By Philip Newman

More than six decades after D-Day, France has proclaimed its gratitude to its American liberators by bestowing the Legion of Honor on nearly a score of former GIs, including two Queens residents.

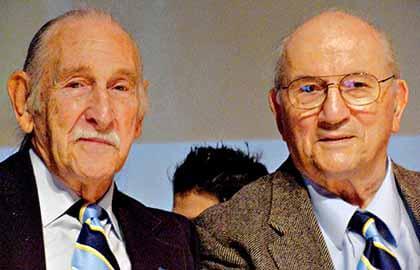

“I want to say, quite simply, that we will never forget what you did and that we will try to be worthy of your example,” said French Consul-General Philippe Lalliot, before pinning France’s highest decoration on 19 military veterans, including Sam Resnick of Bayside and Vincent Minecci of Queens Village.

“You did not go off to fight on a foreign continent thousands of miles away because the enemy was directly threatening your homes and families,” Lalliot said at a ceremony both solemn and moving Nov. 11 at the Lycee Francais — French high school — on Manhattan’s Upper East Side.

“You went off to fight for a cause and for values that transcend the individual democracy, the rule of law, freedom,” Lalliot said. “France would not be as she is today — free and sovereign — without all the veterans, notably French and American, who fought for her.”

The school choir opened the ceremony with the national anthems of both countries: “La Marseillaise” and “The Star-Spangled Banner.”

As Lalliot pinned a medal on each recipient, a ninth-grade student — pupils are now studying this period of French history — assigned to that particular veteran read a short summary of the veteran’s combat record in France.

They are as follows:

• Pfc. Resnick, cannoneer of Co. “D” of the 399th Infantry Regiment of the 100th Infantry Division: Resnick landed in Marseille in October 1944 and took part in the Northern France and Ardennes campaigns. His unit liberated the towns of Raon l’Etape, Moyenmutier and Bitche. He was awarded the Bronx Star for meritorious service.

• Sgt. Minecci of “B” Co. of the 925th Field Artillery Battalion of the 100th Infantry Division: Landed at Marseille October 1944, took part in the Northern France and Alsace Lorraine campaigns. He participated in the liberation of Raon l’Etape. Minecci was wounded in action. He was awarded the U.S. Purple Heart and the Bronze Star for meritorious service.

Although they never met during the war, both Resnick and Minecci arrived in troop ships at Marseilles at a harbor blocked by half-submerged ships blown up by the retreating Nazi troops.

“We could not reach the mooring area and had to crawl across the hulks of these ships in making our way to the docks,” Resnick recalled.

Resnick, 84, a board member and past president of the 100th Infantry Division Association, said his unit then proceeded on a march toward the battlefront.

The 100th Infantry Division, in which Resnick and Minecci served, was part of the greatest flow of soldiers, munitions and war materiel in the history of warfare following the D-Day landings in Normandy June 6, 1944, in the campaign against the Germans, who overran France in 1940.

“When people ask whether I was wounded, I hesitate,” Resnick said. “I was assigned to military police in Berlin after Germany had surrendered. One day, one of our fellow MPs was cleaning his rifle and it accidentally fired with the bullet going through my big toe. But the war was over. No Purple Heart.”

Resnick’s colorful descriptions of life in a U.S. infantry outfit under frequent German bombardment and counter attack in a bitter winter and accompanying everyday horrors of warfare as the Germans are pushed relentlessly back make for fascinating reading.

The stories are on the 100th Infantry Division website under “Forgotten Memories.”

Resnick was instrumental in getting Bell Boulevard and 212th Street renamed “100th Infantry Division Blvd.” and Cross Island Parkway renamed “100th Infantry Division Memorial Parkway.”

Minecci, 89, told of an incident involving a nearly 100-pound radio that he and another soldier were carrying while under artillery attack by the Germans.

“I always say that radio saved my life,” Minecci said.

Minecci said an officer asked whether anyone knew about a certain kind of radio used in directing artillery fire.

“I had been sent to radio school in the states,” Minecci said. “So I raised my hand. Soon we were carrying this big radio in two parts.”

Minecci said, “The Germans opened up with their big guns, blowing up a place where I would have been if I had not left with the radio.”

He was also wounded in the hip by a German sniper and taken to a field hospital.

“I remember the date: It was Nov. 13, 1944,” he said.

“While I was in the hospital, a general came in and talked to me and other wounded soldiers,” Minecci said. “It was Brig. Gen. Anthony McAuliff.”

McAuliff became famous around Christmas 1944 in the Battle of the Bulge, when the Germans ordered his beleaguered troops to surrender at Bastogne, Belgium, and he defied the Nazis with a reply of, “Nuts!”

Prior to 2004, the only Americans eligible for the Legion of Honor were those who fought in France in World War I.

The French government said it expects to award about 100 Legions of Merit in the United States annually through its 10 consulates in America.

The Legion of Honor is predominantly but not exclusively awarded to members of the military. It was established in 1820 by Napoleon Bonaparte.

Reach contributing writer Philip Newman by e-mail at timesledgernews@cnglocal.com or phone at 718-260-4536.