By Rich Bockmann

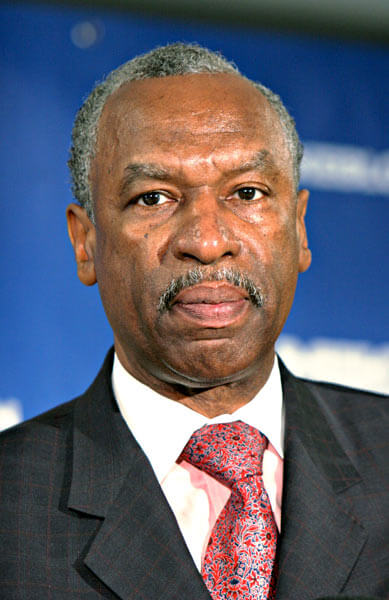

An arm of the Rev. Floyd Flake’s Allen AME Church turned over a pair of derelict apartment buildings to a Brooklyn-based nonprofit developer several months ago after it failed to renovate them under a city-run affordable housing program, TimesLedger Newspapers has learned.

In June, Flake’s Allen Affordable Housing Development Fund Corp. sold two southeast Queens buildings that had appeared on the city public advocate’s slumlords list to the Mutual Housing Association of New York, a Brooklyn-based developer that took over the gut-rehabilitation agreement Allen Affordable made with the city Department of Housing Preservation and Development in 2006, property records show.

A spokesman for the department said Allen Affordable’s project stalled due to capacity issues and challenges with tenants, and the two partners agreed that in the interest of moving the project forward a new developer should be brought in.

Records show the construction delays caused HPD to pull the federal funding allocated to Flake’s group, and the Brooklyn-based non-profit is currently working on the renovations with most of the funding provided by a private partner.

Since at least 1997 the city housing agency had considered Flake, who at that point was leaving Congress, as a prospective developer to take over the two buildings — one at 107-05 Sutphin Blvd., and the other at 89-06 138th St. — under its Neighborhood Redevelopment Program, which allows the department to sell city-owned buildings to community-based nonprofits to rehab and operate as rent-stabilized, low-income housing.

In 2006, the City Council and the Mayor’s Office of Contract Services signed off on the department’s proposal to sell the two properties and an adjacent vacant lot to Allen Affordable for $3. The department loaned the developer $2,377,655 to perform a gut rehabilitation on the buildings — nearly two-thirds of which came from the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development’s HOME Investment Partnership Program, records show.

But when Allen Affordable failed to begin construction by a deadline set by HUD, the city pulled the federal funds rather than lose them.

“[T]his project has had a long history and a construction start continues to elude the city and designated developer for this project,” Adolfo Carrion, the Bronx politician and HUD’s regional administrator at the time, wrote in a December 2010 letter that was obtained by TimesLedger Newspapers.

“To avoid the loss of the fiscal year 2005 funds reserved for this project to another jurisdiction, the funds were cancelled by the city in HUD’s IDIS system so the city could reallocate those funds to other projects able to meet the HOME expenditure deadlines.”

Allen Affordable struggled to relocate some of the buildings’ tenants, in particular Frederick Jones, an Army veteran who lived in the Sutphin Boulevard building and worked as the superintendent when it was owned by the city.

Jones refused to temporarily relocate in order to clear the way for construction, claiming the allocation of federal funds entitled him and other tenants to further assistance beyond relocation.

“Where is the reimbursement for advisory services? For social workers? Reimbursement for hardships? You can’t just displace somebody with no supportive services,” he said.

Harold Flake, son of the minister and Allan Affordable’s vice president of real estate, said the nonprofit tried its best to accommodate Jones.

“We did everything we could to work with Mr. Jones and offered him several relocation options, but if someone doesn’t want to move, then they’re not going to move,” he said.

Jones took his case to court, filing several lawsuits claiming Allen Affordable and the government agencies had wilfully neglected him. In a motion dismissing one of the suits, Brooklyn Federal Judge Raymond Dearie wrote that Jones’ “repetitive and meritless” filings were only delaying his own goal of finding suitable housing and warned the court could prevent him from filing future complaints without a judge’s permission.

While the two sides battled it out, living conditions at both buildings deteriorated so much so that in 2010 their landlords showed up on then-Public Advocate Bill de Blasio’s list of worst landlords.

Flake said that was the final straw: that any bad publicity related to his father — a high-profile, powerful political figure — essentially scared off any partners who could help get the project back on its feet.

Jones remained in his apartment until early 2012, when the city Department of Buildings issued a vacate order, citing structural instability that caused the building to shake.

The city worked to transfer its agreement with Allen Affordable to MHANY, the Brooklyn developer, in June and to put the proper funding in place. MHANY received the majority of its funding — more than $4 million — from the Community Preservation Corp., a non-profit lender with a major presence in the city and state.

Reach reporter Rich Bockmann by e-mail at rbockmann@cnglocal.com or by phone at 718-260-4574.