On March 14, 2025, eight police officers arrived at Malba resident Kristy Kiely’s home on a false report that it was an “operational drug den” filed by her former partner and co-parent, Robert Weisenburger. The incident led to a months-long custody battle between the two over their 14-year-old daughter, which Kiely is still fighting in the legal system today.

Kiely and a representative allege that the response to the false report was in stark contrast to the 109th Precinct’s reaction to the violent Malba street racing incident that occurred on Nov. 23, in which police failed to arrive on the scene for around 40 minutes, all because the father’s brother, Officer Edward Weisenburger, is a member of the force himself.

Officers arrived at Kiely’s home within minutes of the false report, a practice known as “swatting.” At the time, police stated the report had credibility, but found no drugs or evidence of criminal activity after searching the home, and no charges were filed. Despite that, the incident and other reports made by the father triggered Queens County Family Court to remove Kiely’s daughter from her home during the investigation and she hasn’t been allowed visitation since that day, forcing her to file an official complaint and question why the false flag was taken more seriously than other reports, such as those on the street racers later that year.

“The lie brought an instant response,” Kiely said. “The truth came too late — and it cost me my child.”

The week of Thanksgiving, dozens of individuals raced through the residential streets of Malba, doing donuts and disturbing the peace in the quiet neighborhood, and eventually even burning one resident’s car with fireworks and assaulting a couple who confronted the group on the front lawn of their home. The clash sparked controversy towards the NYPD and led to a mass community pushback against their handling of this case and other car meet-ups in the area, which have become a common occurrence in Northeast Queens since the COVID-19 pandemic due to the area’s wider roads and lack of late-night traffic.

“What happened in Malba was unreal, but it’s the same chaos we see across the city”, said then Council Member Robert Holden. “Punks take over our streets while the cops do nothing.”

Malba’s representative, Council Member Vicky Paladino, echoed Holden’s sentiment, calling the situation “insane,” admonishing the slow response time and vowing to crack down by installing speed bumps and other infrastructure to deter other street racers in the future.

According to several Malba residents who called 911, the severity of the incident was misinterpreted and reported as a simple noise complaint to 311, resulting in a delayed response. However, an NYPD spokesperson stated the 109th Precinct officers were simply busy with other calls during the early Sunday morning hours, and later appointed four more patrol cars dedicated specifically to Malba. So far, one man has been arrested and charged with assault.

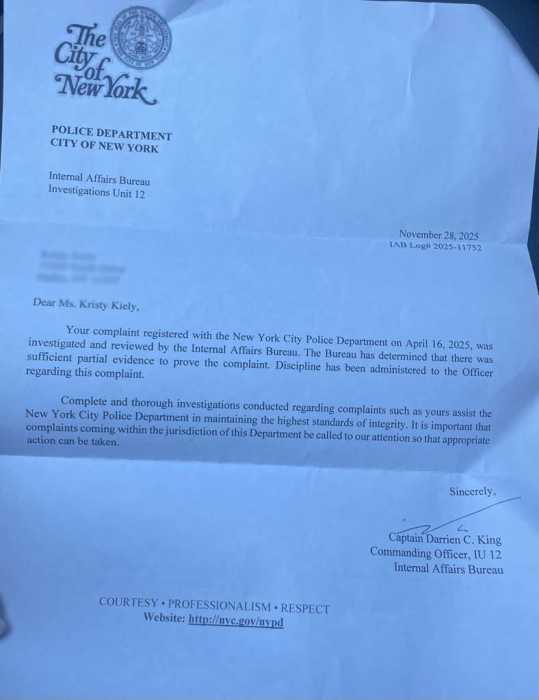

Kiely cites the lack of urgency as an example of the NYPD’s priorities in Malba, with advocates and politicians requesting that the neighborhood, Whitestone and College Point be given their own precinct, as the 109th Precinct dedicates most of its resources to Flushing. Kiely had complained after the swatting incident and, shortly after the Malba riot that saw a much lighter police response than her own case, received a letter from the Internal Affairs Bureau (IAB) stating her complaint against the precinct and her daughter’s uncle had “sufficient partial evidence” of adverse actions towards her and a “command discipline” had been administered. A command discipline could mean the loss of up to 10 vacation days, depending on its schedule, as well as oral admonishment.

Kiely’s former partner had filed another claim that year that the mother had gotten her child intoxicated while out to dinner in early February. The case was later closed and no wrongdoing was found. The Court, received yet another complaint from the father in May, despite the fact that Kiely had not had custody of their child since the March 14 swatting incident. Earlier that month, Weisenburger was charged with custodial interference, child endangerment and criminal contempt of court for violating court-ordered visitations on 32 separate occasions, though the charges were later dropped in June.

Attorney for the Child Austin I. Idehen stated on the record that Kiely had used “every means necessary” to try to have the father arrested on what he characterized as “bogus charges,” despite NYPD confirmation that the allegations were closed and unfounded.

After the third complaint filed that year, Kiely’s visitation rights were completely suspended on May 19, while she remained unrepresented in Family Court, even though by law she was supposed to be appointed an attorney as a part of the Assigned Counsel Program, Article 18-B. Although she requested abeyance until they found her representation, the court still proceeded and transferred temporary custody without an evidentiary hearing to the father.

“I was treated like the defendant,” Kiely said. “The person violating court orders was protected, and my child was removed without proof.”

Kiely’s trial in Family Court, based on the several cases the NYPD has already closed, will begin in June of this year. Kiely’s experience has called her to question the repercussions of abusing emergency reporting and power imbalances in Family Court proceedings based on familial relationships in law enforcement. To this day, the mother is still critical of the NYPD’s prioritization of the initial claim that led to her loss of custody, in comparison to other incidents like the violent mob in Malba, as well as the transfer without proper hearings.

“Each delay keeps the separation going,” she said. “My daughter keeps growing up without me — even though police already cleared this.”