BY RASHED MIAN

U.S. Army veteran Chris Daniels survived three roadside bomb explosions during his two-year tour in Iraq, and aside from a wounded leg, the disorienting blasts left him relatively unscathed, physically.

Yet the war did not end for the Centerport resident once he traded the desert battlefield for the manicured lawns and promise of laid-back weekends in suburbia in November 2005.

“When you get home you’re still in hyper-sensitive mode as far as ready for combat,” Daniels, now 42, tells the Press. “So, it takes a couple of months to realize you’re actually home.”

His troubles began almost immediately after departing the Middle East: Every time Daniels shut his eyes, he’d be haunted by nightmares, as if his brain was deliberately protesting his attempts at sleep. At best, he’d manage four hours a night.

Ultimately, Daniels was diagnosed with Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder, or PTSD, a mental health condition often triggered by experiencing or witnessing a terrifying event—which growing research suggests those who’ve suffered even a mild brain injury, such as concussions among returning troops from Iraq and Afghanistan, or those plaguing longtime NFL players, are more susceptible of developing.

Although concussions—the most common traumatic brain injuries (TBIs)—are often associated with sports, statistically they’re attributed to more rudimentary origins, such as falls, which the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) ranks as their predominant cause, followed by unintentional blunt trauma and motor vehicle crashes.

An estimated 1.8 to 3.6 million traumatic brain injuries occur annually in the United States, reports the CDC, and TBIs account for 30 percent of all injury deaths each year. Diagnoses for concussions have increased 43 percent in the United States within the past five years, with a 71-percent spike among patients 10 to 19 years old, according to a recently published analysis by insurance giant Blue Cross Blue Shield.

Before his exposure to the horrors of war, Daniels spent his teenage years playing football and lacrosse, both contact sports. When he was a young athlete, head injuries were less scrutinized, however, and in the military, machismo often prevents soldiers from seeking help. So while doctors have only once diagnosed him as suffering a concussion during his military service or his countless hours on athletics fields, Daniels now suspects he’s experienced at least a half dozen throughout his life.

He underwent psychotherapy at the local Veterans Affairs hospital, but the nightmares and sleeplessness continued, unabated. Then, this past June, just as he was about to resign himself to living with the war’s lingering aftereffects—and 10 long years since he’d returned home—Daniels experimented with hyperbaric oxygen therapy, also known as HBOT.

Everything changed.

If anything, Daniels says he now sleeps too much: eight hours of uninterrupted rest during the week, and 10 on weekends.

“My body is just now catching up on the rest it’s needed for a decade,” he explains.

HBOT is just one of the many treatments presently being considered by researchers as a viable option for concussed patients, with hundreds of millions of dollars being spent to determine better ways to accelerate recovery treatments in both acute and chronic patients.

To date, they’ve yielded mixed findings.

THE QUEST FOR A CURE

U.S. taxpayers have so far paid $70 million for a trio of HBOT studies, according to The New York Times. All three studies attributed improvements to a placebo effect—essentially, the patient’s belief in the treatment. Despite these results, Congress this year approved funding for yet another HBOT study.

Another potentially game-changing analysis is being conducted by researchers at the University of Buffalo and could upend the decades-old notion that rest is the preferred form of concussion treatment: Researchers are currently analyzing whether light aerobics could speed recovery time among recently concussed young athletes.

Then there’s the National Football League (NFL), which has drawn criticism for failing to address its concussion crisis sooner, announcing before the current season that it would invest $100 million to “support independent medical research” on concussions. The league’s outsized spending coincides with a new policy calling for players who appear too dazed on the field to undergo a so-called “concussion protocol” before they’re cleared to return to gameplay.

The NFL’s outreach and evolution of internal on-field policies comes on the heels of a $1 billion class-action settlement between the league and thousands of retired players who’ve suffered long-lasting brain injuries from head trauma throughout their careers. Last spring, NFL Executive Vice President Jeff Miller acknowledged for the first time what many in the medical field had long suspected: a connection between repeated blows to the head and the degenerative brain disease chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE), which can only be diagnosed posthumously.

Experts credit the NFL’s unprecedented admission and new technology enabling physicians to better understand brain injuries with raising the public’s awareness about concussions to record highs.

“Concussion has been around for a long time, and we’ve been talking about it for a long time. I think technology is now catching up, and as a result of that, there is an opportunity in acknowledging the fact that concussion just isn’t a singular event that goes away in three weeks or three months, and we can now start to measure the effects of those injuries and the technologies” being used as treatments, says Dr. Alan Sherr, owner and operator of Northport Wellness Center and founder of Hyperbaric Medical Solutions in Woodbury, which treats patients with concussions.

The pervasive use of improvised explosive devices (IEDs), such as those experienced by Daniels and other servicemen and women returning home to the United States from the conflicts in Iraq and Afghanistan, has also increased public awareness about TBIs—as well as a growing body of research suggesting their direct links to PTSD.

In 2012, scientists at the University of California at Los Angeles training rats that had experienced concussive brain trauma with fear-conditioning techniques made a startling discovery:

“We found that the rats with the earlier TBI acquired more fear than control rats (those without TBI),” Dr. Michael Fanselow, senior author of the study, explained at the time. “Something about the brain injury rendered them more susceptible to acquiring an appropriately strong fear. It was if the injury primed the brain for learning to be afraid.”

Analysis of brain tissue of the subjects’ amygdala—an area of the brain that responds to fear—revealed more receptors for neurotransmitters that promote learning, suggesting “that brain injury leaves the amygdala in a more excitable state that readies it for acquiring potent fear,” said Fanselow.

The findings suggested people who suffered even a mild TBI were more likely to develop an anxiety disorder, and underscored the importance of properly managing stress following such an injury.

Another study the following year including more than 1,600 service members who were assessed prior to their deployment to Iraq or Afghanistan, as well as three months after returning, found that troops who experienced a TBI were twice as likely to develop PTSD.

Dewleen Baker, a psychiatrist at UCSD and the VA San Diego Healthcare System, and one of that study’s authors, then partnered with Mingxiong Huang, a biomedical physicist at the University of California, San Diego, who had been using magnetoencephalography, or MEG, to measure neurological electrical activity in concussed subjects.

According to a joint paper published earlier this year in Psychoneuroendocrinology, scanning the brains of servicemen and women and civilians who experienced TBIs reveals abnormally low-frequency magnetic activity, with hyper-activity in the amygdala, and hypo-activity in pre-frontal cortex in individuals with PTSD.

Perhaps as a result the recent NFL revelations linking TBIs to the gridiron, more and more children are becoming aware, too.

Dr. Jennifer Gray, co-medical director of St. Charles Hospital’s ThinkSmart! Concussion Management Center in Port Jefferson, describes concussion awareness as “unavoidable” because of the deluge of coverage in the media.

“Over the course of the years that I’ve been doing this, I think most of the kids are really honest about their symptoms nowadays because they see the tragedy of what happens if they’re not,” she tells the Press.

As the search for the perfect concussion treatment continues, one thing is certain: It’s never too early for athletes to learn about the warning signs of traumatic brain injuries.

TREATING STUDENT ATHLETES

St. Charles’ concussion management center sees about 3,000 patients with potential concussion symptoms each year, the hospital says.

For many young athletes in contact sports, suffering a concussion—and other sports injuries—is an inevitable result of banging helmets, heading balls in soccer, or performing aerial feats in cheerleading. Short of stopping kids from engaging in athletics altogether, the more preferable option is to make sure concussed athletes are diagnosed early.

To that end, St. Charles’ concussion center has established a program with more than 42 school districts on Long Island, giving the hospital access to students’ neurocognitive baseline testing, which they can then compare to a concussion examination. Since the program was established in 2010, the center has amassed more than 30,000 baseline tests, which examine immediate memory, delayed memory, reaction time and processing speed.

“They compare it to themselves, which is the beauty of a baseline test,” says Gray. “So they take the test before they’re injured, and then after injury, the doctors can re-test them and see if there’s a significant change in their ability to do any of those tasks.

“If they don’t have a baseline on file, they can be compared to normative data,” she continues. “But we definitely prefer that we compare them to themselves.”

Baseline testing is not a fail-safe measure, however, since it focuses only on neurocognitive functions. Laura Beck, director of St. Charles’ concussion management center, calls it “one piece of a complicated puzzle,” because symptoms vary among concussed patients.

For some student athletes, the baseline test is “not even a factor in determining whether they’re ready to go back to play if kids are having real issues in the neurocognitive area,” explains Gray, adding, “It might be more useful than other kids having more physical symptoms.”

Recovery times also vary.

The athletes who visit St. Charles must complete a “return to play” protocol before they are cleared to rejoin their teammates. That means they must be symptom-free, return to baseline on their neurocognitive tests, and pass a physical exam. But that’s not all: Patients must also go through a “gradual return to play” over the course of a series of five days, where they progressively increase levels of exertion so physicians are confident symptoms won’t return.

CHALLENGING CONVENTIONAL WISDOM

How the body responds to physical exertion soon after suffering a concussion is the subject of a promising study being conducted by researchers at the University of Buffalo.

Its goal, as the university outlined in a press release last year, is to “evaluate for the first time a treatment protocol for concussion.”

“We know that exercise is good for the brain, in general, because it increases a protein called BDNF (Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor), and they’re studying whether increasing that level after concussion would help the brain recovery,” Dr. John Leddy, director of the Concussion Management Clinic in the Jacobs School of Medicine and Biomedical Sciences at UB and a North Babylon High School graduate, tells the Press. “There’s evidence of that in animals, but not humans.”

For humans, the question, Leddy says, is: “How soon can you introduce” exercise to a concussed brain. And if the body does not show any adverse effects, the next obvious question is: Will it help patients recover faster?

The answer, Leddy acknowledges, has been unattainable—until now.

In its mission to resolve that mystery, the school will hook up 100 13 to 17-year-olds to a heartrate monitor and record their reaction to light aerobics on a stationary bike or treadmill.

When the university announced this test, it highlighted the results of Julia Whipple, a 16-year-old high schooler from western New York who was injured playing soccer, completed the study, and recovered—she’d also expressed excitement about exercise as a form of treatment instead of languishing at home “wait[ing] for my symptoms to disappear.”

For years, conventional wisdom stressed that patients refrain from activity that could worsen their condition, such as avoiding bright lights, reading, exercise, and even leaving the house.

“I think that’s changing now,” says Leddy.

Leddy recommends rest immediately following a concussion—but, “after the first two or three days, when the symptoms are calming down, now you can start to get more active again,” he adds. “Again, you shouldn’t be playing a sport yet, but you can start to get more active, and we think we might even be able to get athletes exercising soon after concussion, to help them recover.”

While it seems rest would be far from harmful, research has shown it to cause depression in some concussed patients, which could be attributed to their removal from social interaction. Upending a teenager’s social life is not ideal, Leddy says.

“For the 80 percent of people who are going to recover in a week or two, that kind of worked pretty well,” Leddy says. “But for the 20 percent who don’t, it doesn’t work well at all. It doesn’t speed their recovery. Just resting and doing nothing, first of all, doesn’t help, and also then makes things worse, because now you’re taking a teenager out of his or her social life.”

Dr. David Cifu, Virginia Commonwealth University professor and concussion researcher and a Syosset High School graduate, echoes that sentiment.

“What we can do is optimize the body otherwise,” Cifu tells the Press. “Let’s talk to these kids and young adults about diet and exercise and sleep and anxiety management, and when can you safely return to play. You know, the notion that you’re supposed to be kept in a dark room or kept home from school is stupid.”

“The body—it doesn’t do well with rest,” he adds. “Rest is the antithesis of what a young person should be doing.”

As is the case with most injuries or diseases, early diagnosis is key to preventing the condition from getting worse, continues Leddy.

“If you think a child hasn’t gotten a concussion, then remove the child from the game or contest or practice, because [what] we know from animal and human studies is, the worst thing you can do is hit a concussed brain again before it’s recovered,” he explains. “Then you can revert what might just be a minor injury into a major injury, and then you magnify the symptoms and you delay recovery substantially.”

For those already struggling with the long-term ramifications of concussions, the quest for the most effective treatment continues.

HYPERBARIC OXYGEN THERAPY

Daniels, the U.S. Army vet, had been visiting Dr. Alan Sherr’s wellness center in Northport for about 20 years, for treatment on his back. Eventually, his wife, a physician assistant, landed a part-time job at Alan Sherr’s hyperbaric treatment office in Woodbury after growing exhausted with her commute to the Bronx. Once there, she advised her husband to give the treatment a shot, since nothing else had helped ease the effects of his PTSD.

Beginning in June, Daniels began a five day-a-week regimen, in which he reclined inside a hyperbaric oxygen tank for 60-minute sessions. His sleep improved almost immediately, he says, adding that the nightmares dissipated about halfway through the therapy.

Cases like Daniels’ have those in the hyperbaric field excited about HBOT’s potential as a viable treatment for concussions and other TBIs. To understand why those who offer hyperbaric oxygen therapy are so convinced it could help patients with brain injuries, even though the Federal Drug Administration (FDA) does not approve it as a viable treatment for TBI, consider how the therapy is utilized for other maladies.

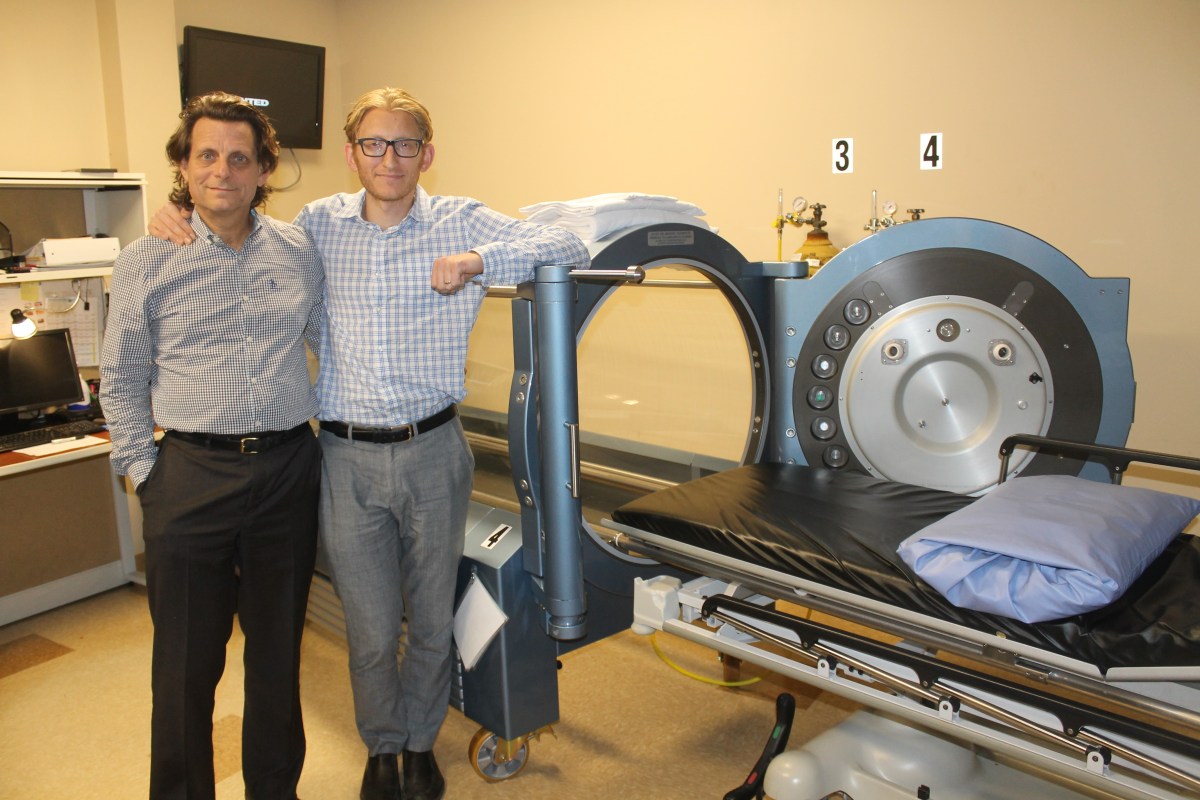

A hyperbaric chamber increases oxygen to the area that is at risk, and by doing so, could reduce degeneration and help heal wounds, explains Alan Sherr’s son, Dr. Scott Sherr, a medical advisor for Hyperbaric Medical Solutions who is certified in hyperbaric oxygen medicine. If you flood that area with oxygen “you can potentially prevent some of the tissue from dying,” he says.

The therapy has been approved by the FDA as a viable, effective treatment option for 14 conditions, including, among others: traumatic ischemia, severe anemia, thermal burn injury, carbon monoxide poisoning, decompression sickness, and osteomyelitis, aka chronic bone infections.

“We know it works,” continues Scott Sherr, citing other FDA-approved hyperbaric treatments. “What hyperbaric therapy is doing is healing the wounds in the brain that are not being healed by the body’s natural processes. And it’s super-charging and accelerating the healing process otherwise.”

HBOT can help reduce swelling, and even regenerate blood vessels, to help increase bloodflow and ensure that much-needed oxygen reaches damaged areas it otherwise would not, says Scott Sherr.

“What you really need is the scaffolding, or the regeneration of blood vessels, to create the environment where you can get long-term flow to those tissues,” he adds. “In somebody that had a chronic injury or a longer term injury, you need to create the scaffolding, or create the infrastructure for those cells to continue to be regenerated over time.”

When the U.S. departments of Defense and Veterans Affairs analyzed the results of its latest study of soldiers who had been recently concussed or were suffering from post-concussion, however, they found no significant difference between a group receiving 100-percent oxygen and a so-called “Sham” group receiving normal air at less pressure.

“It’s probably a placebo effect just from participating,” Col. Scott Miller, an infectious disease specialist at the U.S. Army Medical Materiel Development Activity at Fort Detrick, Md., concluded when the results were released. “These participants met with research teams and hyperbaric technicians for several hours per day. It was a fairly intense interaction.”

Cifu, who has worked with the VA and is well acquainted with the government’s HBOT studies, is not entirely sold, either, even after recognizing that some patients did express feeling better.

“I know people are making a big deal about it,” Cifu tells the Press. “And that’s why we’re studying it yet again, because there’s a little data that maybe stressed related things that we see in PTSD that you can also see in brain injury that got a little bit better, but it wasn’t huge—which is what people are missing.”

Scott Sherr argues researchers are missing an important finding from the studies: the physiological changes that happen under any increase in oxygen pressure. He points to the test patients that improved even after being exposed to less pressure and oxygen than the full treatment group.

“If you increase the amount of oxygen and circulation by 40, 50 percent, that’s a significant amount,” he says. “Even if we’re giving 90 percent in our treatment group. So there’s definitely something happening in the chamber.”

The studies have not all been unfavorable, however.

The Institute of Hyperbaric Medicine in Israel released its own assessment in 2013, finding that patients with prolonged symptoms saw significant improvement when undergoing the full HBOT treatment, as opposed to those who went two months with no treatment.

Its conclusion: HBOT can improve the quality of life in patients suffering from post-concussive syndrome.

Even though the focus of Hyperbaric Medical Solutions is on the hyperbaric therapy itself, its physicians also prescribe to a holistic approach to healing that encompasses several forms of therapy to supplement chamber treatment.

“The VA and the NFL and larger organizations have just missed the boat so far,” Scott Sherr says. “And you can argue as to why that is. There’s a lot of money riding on these patients. There’s a lot of injured veterans. There’s a lot of injured NFL players. But our hope is that we can create a center here, and in Northport, where we can actually show the world, and show, at least in our microcosm, that we’re having a significant effect.”

Daniels, who is now undergoing neurofeedback therapy at Northport Wellness—another treatment option that essentially maps, then reconfigures brainwaves through cognitive self-regulation—is an example of how an all-encompassing treatment regimen could prove to be an effective long-term solution.

The Sherrs understand hyperbaric oxygen therapy has its detractors, but they remain hopeful the treatment will receive its just due.

“You always start with the perspective of: Who are these people that are the skeptics? And from where do they come from in relationship to their orientation?” says Alan Sherr. “The greater the resistance, I know I’m on track. Because that means I’m butting up against someone’s belief systems.”

“We’re kind of in uncharted territory,” he adds. “We’re creating the systems, we’re looking to support it with appropriate analytics so that we understand their level of improvement and the possibilities, and that’s all new.”

They’re not alone.