By Jeremy Walsh

Although Queens real estate is miles away from the Wall Street epicenter of the financial crisis gripping the city, half a year after the stock market collapsed the borough’s construction industry has been left reeling, builders and officials said.

Credit for developers has dried up since Lehman Brothers filed for bankruptcy in September, setting off a wave of panic selling on world markets that enveloped other investment banking houses, large commercial banks and institutions with major holdings in worthless subprime mortgages.

According to figures from the U.S. Census, Queens had 38 new residential housing permits for 121 units in February, compared with 72 permits and 257 units in February 2008, a decrease of 48 percent. For the first two months of the year, there were 56 new permits for 243 units filed in Queens, a drop of 61 percent from the 142 permits filed for 424 units during the same stretch of 2008.

By comparison, Brooklyn had eight new residential permits for 36 units in February compared with 44 permits and 278 units in February 2008, Census figures show. For the first two months of 2009, there were 14 permits filed for 83 units, down 84 percent compared to the 89 permits filed during the same stretch of 2008.

Joe Conley, chairman of Community Board 2, said the major building projects already under construction appeared to be proceeding as planned in booming areas like Long Island City, where 38 residential and commercial developments were under way around Hunters Point in 2008. The problem, he said, comes after the building goes up.

“The thing we have a concern about is the explosion we had in the construction in this area,” he said. “We don’t want to see a lot of these buildings empty.”

Flushing is another area jeopardized by the economic downturn. Muss Development’s Skyview Parc mixed−use development in downtown Flushing was designed to include 448 luxury apartments on top of a major retail complex. Though the $1 billion project ran into lending problems earlier this year, Muss officials said the first residential tower and the retail center are expected to open this summer.

Another major project in the area was Flushing Commons, a $500 million undertaking first introduced by the city Economic Development Corporation in 2005. City Councilman John Liu (D−Flushing) has said the proposal is dead in the water, however.

Lou Colletti, president of the Manhattan−based Construction Trades Council, did not have specific statistics for the borough, but said Queens probably would be more affected than other boroughs by the construction downturn because of the residential building surge of the past few years. Residential development projects not already in the pipeline have been hit particularly hard, he said.

“In many instances, I’ve had developers tell me loans they had been approved for are being taken back because the economics of the building don’t work anymore,” he said, noting he did not expect the construction market to bottom out until the third quarter of 2009. In 2008, banks expected a 10 percent equity investment or 10 percent down payment based on the economics of the project, Colletti said. These days financial companies are asking for 40 percent down payments, he said.

Vincent Riso, president of the major residential developer Briarwood Organization, said the company is having success selling its 130 affordable−housing condominiums at the Water’s Edge development in Arverne, partly because they include tax credits.

“Things are moving, but slowly,” he said. “But on a market−rate basis, there’s no funding from banks.”

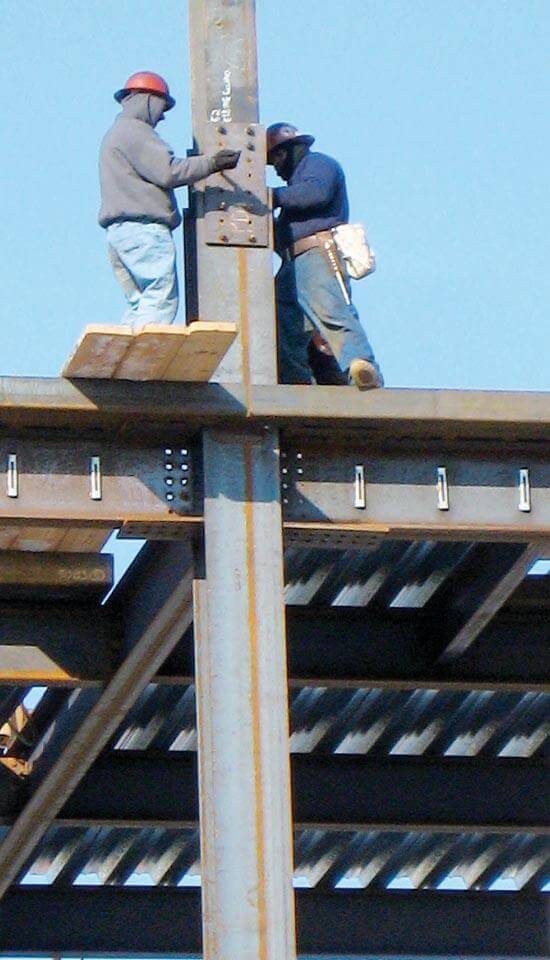

Construction workers in the borough are likely to be hurt. Colletti said he expected the citywide construction unemployment rate to approach 50 percent this year. Figures from the state Labor Department were only available through the second quarter of 2008. They showed the total number of construction jobs in Queens had climbed slightly to 46,347 from 44,628 in the same quarter of 2007.

But Elaine Tomasetti, co−owner of the Rockaways−based heavy construction company J&E Industries, said she has halved her number of employees since April 2008, from 41 to 19.

“Payroll is even less because there’s really no overtime in any of the work we are doing,” she said. “The work is very scarce. There’s a couple of foundations that I know of [where] the owner’s not even putting up the building anymore.”

She said she had no idea when business would pick up again, but was actively soliciting projects.

“I never really did that much,” she said. “It was usually continuity. You had clients you worked for and it was one job after the next. It’s not like that now.”

But another challenge facing developers is the city’s introduction of an online document filing system for building projects. The system allows for a 30−day public review process that enables any resident to challenge the submitted plan and get a response from the DOB. Riso worried it could put new construction projects on ice for six months or more.

“There should be a right to look at these things, but if the bank knows the public could hold me up for six months, they’re not going to provide financing,” he said. “You know how the public loves builders. We’re the bottom of the bottom.”

Reach reporter Jeremy Walsh by e−mail at jwalsh@timesledger.com or by phone at 718−229−0300, Ext. 154.