousen or interviews and opinions by multimillionaire H.L. Hunt.

Johnson spat on

Vice Presidential candidate Lyndon Johnson and his wife, Lady Bird, were surrounded and spat on by a hostile crowd of mostly well-dressed women in downtown Dallas at the time of the 1960 presidential election campaign.

“LBJ Sold Out To the Yankee Socialists,” proclaimed a picket sign the attackers carried, referring to Johnson’s decision to run on the ticket with Kennedy.

The opposition to Kennedy intensified not long after JFK’s inauguration with the Dallas Morning News, headed by publisher E.M. “Ted” Dealey, printing a steady drumbeat of criticism of the young president.

Kennedy invited Texas publishers and top editors to an Oct. 27, 1961 luncheon at the White House at which Dealey told Kennedy “the general grassroots thinking in this country is that you and your administration are weak sisters. Particularly this is true in Texas right now.

“We need a man on horseback to lead this nation and many people in Texas and the Southwest think that you are riding Caroline’s tricycle.”

Some of the other publishers at the luncheon assured Kennedy that Dealey was not speaking for them.

Only a month earlier on Oct. 24, angry demonstrators disrupted a speech by United Nations Ambassador Adlai Stevenson in Dallas. A woman demonstrator struck Stevenson on the head with a picket sign. Frank McGehee, founder of the ultraconservative National Indignation Convention, was dragged out of the meeting of the Dallas U.N. organization by police when he used a bullhorn to try to drown out Stevenson.

Indignation convention

McGehee had formed the indignation group after he reported seeing what he said were Yugoslav pilots undergoing training at Perrin Air Force Base outside Sherman, Texas.

Big signs with messages that included “Join the John Birch Society and Save Our Republic,” “Get U.S. Out of U.N. Get U.N. Out of U.S.” and “Impeach Earl Warren” festooned some streets and highways in Dallas.

McGehee announced a three-night National Indignation Convention forum in Dallas in 1961 and I was assigned to cover it for United Press International as a reporter in the wire service’s Dallas bureau. Several newspaper chains as well as individual papers had sent telegrams to UPI and the Associated Press requesting coverage for morning and afternoon newspapers.

The program presented conservative speakers of many stripes, including those opposing big government, fluoride in the drinking water to prevent tooth decay, the United Nations, the federal income tax and Medicare, to list only a few of the many causes.

J. Evets Hailey, a West Texas cattleman, author and historian, addressed the indignation convention by calling for the execution of Earl Warren, chief justice of the United States.

H.L. Hunt

H.L. Hunt campaigned against Medicare, proclaiming it would “literally make the president of the United States a medical czar with potential life or death power over every man, woman and child in the country.”

In that highly charged political climate, many customers of the Nieman-Marcus luxury department store canceled charge cards in anger over President Stanley Marcus’ support of the United Nations.

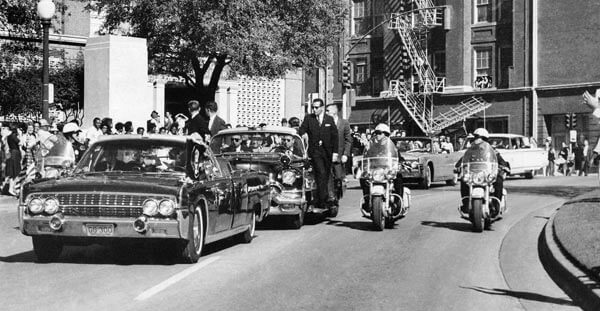

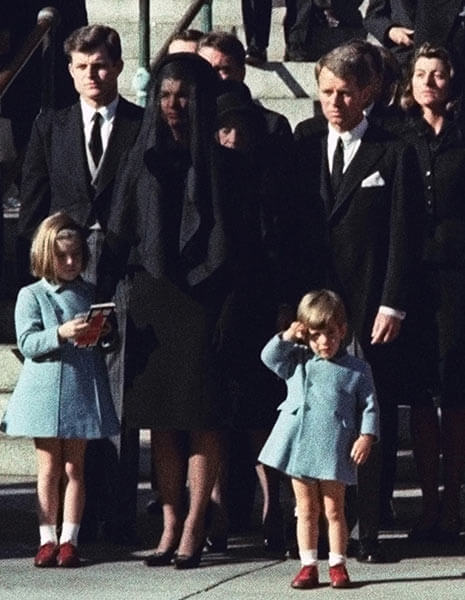

When the day came for Kennedy’s visit, however, crowds on the 11-mile presidential motorcade route appeared delighted by the glamorous president and the first lady. There were an estimated 150,000 to 200,000 spectators, surpassing most expectations. JFK even ordered his limousine to stop where children had lined up.

Gary Mack, curator of the Sixth Floor Museum in the Texas Schoolbook Depository, where Lee Harvey Oswald fired at the presidential motorcade, said years later, “When you look at films and pictures, you can’t find more than one or two negative signs — really nothing but smiles and cheers.”

Nellie Connally, the Texas governor’s wife, remarked to Kennedy as the two couples rode in the presidential limousine before the shots rang out, “Mr. President, you can’t say Dallas doesn’t love you.”

As I was leaving for work that sunny Friday, I turned on my car radio, which reported “possible gunfire” on the president’s parade route.

“Probably a false alarm,” I thought, but I abandoned my plan to do some errands en route and headed straight to the UPI bureau in a two-story former house in a scruffy neighborhood on Dallas’ west side.

My job at the UPI Southwest Division headquarters was heading the gathering and reporting of news from nine states for morning newspapers and other clients.

UPI vs. AP

In those years UPI and the Associated Press were on the front lines of news coverage. The two journalistic giants, both based in New York, served thousands of newspaper, television and radio clients from their far-flung bureaus around the world and were locked in intense competition on every major story.

I walked into the newsroom filled with clattering typewriters and Teletype machines just at the tail end of a journalistic drama involving reporters and editors scarcely able to believe what they were reporting to the world: the assassination of President John F. Kennedy.

Merriman Smith, UPI’s White House correspondent, had just telephoned the UPI Dallas bureau on a radio telephone — it was before cell phones or portable computers — in the press car in the JFK motorcade, dictating as the car following the president’s limousine at perilous speed toward Parkland Hospital.

When the phone rang at the news desk, our youngest reporter, Wilborn Hampton, who later joined The New York Times, picked it up and became the first one in the bureau to hear that Kennedy’s car had come under gunfire.

Merriman Smith’s advisory was typed onto the 60-words-per-minute Teletype circuit by Jim Tolbert, an unflappable operator, who transmitted the first report that the president had been shot to the world.

12:34 p.m. CST:

UPI A7N DA

Precede Kennedy

Dallas, Nov. 22 (UPI) — Three shots were fired at President Kennedy’s motorcade today in downtown Dallas.

At that point the UPI’s Chicago bureau attempted to send news of a murder trial. UPI’s world headquarters in New York admonished Chicago and advised all UPI bureaus:

Bureaus: UPHOLD (stay off this wire) and told the Dallas bureau:

“DA (Dallas) It’s Yours.”

A few minutes later Dallas sent a Flash, accompanied by 10 bells, a seldom employed advisory to newspapers, radio and television editors that what follows would be news of supreme importance.

Flash 12:39 CST

Kennedy Wounded Perhaps Seriously, Perhaps fatally by assassin’s bullet.

Finally, at 1:33 P.M. CST, official confirmation came that the president was dead. It was issued a few minutes after Smith’s telephone call to UPI reporting the death.

Newsroom at work

Taking all this information and turning it into trenchant news copy was Jack Fallon, UPI Southwest Division news editor. Fallon was a superb writer and among the last of what newspaper people called a rewrite man. As UPI staff members on the right and left kept feeding him notes phoned in by reporters outside the bureau, he blended them into the stories destined for media outlets across the globe, all the while typing at breakneck speed on a manual typewriter, using only two forefingers. A copy reader used a thick, black pencil to correct occasional strikeovers and missing letters before the copy was handed to the teletype operator.

Since we always had clients on deadline somewhere in the world, time was of the essence and thus UPI’s motto for its staff was “Get it first but first get it right.”

After UPI broke the news first that Kennedy had been shot, the archrival Associated Press was silent.

Merriman Smith never mentioned to UPI staffers in Dallas that while he was on the radio phone in the limousine, Jack Bell, his counterpart at the Associated Press sitting behind him in the press car, was pounding on his back, then his head, while loudly demanding that Smith give up the phone.

Smith held off Bell, telling him he had to ask staff members at UPI to repeat his dictation back to him because it was difficult for them to hear him, a subterfuge that prolonged the AP’s tardiness in reporting a monumental news story.

The staff in the Dallas bureau scrambled to cover news conferences at police headquarters and other spots to pull together the pieces of the developing story. For example, I was assigned to visit the home of Ruth Paine, a Quaker who was a friend of Oswald’s wife, Marina. Newsmen — there were no women in Dallas although some other bureaus had women staffers — were busy getting assassination sidebars over the phone.

Foreign reporters

By Sunday morning, reporters from many foreign countries started arriving. It was our job to supply them with telephone numbers, directions and the use of our facilities.

One such reporter walked into the UPI around 4 a.m. Sunday and said he was from Corriere Della Sera in Milan. The Italian newspaper in those days was UPI’s biggest consumer of foreign news.

“Where do you come from?” I asked.

“Bamako,” he said, referring to the capital of the African nation of Mali.

He had been covering a meeting of the Organization of African Unity.

“My office told me, ‘Go to Dallas.’”

Felix McKnight editor-in-chief of the Dallas Times-Herald, estimated that at one point there were around 800 journalists from out of town.

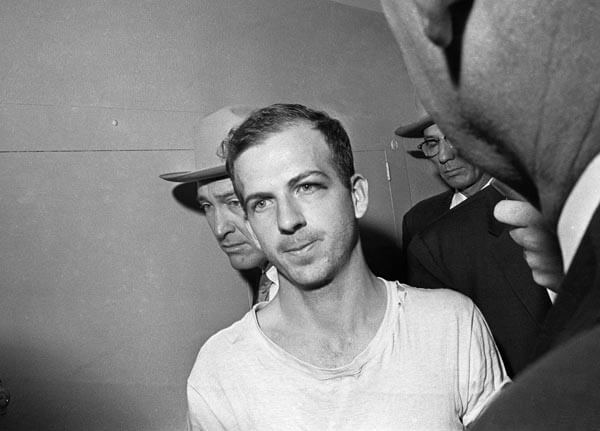

One of UPI’s Dallas staffers, Curtis Gans, seemed perpetually on the phone. He was in search of information on Lee Harvey Oswald. It seemed possible that at one point, few people knew more about Oswald.

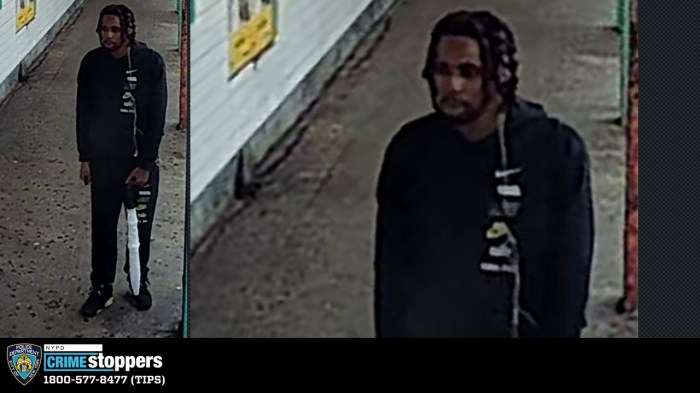

On Sunday, I was sent to the Dallas County Jail, awaiting Oswald’s transfer. The jail’s facilities were more secure and modern than the police headquarters lockup, where Oswald had been held since his capture in the Texas movie theater in the Oak Cliff section of Dallas. Oswald had been questioned extensively, always denying he was the assassin. To repeated questions of whether he was a Communist, he said he might have been a Marxist at some level.

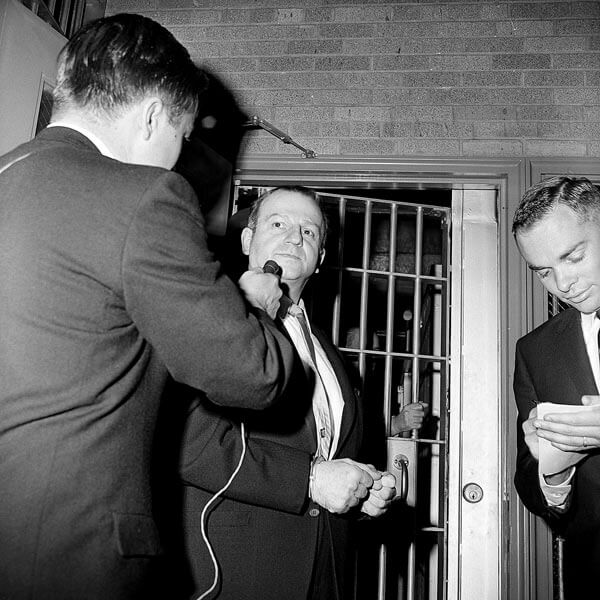

Close to 100 reporters and cameramen were waiting at the county jail and we were all able to hear clearly on a radio-telephone loudspeaker what was going on at the police headquarters as Oswald was readied for the trip of less than a mile.

Oswald shot

Suddenly we heard a blast from Dallas strip club owner Jack Ruby’s pistol followed by bursts of profanity from his police escorts, including “Jack, you son of a bitch!”

We ran for our cars, headed for Parkland Hospital where not long after we were told that Oswald, too, had died of a gunshot wound.

UPI staffers Mike Rabun and Terrence McGarry were only feet from where Oswald was shot.

“Several of us dived behind pillars, not sure but what there were more gunmen,” Rabun recalled recently.

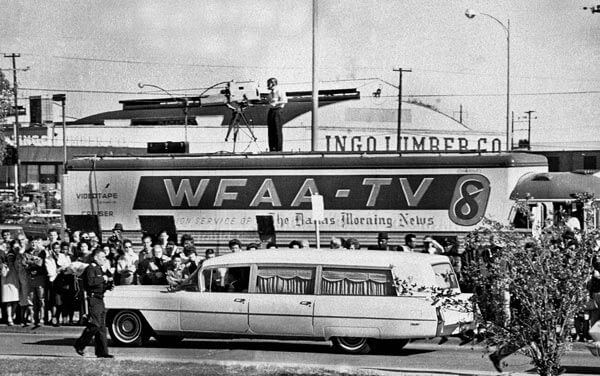

Three days later UPI’s Dallas bureau manager, Preston McGraw covered Oswald’s funeral and was pressed into service as a pallbearer as were several reporters from other news organizations because attendance was so sparse at the rites in Fort Worth, 32 miles west.

Epilogue

White House correspondent Merriman Smith was a symbol of the minute-by-minute battle between UPI and the Associated Press to get the story first. This rivalry played out from the smallest statehouse bureau in North Dakota to remote outposts in African. UPI’s headquarters in New York kept a daily score of which newspapers printed UPI stories and which used the AP versions. Losing to AP was embarrassing and, if it happened repeatedly, might mean trouble for that staffer.

As the press car arrived at Parkland Hospital, where Kennedy and the wounded Connolly had just been taken, Smith tossed the radio phone he had commandeered to the AP’s Bell, but it went dead.

Smith’s first mention of the pounding he took from Bell over the radio phone in the car was at the Washington Press club the same night Kennedy was assassinated. “Smitty,” as he was known, flew back to the capital aboard the plane taking the newly sworn-in President Johnson and Kennedy’s body to Washington. He proudly displayed his black and blue back to fellow reporters as a visible sign of his triumph over the opposing White House correspondent.

Smith, who turned 50 that fateful day, won the Pulitzer Prize for National Reporting for his coverage of the Kennedy assassination.

Reach contributing writer Philip Newman by e-mail at timesledgernews@cnglocal.com or phone at 718-260-4536.