By Tammy Scileppi

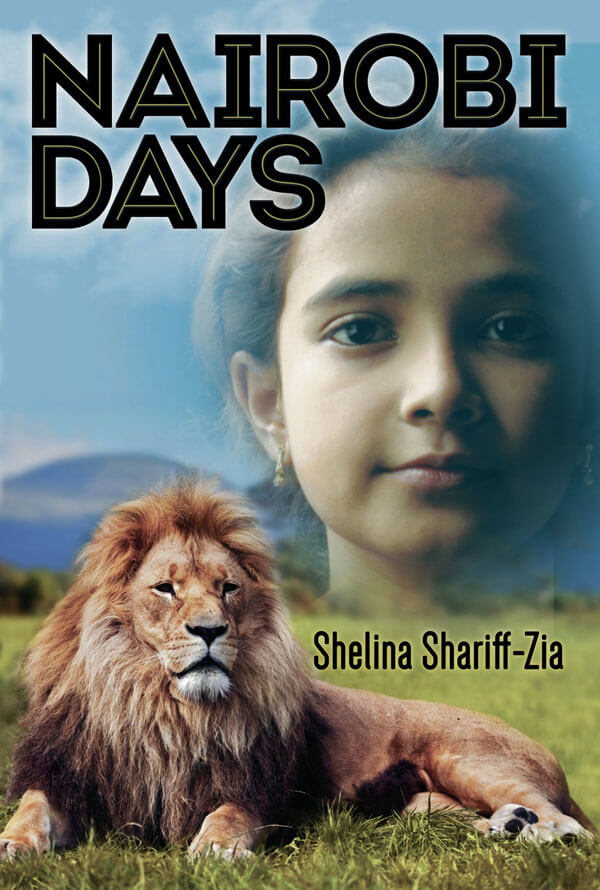

Shelina Shariff-Zia (pictured top) calls her new autobiographical novel “Nairobi Days,” a celebration of Indian and African culture. Indeed, she is part of both.

She writes: “On December 12th, 1963, Kenya became independent from the British. So we grew up together, Kenya and I. The day I was born, it started raining heavily in the early morning and never stopped for the rest of the day. People loved and worshipped the rain in Kenya as it meant the crops would grow well.”

The local author and journalist, who grew up in that turbulent African country, shares her fascinating real-life experiences as the young daughter of Indian immigrants living in the city of Nairobi — as seen through the eyes of her protagonist Shaza, a young woman with big dreams.

Baby Shaza is born on a Sunday morning, June 17, 1962. “As my family tells it, it stopped raining and a rainbow came out. As tradition dictates, Ma [the author’s real paternal grandma] held me and put honey on my tongue after the delivery so my first taste would be sweetness while she said the Shahada, the Muslim proclamation of the faith,” writes Shariff-Zia.

In “Nairobi Days,” she explores her unique mixed Indian and African heritage and invites readers on a journey that follows Shaza’s coming of age during the political upheavals of the 1960s, 1970s and 1980s.

The author, who described her novel as “a coming-of-age story, a love story, a political novel and above all a celebration of life,” will be speaking about her Nairobi adventures at the Central Queens Y in Forest Hills, at 67-09 108th St., on Monday at 1:30 pm.

The author’s close-knit Muslim family lived through difficult times in which the Indian minority was targeted. Eventually, she came to the United States and New York, bringing a complex cultural heritage with her.

Shariff-Zia and her husband reside in Forest Hills, which they call home.

The author writes that after Shaza is born, “Ma looked outside and said, this daughter will be lucky. She has brought her naseeb with her; she brought a rainbow. Since it was a Sunday, all the relatives came over to eat sweetmeats — baarfi and ladoos and see the new baby.…

“Kenya’s birth as an independent country the next year was even more dramatic.”

While the book is fiction, the author says it’s based on her life and experiences in Kenya. “I have tried to be as faithful to the history of Kenya as possible,” she said. “The street names, schools, hospitals, restaurants and buildings are all real places, some of which you can still visit today. Many of the characters are based on my own family but I have changed names and certain circumstances.”

As part of a proud family that emigrated from India, the author was the fifth generation to grow up in East Africa. She naturally embraced African culture and spoke Swahili.

“My classmates and friends were black African, and I thought of myself as Kenyan. At the same time, my family and community kept Indian traditions alive,” she explained. “We attended the mosque regularly and spoke Kutchi, an Indian dialect at home. We ate Indian food and what we called English food, which was Western dishes as well as some African staples like ugali, a maize-meal polenta-like dish. Both cultures were celebrated and enjoyed.”

Rewind back to the sixties 1960s, Shariff-Zia was growing up in Nairobi. Life was much different then.

“We lived in a sleepy suburb. There were goats and lots of chickens in the area as well as cats and dogs. A lot of bird life lived in the trees. Small snakes and chameleons were common. But we were only an hour’s drive from the Nairobi National Park, and like today, there have been times when lions wondered out of the park and into the suburbs,” the author recalled.

It isn’t easy for Shaza, a convent schoolgirl who is also a tomboy and always getting into trouble, to embrace the old ways and abide by strict societal and cultural mores. Her life is complicated.

Later in the book, during an edge-of-your-seat moment, she meets Idi Amin, the bloodthirsty Ugandan dictator, and makes a harrowing escape.

Even though she worked as a journalist for years, Shariff-Zia found writing fiction difficult. “It sounded fake,” she recalled. It seemed she was internalizing what her grandmother used to tell her: “Never talk about what happens at home, it’s like showing people your underwear.”

But everything changed after her mother was found to have bone marrow cancer in 2006. Her father had died four years before.

The doctors started drug treatment, but eventually, the family decided to bring its mother to Vancouver, where the rest of her family lives.

“I would ask her to tell me all about her life: as a child, a young woman and as a new bride and mother,” Shariff-Zia recalled. About a week after her mother died, in April 2012, she sat down at her computer and started typing her saga.

“I wrote more about my mother, my grandmother, my aunts, the people who worked for us, my cousins, everyone had their own story; even the dogs,” she said. “And then after about 150 pages, I started writing a love story. I wanted to recreate that feeling of being seventeen and really liking someone, having a head over heels crush on them.

Turns out no one in Kenya dates; people just sneak around, according to the author. Shaza falls for a Hindu boy. Sameer is smitten, but they come from two different religions. Shaza is torn between her sense of duty and longing for Sameer. Will the relationship survive her family’s disapproval and a long separation?

By the time her book was finished, Shariff-Zia’s story had evolved into so much more.

You can say that in many ways, the worldwide Indian diaspora is similar to the Jewish diaspora. So, in that vein, during the interview, the author also talked about her family’s experience emigrating from India to Kenya decades ago. Some of the Indians in the diaspora are Muslims, who fled pogroms and discrimination in their homeland.

The author left home when she was 19 to attend the University of Houston in Texas, in 1981, before transferring to Rice University in 1982.. After getting her master’s at Columbia, she returned to Kenya in 1986 and worked for the Aga Khan Education System, which ran 17 schools.

“I had a great job and enjoyed being back in Kenya. But at the same time, I missed my friends and life in New York,” she recalls. Though it was a hard decision, she moved back to NY in 1986 and got a job as a journalist, then married in 1991 and moved to Karachi, Pakistan, with her husband. Afterward, they lived in different cities and finally moved back to New York in 2005.

The author says she keeps in touch with an aunt and cousins back in Kenya, and also has a lot of friends there.

Surprisingly, she has never been to India.

Shariff-Zia teaches English at Bronx Community College and writes a blog. She is also working on her next book, a memoir about her family, and says she hopes readers enjoy her novel and realize how different life can be in other countries.

“I chose to write a love story between a Hindu boy and a Muslim girl as I think religion can sometimes create too many barriers between people,” she said. “I think people would be pleasantly surprised if they were more open to people from different ethnicities, races and religions.”

Globally, the 30-million strong Indian diaspora is considered one of the most influential and valuable communities. And having enriched their adopted countries, people of Indian origin living in different nations — like the author — have made a name for themselves in diverse fields: culture and culinary arts, music and cinema, academia and business, medicine and technology. And in literary circles, as well.

You can read more excerpts from the book at www.shelinashariffzia.com.