This article was originally published on by THE CITY. Sign up here to get the latest stories from THE CITY delivered to you each morning.

Last April, Thomas Earl Braunson III was found dead in his cell on Rikers Island. The 35-year-old had struggled with addiction throughout his life, family said, and in the end that battle proved fatal.

Braunson, who had become a father just three months earlier, succumbed to a deadly dose of fentanyl, heroin, and PCP, according to the city Medical Examiner.

Department of Correction investigators are still trying to determine how that contraband got to Braunson behind bars. But his access to drugs was hardly an outlier during the height of New York City’s pandemic when social programs were shut down and visitors were not allowed on the island.

In fact, internal jails numbers suggest that in that period — when only corrections officers, staff, and eventually certain contractors and service providers could enter — detainees may have had even greater access to drugs.

Between April of 2020 and May of 2021, correction department authorities seized banned drugs inside city jails more than 2,600 times, according to data obtained by THE CITY.

That’s more than double the number of such seizures made during the same time period from 2018 to 2019 when the jail population was larger and there were more people coming and going, Correction department records show.

Pointing Fingers

For criminal justice reform advocates, the statistics point to a longstanding accusation.

“This data confirms what we’ve known all along — it is corrupt DOC staff who keep drugs flowing into Rikers,” said Darren Mack, co-director of Freedom Agenda, a jail reform organization. “But instead of swift action to root out this corruption, we’ve seen investigators fired, and discipline that is either absent or takes years to enact.”

The Department of Correction disputed those allegations, with a spokesperson arguing that the agency takes contraband smuggling “extremely seriously.” The DOC rather blames the spike on a “dangerous increase in attempts to get drugs through the mail” during that period of the pandemic.

The data does show an increase in drug mail seizures during that period, but they account for less than a third of total drug recoveries between April 2020 and May 2021.

In response to a follow-up inquiry noting that mail recoveries could not account for a majority of the surge, the department pointed out there will always be some contraband “that slips through.”

Jail officials throughout the country have for years struggled to block the smuggling of books and magazine paper soaked in suboxone, K2 and meth.

Benny Boscio, president of the Correction Officers’ Benevolent Association, accused reform advocates of “promoting false narratives” about his union’s members.

“Anyone who falsely claims that Correction Officers, who enter and exit the jails via body scanners every day, are responsible for the majority of the drugs recovered in our jails must be on drugs themselves,” Boscio said. “Simply because drugs were recovered while there were less inmate visits in a certain time frame doesn’t mean contraband wasn’t already brought in by visitors before the visits stopped.”

Mack, who was previously incarcerated on Rikers Island himself, disputed the union’s assertion that recently seized contraband had been circulating inside for months, perhaps years, calling the idea “frivolous.”

“If you’re a seller, you’re going to sell as soon as possible because of the dangers of being searched and caught with it,” he said. “People who have been incarcerated know that drugs go as soon as they hit the market.”

Less Correction

The troubling numbers come as early moves by the Adams’ administration signal a more hands-off approach to staff misconduct in city jails.

He replaced reform-minded Correction Commissioner Vincent Schiraldi with Louis Molina, a former NYPD detective who had been serving as chief of the Las Vegas Department of Public Safety.

As one of his first big moves, Molina replaced Sarena Townsend, the department’s acclaimed top investigator. Townsend, a former Brooklyn prosecutor, told the Daily News Molina had asked her to clear 1,000 disciplinary cases against officers over the next 100 days before she was ordered to resign.

The city jail system has been roiled by what a federal monitor calls “disorder and chaos,” with inmate deaths and self-harm incidents up, rampant absenteeism and low vaccination rates among officers, and bleak conditions at intake centers.

Ben Fractenberg/THE CITY

Ben Fractenberg/THE CITYSome elected officials have called for the National Guard and President Joe Biden to step in.

Braunson and 15 other city jails detainees died behind bars in 2021, the highest total in years.

At least one other case was tied to a drug overdose, according to the medical examiner’s office.

Jose Mejia Martinez, 35, in jail on a parole violation for allegedly stealing beer, was found dead inside his cell in Rikers Island’s George Motchan Detention on June 10, 2021.

He died from “acute methadone intoxication,” the medical examiner’s office concluded.

‘They Had a Monopoly’

The Department of Correction data shows that drug seizures remained relatively stable between 2018 and early 2020, averaging about 77 a month, excluding those recovered through searches of visitors and mail.

In April of 2020, the first full month of the pandemic lockdown, such seizures dropped dramatically. But as jail programming and visits ceased, fueling despair and violence, drug recoveries reached new heights with 334 in October of 2020 and 570 in February of 2021.

Brian Carmichael, an incarceration reform activist who spent time on Rikers Island last spring for a narcotics charge, said it is an “open secret” that some corrections officers sell drugs to detainees, but the pandemic presented a special opportunity.

“There are only a few ways that drugs can get into a jail, so when visits were canceled for COVID, that effectively eliminated any competition there was for those guards bringing in the drugs,” he said. “And they had a monopoly.”

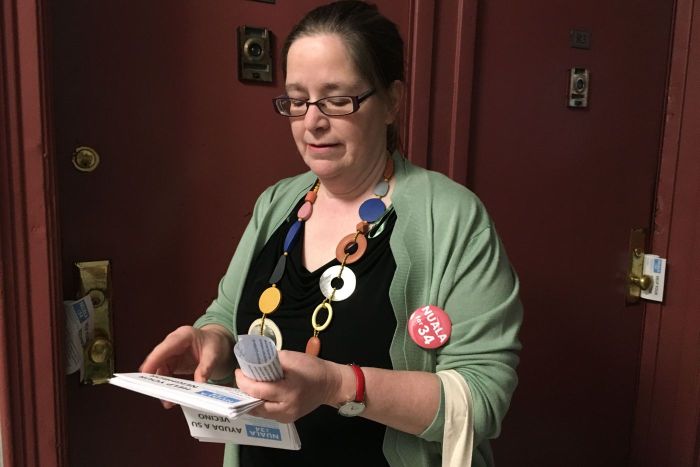

John Proctor

John ProctorDrugs were in high demand when he arrived, Carmichael said. In those months, corrections administrators were struggling to get hundreds of corrections officers to show up to work, stranding detainees who were unable to get escorts for medical visits.

“If people can’t get psych meds and pain meds, then they’re going to turn to whatever meds they can find,” he said. “Whether it’s pot or K2, heroin, meth, anything you can get.”

Nearly half of all incarcerated people in New York City are deemed as having some symptoms of mental illness, according to DOC data compiled by the Vera Institute of Justice.

Under Pressure

City investigators have long been concerned about corruption within the correctional ranks. But experts say the particular chaos that the jail system went through during the pandemic may have exacerbated both opportunities for and interest in breaking the rules.

Schiraldi, who served as DOC commissioner from last May to December, said he believes the overwhelming majority of corrections officers attempted to do their jobs honestly during the pandemic. But in that period of crisis, some lost sight of their mission.

“When morale declines people do things that are outside of their normal moral code — they call out sick when they’re not sick, they AWOL, they bring in contraband,” he said.

The New York City jail system is not alone when it comes to a contraband spike during the pandemic.

Ben Fractenberg/THE CITY

Ben Fractenberg/THE CITY

The Texas prison system also stopped visits and limited mail but the guards found as many drugs and wrote up more detainees for that violation, the Marshall Project reported.

In a January sentencing memo, Darrel Diaz, a Rikers officer who was caught by city investigators for smuggling in a cell phone, cigarettes, and paper soaked in the drug K2, argued that the daily violence that plagues the island caused him to start smuggling in March 2020.

“The reality at Rikers, where the inmates overwhelmingly outnumber the guards, is that the gangs control every aspect of life on the units,” his attorney wrote in the court document. “If there were fights, stabbings, and other disturbances in the unit, Diaz would not get approved for full time employment at the jail, a position he was eager to secure.”

THE CITY is an independent, nonprofit news outlet dedicated to hard-hitting reporting that serves the people of New York.