BY YOAV GONEN, THE CITY

This article was originally published on by THE CITY

Athanasia Zapantis was at her job as a home health aid on the evening of Father’s Day when her 29-year-old son called in a panic.

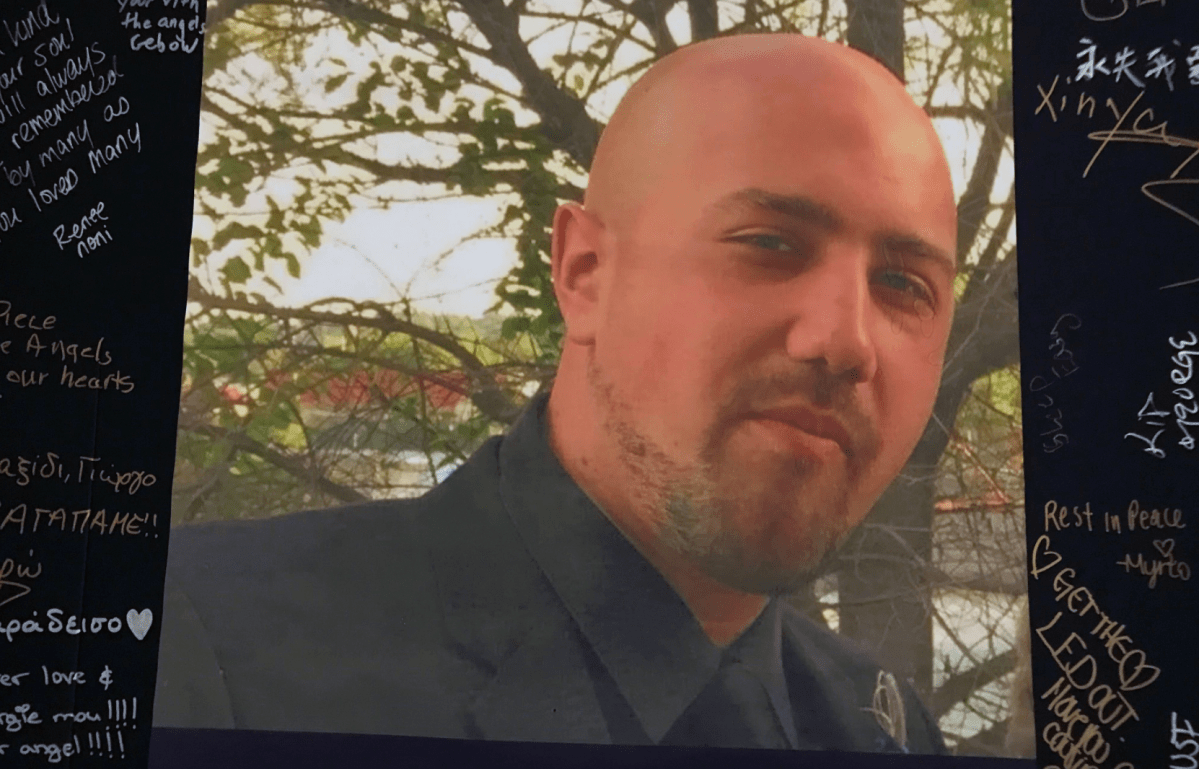

George Zapantis, described by family members and neighbors as a gentle giant with mental health issues, was alone at their Queens home and alarmed by the sudden arrival of police officers.

“He said, ‘Mommy, I see the cops outside. I don’t know why,’” said Athanasia Zapantis, a 52-year-old native of Greece. “He said, ‘Mommy, come home. Mommy, come home.’”

A short time later, cops tased him at least three times just outside the entrance to his two-family home in Whitestone, neighbors said. He fell unconscious, according to fire officials, and was transferred to NewYork-Presbyterian Queens Hospital where police said he was pronounced dead of an apparent heart attack.

The NYPD has publicly said that officers deployed their Tasers after Zapantis approached them holding what they described as a samurai sword.

But three weeks after her son’s death, Athanasia Zapantis said she’s been given no information directly by the NYPD or City Hall about exactly what happened that night.

She wants to know why police didn’t listen to neighbors — who said they told cops multiple times that Zapantis had mental health challenges and that they should wait for his mom to arrive.

She wants to know why cops haven’t released body camera footage of the June 21 incident outside her 150th Street home.

And she wants to know why, as a video filmed by an upstairs neighbor depicts, cops continued to tase her apparently then-weaponless son — leading him to cry, “Help, help!”

“I’m a mother,” Athanasia Zapantis said. “I want to know what happened to my son.”

Multiple probes launched

The family’s attorney, George Vomvolakis, said the NYPD has refused to provide him with body camera footage from the officers who responded — even as the department released footage within hours of another forceful arrest that day elsewhere in Queens.

Just four days before Zapantis’ death, Mayor Bill de Blasio announced a series of reforms to the NYPD disciplinary process he said would provide the improved transparency and accountability advocates sought.

Body camera footage from serious incidents — including shootings or tasings by police — would now be publicly released within 30 days, the mayor said.

Investigations by the NYPD’s Internal Affairs Bureau of encounters where civilians suffer “substantial” injuries would now be required to be completed within two weeks, de Blasio announced that day.

“People deserve to know that if an officer has done something wrong … that the decision about whether there will be further disciplinary action happens in a meaningful time frame,” the mayor said of the new two-week time limit on June 17. “This is what we need to do everywhere to show people there will be real accountability.”

On Saturday, NYPD officials said the incident was still under investigation by the department’s Force Investigation Division, which was established in July 2015 in response to the choking death of Eric Garner on Staten Island a year prior.

The state Attorney General’s Office confirmed it’s also investigating the incident under a state special prosecutor power for cases of police killings of unarmed civilians — or in cases where there are questions about whether the civilian was armed and dangerous at the time. A spokesperson for Attorney General Letitia James said the NYPD is free to investigate simultaneously.

Vomvolakis said the city’s three weeks of silence about the case has been especially painful for Athanasia Zapantis as she cares for her 33-year-old daughter, Eleftheria, who has Rett Syndrome.

“I want to speak to the mayor,” Athanasia Zapantis said.

History of mental illness

George Zapantis grew up largely without his father, who also died at the age of 29, in 1993.

He would often take care of his sister, buy presents for his nieces and nephews, and surprise his mom with flowers, according to his cousin, Marina Zapantis.

His most recent job was in security — his last check, for $1,300, arrived shortly after he died — and he previously worked in construction and in the restaurant industry, his cousin said.

“He was a very sweet boy. He did battle with his mental health issues from his late teenage years on,” said Marina Zapantis, an attorney who lives in Astoria. “But he was able to hold down a job and had friends and stuff like that.”

In recent years, George Zapantis was on and off medication used to treat bipolar disorder and other mental health issues, according to his mother.

She said she tried seeking help from mobile mental health teams that are run by hospitals and by the city — but that both times the responders ignored her instructions not to tell Zapantis she had called them. He refused treatment, she said.

George Zapantis himself called 911 twice in recent years, once based on a dream he had and later out of concern for the medication his mother was trying to give him, she said.

The first time, he was hospitalized for about two weeks at North Shore University Hospital in nearby Manhasset, L.I. — his mother said she had wanted him treated for longer — and the second time he was in and out of Flushing Hospital within a day, she said.

Vomvolakis said the cops who came to the house on June 21 weren’t from the specialized unit that handles people in mental crisis, called “emotionally disturbed persons,” or EDPs, in police parlance.

“The police … knew or should have known that when they were responding, it was going to be what they call an EDP,” he said. “They should have sent a different team than regular patrol officers — who were ill-equipped and -prepared to encounter someone with mental illness.”

Under ThriveNYC, a billion-dollar mental health initiative launched in 2015 by Chirlane McCray, the mayor’s wife, the city bulked up the mobile crisis program that treats people with mental health challenges using traveling teams of health professionals.

Despite a commitment in October 2019 to extend the program to respond to some 911 calls that involve mental crises — something advocates have pushed for as 16 people with mental health challenges have died at the hands of police since 2015 — that emergency response program is still on hold.

ThriveNYC officials told THE CITY a pilot plan in two precincts for joint responses to 911 calls by police and mental health professionals had been postponed because of the coronavirus crisis. The officials said they don’t have a new timeline for launch.

Sparked by a floodlight

The June 21 incident started with a dispute between George Zapantis and the family upstairs, who normally enjoyed a good relationship with him, over a backyard floodlight.

Zapantis turned it on. Ricky Noble, the upstairs neighbor, turned it off.

The Nobles learned only afterward that Zapantis had wanted the bright lights on because he was scared of a next-door neighbor, who, his mother said, often harassed them.

When Zapantis turned the floodlight on again, Noble’s 25-year-old son went down to speak with him — and returned to tell his parents that Zapantis had answered the door holding a sword.

Ricky Noble described the blade as something out of the movie “300,” but said none of the family members felt threatened.

“It was in a case. He just had it with him,” he said.

His wife, Shaniqua Noble, went downstairs to talk with Zapantis. When they resolved their argument, Zapantis closed the door to his apartment and she walked to the front yard to speak to police, who arrived just before 9:30 p.m., according to the NYPD.

A neighbor who was walking his dog had called 911 to report a person with a gun and had mentioned the Nobles’ vehicle, Ricky and Shaniqua Noble said cops told them. The NYPD told THE CITY that the call was for a man with a gun inside the residence, but declined to provide audio or a transcript of the call.

“I explained to the cops that George was mentally challenged — so did my husband and my son,” said Shaniqua Noble. “I explained the whole situation. I explained to them we were waiting for his mother to come back.”

Ricky Noble confirmed he also told police about Zapantis’ mental illness.

“George is panicking and they’re shining the flashlights through the windows and yelling his name,” said Ricky Noble.

“I was outside with them saying, ‘He takes medication. He’s not all there.’ I said, ‘Just wait for his mom’ — and they just refused.”

‘Call the cops!’

Around the time the mother and son spoke for the last time by phone, Shaniqua Noble could hear the police approaching the door to the Zapantis home.

“They went to knock on the door. He knocked on the door in response,” said Shaniqua Noble.

Marina Zapantis, who said her cousin was like a younger brother to her, managed to reach him by phone.

“He told me, ‘Marina, call the cops! The cops are at my door. Marina, calls the cops!’” she said. “That signaled to me he was confused or didn’t really know what was going on.”

Within minutes, the cousins connected again by phone.

“I heard him tell whomever was there, ‘I have the right to protect myself,’” she said. “It sounded like it was silent. I heard him clearly, so I’m sure things escalated after that point.”

Ricky Noble said the encounter turned physical only after Zapantis finally obeyed the police officers’ commands to open the door.

“He cracked open the door to speak to them and they broke the screen door to grab him,” said Ricky Noble, adding he saw officers tussling with Zapantis from the end of the walkway, near the backyard.

Detective Sophia Mason, an NYPD spokesperson, said in a statement that officers found Zapantis in his apartment “holding a samurai sword and refusing to comply with the officers’ directives and orders.”

She said he began to “engage the officers and approach them with sword in hand,” but the statement makes no mention of any overt threats.

Mason said the officers deployed their Tasers and that Zapantis was “subdued,” but that he suffered a “medical condition/cardiac arrest.”

Fire Department officials said they got a call at 9:44 p.m. about an unconscious patient at the Zapantis home. They said two police officers were also injured and transported to a nearby hospital.

A spokesperson for the city medical examiner’s officer said early Sunday that a cause of death has yet to be determined.

Captured on video

A series of videos shot by the Nobles’ 16-year-old daughter, Shakira, shows a chaotic encounter between Zapantis and at least five police officers in a narrow walkway outside the doorway to the home.

Through much of it, Zapantis has his back toward the officers and his hands behind his back, but he also fails to comply with their demands.

“Get on the ground now!” shouts one police officer. Another shouts, “Get down!

A few seconds later, another officer says, “You’re going to get Tasered again if you don’t get down!”

A male voice shouts, “Hit him again!” — followed closely by a zapping sound.

Zapantis screams and curses. “Help, help!” he says.

Moments later, Zapantis can be seen standing upright with his back toward the officers, with his hands behind his back.

“Put your hands behind your back and stop,” one officer says at the end of the clip.

Ricky Noble said police tased Zapantis again after that.

“At the end, they tased him one more time to put him on the floor — ‘cause he wasn’t going on the floor,” said Noble. “He went down hard.”

NYPD officials wouldn’t say how many times officers deployed their Tasers, nor would they identify the officers involved.

They didn’t answer additional questions about the incident and the force division’s investigation.

Athanasia Zapantis said detectives met her at work that night after telling her that her son was in the hospital. She said they spoke to her for 90 minutes and at one point broke the news that her son had died.

She screamed.

Use of force rules

The NYPD’s guidelines for using Tasers say the devices should be used only against people who are “actively resisting, exhibiting active aggression, or to prevent individuals from physically injuring themselves or other[s].”

Factors to be taken into consideration include the “immediacy of the perceived threat,” and the number of civilians involved compared to the number of officers.

Vomvolakis said neither the family members nor the neighbors know what happened between the time Zapantis apparently opened the door and the beginning of the Nobles’ video.

“I do know that he did have some kind of sword. Whether he was brandishing it when the police arrived or when they were communicating through the door, I have no idea,” he said. “The body cam should show that clearly.”

But the Nobles said their video shows that, even if an initial tasing was justified, subsequent use of the device came when Zapantis didn’t appear to be a threat.

“You’re seeing him outside the home without the sword. Both his hands were behind his back,” said Ricky Noble.

In a December 2019 report, the watchdog Civilian Complaint Review Board found that among 114 allegations of Taser misuse between 2014 and 2017, the police followed proper procedures for using the devices more than two-thirds of the time.

The board substantiated 10 allegations of misconduct — 9 percent of cases — while the remainder of complaints were either unfounded or unsubstantiated.

But the review also found that a significant percentage of those tased were people going through mental health crises — 37 percent of cases in 2015, and 67 percent in 2016.

Athanasia Zapantis acknowledges she doesn’t know what led up to the first instance in which the police tased her son.

But, she adds, “They had no business to do the second and third time, the Taser.”

‘I need answers’

Several days after her son’s death, Athanasia Zapantis found his slippers near a spot of blood inside the entrance of the home.

Until then, the NYPD had barred her from coming inside — presumably because of their investigation, her lawyer said.

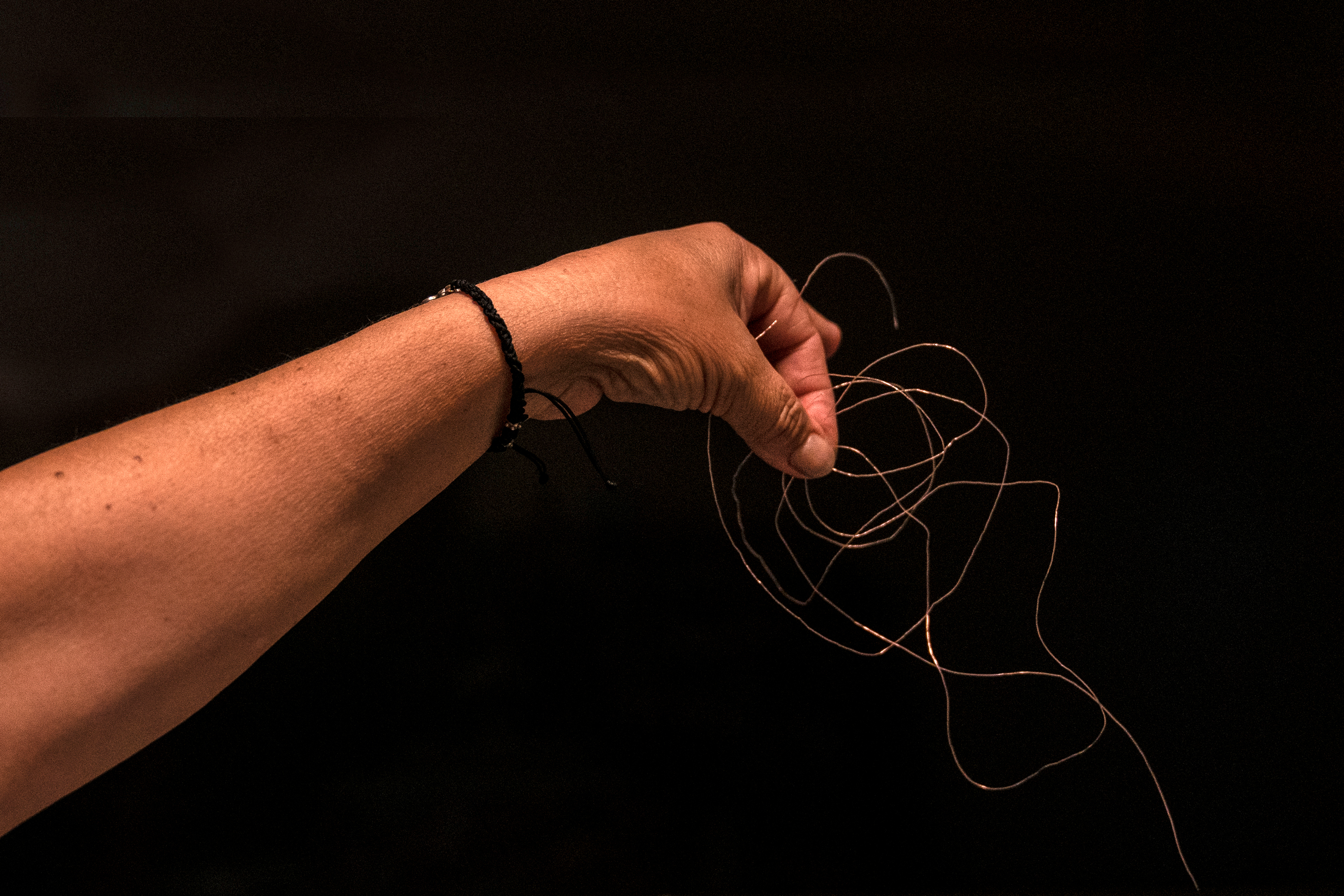

Zapantis also found the leftovers of the chopped meat with pasta she had cooked for her son on Father’s Day before leaving for work. She collected a short remnant of a Taser wire from just inside the home, and a longer wire stuck inside the damaged, outer screen door.

She placed both wire fragments in a plastic bag.

Even after her son’s death, Athanasia Zapantis periodically peers into the front yard through the blinds of her kitchen window.

It’s a habit of checking to see if her son is coming home from work.

“I need answers,” she said. “I need answers soon.”

THE CITY is an independent, nonprofit news outlet dedicated to hard-hitting reporting that serves the people of New York.