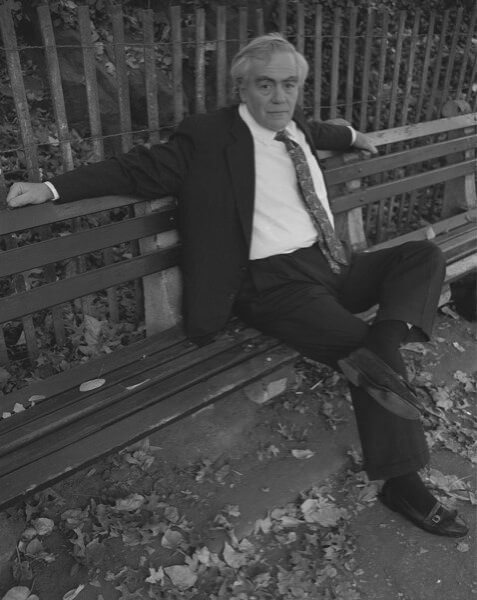

By Michael Shain

Unlike the vast majority of household names who were born and raised in Queens, Jimmy Breslin — who died last Sunday at the age of 88 — never ever had to tell anyone where he was from.

The most-famous New York columnist of his generation died in the West Side Manhattan apartment he shared with his wife, the former City Councilwoman Ronnie Eldridge, 16 or so miles from Richmond Hill where he grew up.

No matter, his attachment to Queens was an indispensable part of who Breslin was — in no small part because he played a starring role in shaping the life of the borough as it is today.

In 1985 Breslin broke the story of how Donald Manes, the borough president of Queens at the time, had been caught taking bribes from vendors doing business with the city. In a series of columns on the scandal, Breslin made the sidewalks of Queens Boulevard in front of Borough Hall and the State Supreme Court building look like Sodom and Gomorrah and Kew Gardens the home of all that was unholy about the New York of the 1980s.

Municipal government was never the same.

Breslin was born on Oct. 17, 1928 and grew up at 101st Avenue and 138th Street, just south of where Jamaica Hospital is today. His father and namesake abandoned the family when he was 6. He was raised with his younger sister by several family members.

Breslin barely graduated from high school and attended college in name only. In a day when newspaper people rarely were schooled past the 12th grade, he got his first job in Jamaica as a copyboy at the Long Island Press, within walking distance from his house. He never learned to drive, a fact he was especially proud of.

If he helped tear Queens apart at one point in his career, he also was a walking billboard for what Queens people were capable of. He created characters like Fat Thomas, a bookie, and Klein the lawyer, who spoke and thought in a language that was pure Queens. He made the borough seem almost romantic. He also published a column every New Year’s Day of the people he was not speaking to in the year ahead.

He wrote what is considered one of the best novels of modern times on living in Queens, “Table Money,” about the wife of an abusive Irish construction worker — a sandhog — engaged in the decades-long project of digging a second water tunnel in New York.

When he died, Breslin had not been working as a columnist for more than a decade. A generation of newspaper people knew him only as a ghost of deadlines past. But it is difficult to underestimate his stature as a civic figure in New York in the era between John F. Kennedy and Rudy Giuliani. Like Michael Jordan or Tiger Woods, he dominated his business utterly. Before Breslin, there were no columnists quite like him. After Breslin, everyone wanted to be him.

He learned early on that the way to do a big story — the Kennedy assassination, the AIDS epidemic — was to tell it as a little one. He found the man who dug JFK’s grave at Arlington Cemetery. He haunted the bars and cafes of Ridgewood and Woodside in search of gangsters and wronged wives.

Years ago when columnists’ importance was measured by their access to the White House, Breslin knew people like the desk sergeant at his local precinct in Forest Hills — because back then that was the central booking facility in Queens.

At one time or another, Breslin wrote a column for every newspaper in the city — the Daily News, The Post, Newsday, the Herald -Tribune — except the one he professed to hate, The New York Times. In a column, he questioned the basic fairness of a guy from Queens who wrote books always getting reviewed by Manhattan guys “who parted their names in the middle,” a dig at The Times’ book critic of the era, Christopher Lehmann-Haupt. The Times critic apparently did not recognize Breslin’s genius quite as clearly as Breslin did.

And in Breslin’s eyes, there was no greater sin.