Few Queens residents may realize just how important two landmarks in Flushing were in the effort to secure freedom for slaves during the 19th century.

Our thanks go out this week to Grace Friary, Rob MacKay (a former Ridgewood Times reporter) and Rosemary Vietor, who prepared for us the following report on the Bowne House and the Quaker Meeting House, and their roles in the Abolitionist Movement:

Last month, the NYC Landmarks Preservation Commission unveiled “New York City and the Path to Freedom,” an interactive website that educates users of all ages about local landmarks that featured prominently in the Abolitionist Movement and the Underground Railroad.

Two Flushing landmarks – the Bowne House and the Quaker Meeting House – are described along with 16 other properties in other boroughs.

The timing is perfect because recent research in the Bowne House archives (i.e. diaries, passports, deeds, correspondence) has uncovered new information about how residents – mainly the Bownes and the Parsons – were ardent, active abolitionists. (Many were Quakers, too.)

First an admission: Bondage was legal in NYC until 1827, and Queens had one of the largest pockets of slaves in the entire northeast. At the same time, the borough was also a hotbed of abolitionism through the Civil War and into Reconstruction, with Flushing as the center of these activities.

An early Bowne House resident, Robert Bowne (1744-1818), helped found the Manumission Society of New York, which lobbied for laws that ended slavery in the state, provided legal assistance to blacks, and established the African Free School in 1787 to educate black children in Manhattan in 1787.

Manumission refers to when an owner frees slaves voluntarily or in exchange for money or goods. This differs from emancipation or abolition, which involves freedom due to government action.

Another Bowne House resident, Samuel Parsons (1771-1841), owned a large arboretum and nursery in Flushing. According to family lore, the Quaker minister would travel to southern states to buy and sell trees and plants – and return with escaped slaves hiding in his wagon along with the rhododendrons and azaleas.

These runaways might have gone from the Parsons Nursery to a mill on the Flushing River, where they would head north under cover of darkness.

Samuel Parsons was married to Mary Bowne (1784-1839). One of their sons, Robert Bowne Parsons (1821-1898), was a “conductor” on the Underground Railroad, the secret network of routes and safe houses used by escaped slaves to travel to freedom.

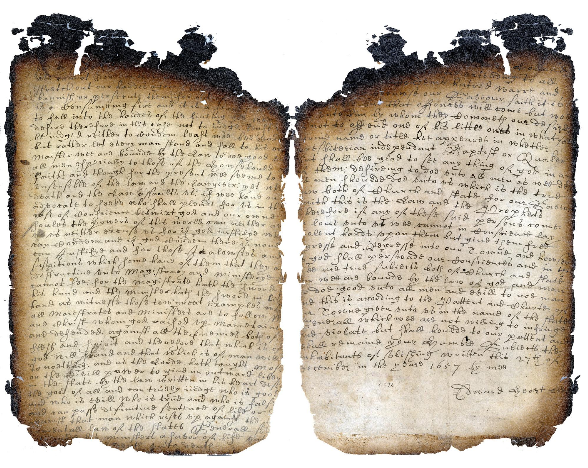

A recently discovered letter in the Bowne House archives in the papers of a Brooklyn pastor notifies him of an imminent arrival of slaves.

In his obituary, Robert’s brother, Samuel Bowne Parsons (1819-1906), boasted “that he assisted more slaves to freedom than any other man in Queens County.”

For many years, the Bowne House, a 17th-century, wooden-frame English Colonial saltbox at 37-01 Bowne St. that is now open to the public, was a stop on the Underground Railroad. Residents frequently warded off bounty hunters who sought to kidnap blacks (slave and free) to sell in southern states.

The Quaker Meeting House also played an important role in the history of abolition. It was also near and dear to the Bowne and Parsons families.

In addition to being the Bowne House’s namesake, English immigrant John Bowne (1627-1695) was one of New York City’s earliest and most committed Quaker leaders. He helped buy the property at 137-16 Northern Blvd., where the 1694 meeting house currently stands.

Many prominent Quaker leaders of the anti-slavery movement (i.e. William Burling, John Farmer, Matthew Franklin, Elias Hicks) planned their political activism at the meeting house. Quakers did not use headstones until the mid-1820s, so it’s difficult to determine all of the abolitionist leaders who are buried in the graveyard. Nevertheless, it’s believed to be the final resting place for Burling, Franklin and John Murray Jr., who co-founded the Free School Society and The New York Manumission Society.

It’s not confirmed, but the grapevine claims that the immigrant John Bowne is there, too, in an unmarked grave.

Old Timer’s Note: One could argue that the Bowne House and Quaker Friends House are not only two of the most important historic sites in Queens, but also perhaps two of the most important sites in the fight for freedom in America.

Decades earlier, while under Dutch colonial control, the Quakers of Flushing (then known as Vlissing) created in 1657 what came to be known as the Flushing Remonstrance. It came to be considered a forerunner of the First Amendment of the U.S. Constitution, enacted in 1789, which ensured the freedom of religious worship.

The Flushing Remonstrance was a petition to the Director-General of New Netherlands, Peter Stuyvesant, who had instituted an ordinance prohibiting the practice of any religion except for the Dutch Reformed Church. This led to acts of persecution, and 30 Quakers in Flushing signed on to the petition urging Stuyvesant to recognize people of other faiths.

In the Remonstrance, the Quakers condemned persecution against any person, noting: “We are commanded by the Law to do good to all men . . . That which is of God will stand, and that which is of man will come to nothing . . . Our only desire is not to offend one of these little ones, in whatsoever form, name or title he appears . . . There if any of these said persons come in love unto us, we cannot in conscience lay violent hands upon them, but give them free egresse or regresse into our town and houses . . . This is according to the Patent and Charter of our town . . . which we are not willing to infringe or violate.”

The Remonstrance did little to sway Stuyvesant. After receiving the Remonstrance, he ordered the town of Vlissing’s government changed. Persecution continued, and arrests were made.

The targets of persecution included John Bowne himself, who allowed Quakers to meet in his home. In 1662, Bowne was arrested and subsequently ordered by Stuyvesant expelled from the colony. After being sent to The Netherlands, Bowne made appeals to the Dutch West India Company, which ordered Stuyvesant to end religious persecution.

Bowne returned to Flushing in 1664 — the same year that the British took control of New Netherlands and renamed it New York.

The Bowne House hosts tours on Wednesdays from 1 to 4 p.m. Admission is $10 per person, and there are special rates for group and school tours. Bowne House members are admitted free. For more information, visit bownehouse.org, call 718-359-0258 or email office@bownehouse.org. (Those interested in organizing school tours can email bownehouseeducation@gmail.com.)

* * *

If you have any remembrances or old photographs of “Our Neighborhood: The Way It Was” that you would like to share with our readers, please write to the Old Timer, c/o Ridgewood Times, 38-15 Bell Blvd., Bayside, NY 11361, or send an email to editorial@ridgewoodtimes.com. Any print photographs mailed to us will be carefully returned to you upon request.