City Council candidate Amit Bagga was already facing an uphill battle. A first-time candidate running in one of the most crowded races in the city, Bagga and his team needed to collect hundreds of signatures from voters in order to get his name on the ballot.

However, the real complications began when Bagga and several members of his campaign staff learned they had been exposed to a person with COVID-19. Though signatures still needed to be collected, Bagga had to go into a 14-day quarantine during the final week of petitioning.

“It’s, of course, scary. When it happens, there is a degree of anxiety, and there’s a degree of concern that is very real,” Bagga said. “I think logic, common sense and just being prudent, clearly dictated that petitioning should have been canceled.”

Of the 26 City Council campaigns in Queens who responded to QNS’ inquiries, three reported that a member, or multiple members, of their volunteer team, staff or the candidates themselves had been exposed to, or contracted COVID-19 during the petitioning process. While not every campaign could confirm that contraction of the virus happened as a result of petitioning, in all cases, petitioning, which ended the last week of March, was interrupted and the process to get on the ballot became even more of a challenge.

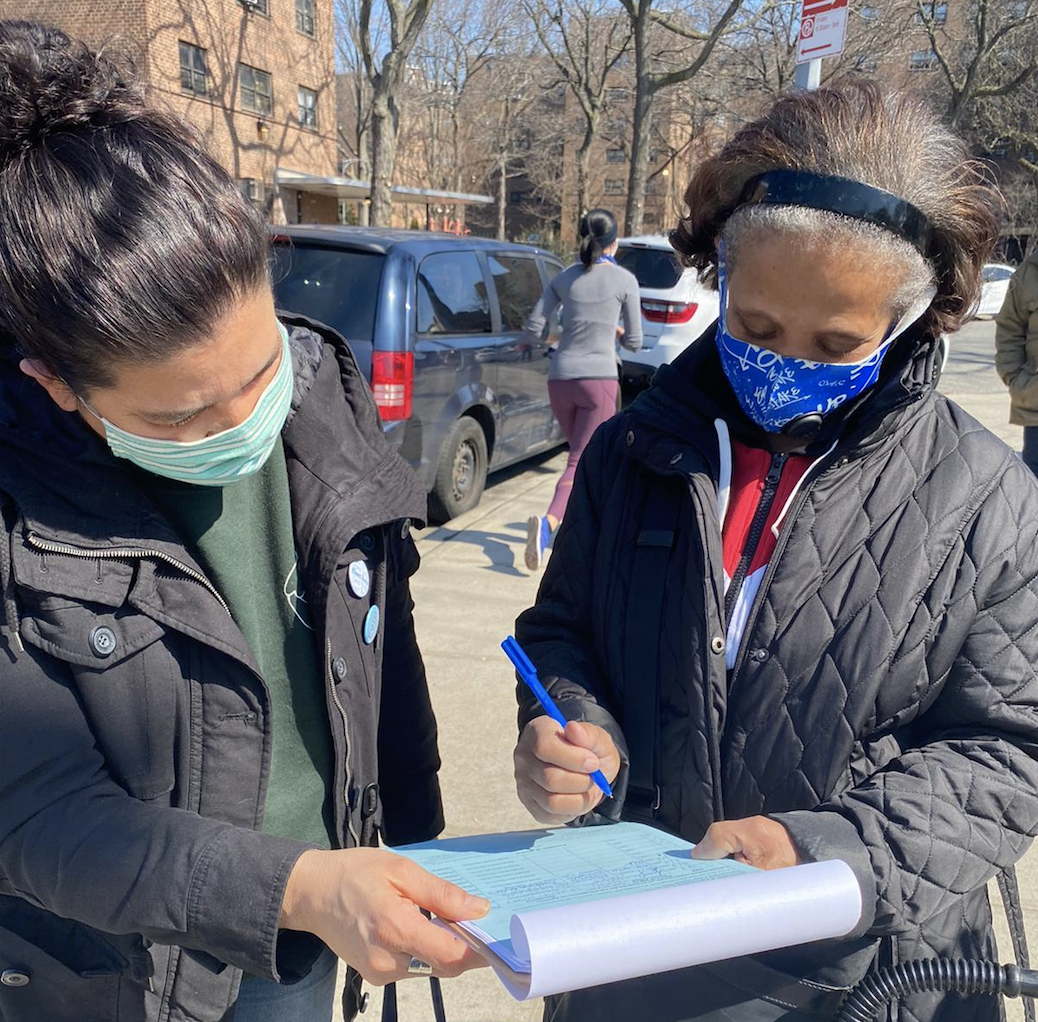

Petitioning requires candidates to collect in-person signatures from voters who live in the candidate’s district and are registered in the candidate’s party.

Despite calls from over 100 candidates and lawmakers citywide to call off the signature collection because of the threat COVID-19 posed to both petitioners and voters, the process wasn’t canceled. Instead, the number of required signatures required for City Council candidates was reduced from 900 to 270.

For a handful of campaigns, collecting fewer signatures didn’t keep them safe from the virus, which has infected around 18,000 New York City residents in the past week and killed nearly 50,000 New York state residents since it first began spreading a year ago. Even for those campaigns that were not exposed to COVID-19 during petitioning, many said the risk of contracting the virus weighed heavily during the process.

An overwhelming number of campaigns noted that they were “fortunate” to avoid being exposed to or contracting COVID-19.

In last year’s elections — the first during the pandemic — Governor Andrew Cuomo reduced the number of needed petition signatures by 70 percent. The same reduction applied to this year’s process.

But as was the case last year, candidates running for office in 2021 called on petitioning to be canceled entirely.

Over 100 lawmakers and candidates, including many from Queens, sued the governor and Mayor Bill de Blasio in February in an attempt to cancel petitioning outright, citing the risk the activity posed to candidates, voters and volunteers.

“I feel really hesitant about sending people out there who will volunteer for me, or be on my campaign, and asking them to risk exposure to COVID to get me on the ballot,” Queens borough president candidate and lawsuit plaintiff Jimmy Van Bramer told QNS at the time. “It’s a choice no one should have to make.”

The lawsuit was struck down in court, and petitioning went on.

About a month later, Van Bramer was one of several candidates across New York City to contract COVID-19 during petitioning.

“Given my extreme caution as a caregiver for my mother, I believe I contracted COVID from petitioning, which the governor refused to cancel despite the public health emergency and a lawsuit from candidates,” Van Bramer said. “We suspended our volunteer petitioning operation after I tested positive, and prior to that, our campaign had taken precautions, such as making rubber gloves and hand sanitizer available, used different pens and standing six feet apart.”

Van Bramer ended up collecting more than 4,300 signatures, almost four times the required 1,200 for borough president candidates. Like many candidates, he called on opponents not to challenge each other’s signatures, a process that might further put campaign workers at risk.

Bagga, who is running for City Council for Van Bramer’s seat in District 26, was lucky enough not to contract the virus. However, when he and three members of his campaign staff were forced to quarantine, he had to figure out how he’d continue to collect signatures.

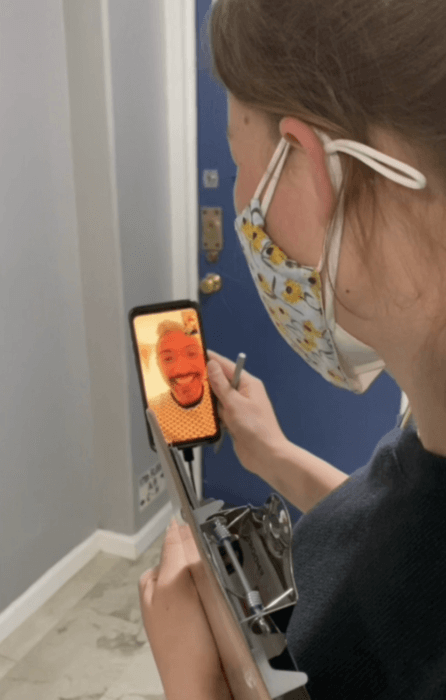

While locked away in his home, volunteers would go door to door to ask voters for signatures.

“And then they would say, ‘Amit would really like to speak to you directly,’” Bagga said. “If the voter agreed, the volunteers held up the phone in such a way that allowed the voter to see me and allowed me to see the voter and have a direct conversation.”

And it worked. Bagga collected the required 270 signatures, plus a 1,000-signature cushion, should any be deemed invalid. He even felt that his workaround still allowed him to make connections with voters, including one in particular who happened to disagree with his platform.

“He was just a joy to speak with,” Bagga said. “And, you know, it was both very different, and yet somehow incredibly fitting for the time that we’re in for us to be able to have a conversation like that.”

But the barriers stopping candidates and campaigns from connecting with voters have been plentiful, according to Evie Hantzopoulos, a candidate in City Council District 22.

Hantzopoulos is hosting more virtual events to facilitate connection, but she said many people are “Zoomed-out.” She added they still haven’t done any door knocking or canvassing – strategies used to connect with voters pre-COVID – as she thinks some people “might be uncomfortable” given the ongoing pandemic.

The vast majority of campaigns in Queens told QNS that staff, volunteers and candidates remained healthy during the in-person signature collection. Still, despite the precautions taken by nearly every campaign, none felt totally safe and many made alterations to the process to ensure fewer people could potentially be exposed.

Steven Raga, who is running for City Council in District 26, said many of their volunteers were fully vaccinated during the petitioning process, and for the time they weren’t, they wore masks, gloves, face shields and brandished hand sanitizers and multiple pens for single use.

Eugene Noh, campaign manager for Julie Won, who’s also running for City Council in District 26, said they took similar precautions. They had about 20 volunteers and were able to collect more than 2,000 signatures within two weeks of the process.

“On [March 17], we decided to stop gathering signatures to eliminate the risk of catching or spreading COVID-19,” Noh said.

Mike Dillon, campaign manager for Badrun Khan, who’s also running for City Council in District 26, said they focused on petitioning in fixed locations and used tables to reinforce social distancing, which also allowed them to stock safety supplies they bought in bulk.

Nicholas Velkov, a City Council candidate in District 22, said his first safety measure was to collect signatures on his own.

“I didn’t ask any volunteers to go out for me. Roughly 80 percent of my signatures were collected by me,” Velkov said.

The same was true for Catherina Gioino, also running in District 22, and Kenichi Wilson, who’s running in District 32.

“My friends actually volunteered and I turned them down,” Gioino said. “So I got 500-ish signatures myself with a vaccinated friend.”

Tiffany Cabán, who is running for City Council in District 22, stated that her campaign “agonized” over the amount of signatures they’d need to collect in order to make it onto the ballot successfully while keeping people safe.

Cabán, who announced they met their goal a week after petitioning began, said the governor’s decision to allow petitioning was “yet another example of his failed leadership.”

“He put us in an impossible position where participating in democracy meant putting your health on the line,” Cabán said.

But despite taking precautions, as many have learned this past year, the risk of COVID-19 couldn’t be eliminated entirely.

“I was very confident in my own practices, in terms of following strict protocols around COVID. It just so happens that the person who did contract COVID, that I was around, also was very strict about following protocols,” Bagga said. “And that, actually, in some ways gave me a little pause, because I thought, ‘Well, if you know this person is so meticulous and I’ve been meticulous, and they could still contract it, what does that mean for me?’”

Hantzopoulos said neither she nor her staff or volunteers contracted COVID-19 while petitioning. They were able to meet their goal in less than a week, utilizing an appointment system, where voters could set up a time to sign the candidate’s petition.

Ultimately, for Hantzopoulos — who’s led various COVID relief efforts since the height of the pandemic — petitioning was an unnecessary risk.

“I have been on the ground doing COVID relief for the past year, that’s where we should be focusing our efforts,” Hantzopoulos said. “If you’re going to put yourself at risk, it should be for something like that. There’s other ways to get people on the ballot.”

Additional reporting by Clarissa Sosin and Bill Parry.