Throughout the COVID-19 pandemic, Queens residents have shown their resilience, perseverance and strength in the battle against the coronavirus that has taken countless lives, and impacted the borough’s economic, social and political landscape.

As COVID-19 swept across the globe, it had finally made its way to New York City in early spring. In Queens, the first confirmed case of the virus was reported in Far Rockaway on March 7.

Senator James Sanders Jr. announced that a 33-year-old male Uber driver had contracted pneumonia and was taken to Far Rockaway’s St. John’s Espiscopal Hospital, where he was held in isolation and closely monitored.

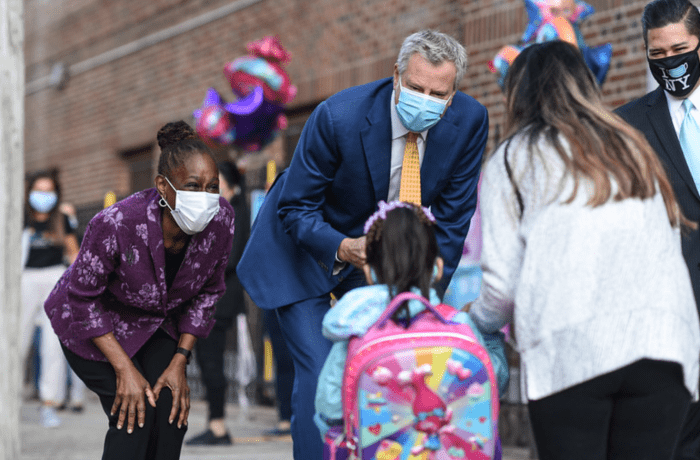

The announcement came as Gov. Andrew Cuomo declared a state of emergency, as the number of COVID-19 cases had continued to grow statewide. Meanwhile, Mayor Bill de Blasio warned that “community spread” was the biggest threat and urged New Yorkers to avoid congested spaces and to stay home if they’re feeling sick.

“This virus is going to give us a real battle. But this virus is no match for the people of New York City,” de Blasio said. “This city is strong. We will get through this together.”

It was the beginning of a nightmare that led to a citywide shutdown to curb the spread of the virus. On March 16, Cuomo had ordered bars and restaurants to shut down, and by March 18, schools were closed. On March 21, he implemented a “stay at home” executive order for all non-essential workers.

Businesses in Queens, such as hair salons, barber shops, gyms and entertainment venues closed their doors. Restaurant owners were allowed to remain open for pickup and take-out services only.

By March 23, the mayor’s office reported there were 13,119 coronavirus patients citywide. Queens had the most cases of any borough, with 3,848.

As the pandemic raged on, hospitals throughout Queens were becoming flooded with COVID-19 patients in their emergency rooms.

For three weeks in March, NYC Health + Hospitals/ Elmhurst in Corona had become the epicenter of the public health crisis. In one 24-hour period, 13 patients died and within days refrigerated trucks were parked outside the facility to handle the dead.

According to Mitchell Katz, president and CEO of Health + Hospitals, Elmhurst Hospital was considered a safe place where immigrants and uninsured people go to receive treatment.

Additionally, Katz had said the high concentration of COVID-19 cases in Queens stemmed from many families living together in close quarters.

“While we are practicing social distancing as a city, you may have multiple families living in a very small apartment,” Katz said. “And so, it’s easy to understand why there’s a lot of transmission of COVID occurring.”

A report from the Citizens’ Committee for Children of New York (CCC), found that those living in areas in higher rates of overcrowded rental housing — more than one person per room — such as Jackson Heights (where 25.7 percent of rental units are overcrowded), and Elmhurst/Corona (25.3 percent) had high rates of positive COVID-19 tests.

The study found that predominantly Black or Latino communities in Queens were affected by the virus; more than half of residents in the western Queens area are Latino, and more than half of residents in southeast Queens are Black.

The study also unveiled that one in five residents in Jackson Heights, Elmhurst and Corona work in hospitality, accommodations and restaurants, while one in five workers in Jamaica, St. Albans and Queens Village work in health care — making all of these residents more vulnerable to catch COVID-19.

As COVID was reaching its peak, hospitals were becoming overburdened with patients and lack of resources — a shortage of personal protective equipment (PPE), ventilators, medical supplies, and staff members were becoming sick with the virus.

To help the city’s straining healthcare system, hundreds of retired nurses, students and graduates were deployed for duty. Additionally, nurses from other states traveled to New York City to work in the hospitals.

In recognition of their tireless dedication to help treat COVID-19 patients, Queens’ healthcare professionals, among other frontline essential workers, were referred to as “heroes.”

The community had shown their appreciation through deliveries of donated meals, letters and residents cheering on essential workers daily at 7 p.m. blasting inspirational music while banging pots and pans.

In Bayside, residents stood outside their homes or on the street at a social distance showing support for local first responders.

“My son is in law enforcement and he’s out there every day, and we have friends that are healthcare workers out there during this pandemic,” said Rita Kashdan, a board member of the Bayside Hills Civic Association. “It’s a very difficult situation right now.”

Since hospital staff were working around the clock, “Fuel the Frontlines,” a Queens-based initiative to feed hospital workers in Queens, had prepared 250 pre-cooked meals that were delivered over the course of a week that began March 29.

The joint initiative was organized by the Queens borough president’s office, Entrepreneur Space, and Queens Night Market. Across the borough, community volunteers were delivering boxes of food to hospitals.

It came during a challenging time when Queens hospitals, most notably Elmhurst Hospital, were facing a surge in the amount of COVID-19 cases coming through their doors. By using local businesses, the initiatives helped small business owners who were struggling to stay afloat during the pandemic.

Meanwhile, hundreds of food insecure families in Queens were lining up outside food pantries, as unemployment rates had soared.

La Jornada Food Pantry, located at 133-36 Roosevelt Ave., which had been feeding thousands of Queens families for years, was put into overdrive since the pandemic hit the borough in March.

Other grassroots organizations helping fight food insecurity include The Connected Chef, Queens Together, Catering for the Homeless, Hungry Monk and Woodbine.

Catholic Charities Brooklyn and Queens hosted emergency food popup events in low-income neighborhoods, while Queens County Farm had partnered with Queens College Knights Table Food Pantry, to help feed students and their families.

The COVID-19 pandemic had devastated Queens’ local economy, the second-largest and most diversified of all the five boroughs, with jobs across the health care, retail trade, manufacturing, construction, transportation, and film and television production sectors. Small businesses act as an important part of the borough’s economic vitality with two-thirds of all businesses employing between one to four people.

In downtown Jamaica, a bustling commercial transportation hub, the streets were silent as businesses were closed, according to Hope Knight, executive director of the Greater Jamaica Development Corporation.

“We never could’ve conceived a situation like this. Some landlords are asking for rent and there have been layoffs of staff,” Knight said.

Small businesses that were depending on the federal government’s bailout plan, known as the Payroll Protection Program, did not receive the first round of funding in April to keep their employees on payroll.

Thomas Grech, president of the Queens Chamber of Commerce, had called for the program to be replenished to provide more federal funding for small businesses, that he said are the “lifeblood of Queens, and communities across America.”

“With unemployment reaching unprecedented levels, and business owners grappling with how to make payroll, pay rent and keep up with other expenses, the time to act is now. We don’t have a moment to waste with inaction or play partisan politics,” Grech said.

However, several establishments in Queens that were considered a staple in their communities had closed permanently due to financial constraints.

In Astoria, the beloved restaurant Queens Comfort closed its doors on Oct. 11 after more than nine years on 30th Avenue. While in Long Island City, Corner Bistro had closed after trying to survive on takeout and delivery service.

Forest Hills’ Austin Street corridor had lost Jack and Nellies, Sushi Yasu, Ren Wen Noodle Factory and the historic Forest Hills Diner. Though the Irish Cottage had closed, it reopened during the summer under new management.

Even though new places were continuing to open, it served as an incredibly challenging time for restaurants, such as American Brass in Long Island City.

The owner, Robert Briskin, had to create a new menu with food, beer and wine, and packages for takeout and delivery, he said.

After a three-month lockdown, Cuomo had given New York City restaurants the green light to offer limited outdoor dining in Phase 2 of reopening, as early as June 22 — two days after the official start of summer.

De Blasio’s “Open Restaurants Plan” included curbside seating by allowing restaurants to convert parking spaces in order to use the roadbed alongside the curb for dine-in service. The city has also allowed restaurants, who are on the city’s Open Streets Initiative, to create areas in front of their establishments.

By June 29, Bayside’s Bell Boulevard was bustling with life once again, as patrons dined beneath the shade awnings and surrounded by custom dividers in order to help put diners at ease while also giving them privacy.

Many business owners had taken the opportunity to create a unique ambiance to the sidewalk, like Chef David Arias, creator of Spanglish NYC, at 4004 Bell Blvd., who designed and decorated wooden frames with an eye-catching urban graffiti style.

“We wanted to make something different to get everyone’s attention. It’s really positive that everybody is now outside. Everybody is trying to get life back again, so we tried to be very creative in the things that we did,” said Charlotte Zubieta, Arias’ mother.

Eventually, indoor dining had reopened at limited capacity capped at 25 percent. However, as the fall season was approaching, there were warnings of a spike in COVID-19 cases, especially during the holiday season.

Then, once again, restaurateurs were hit with a second order on Dec. 14 to close their doors for indoor service, but were permitted to continue outdoor dining and takeout/delivery services.

Cuomo’s decision to suspend indoor dining is a result of sustained increases in the five boroughs’ hospitalization and COVID-19 positivity rates.

Queens Together, a grassroots restaurant advocacy group and food relief organization, had joined several small business leaders across the borough in the last months to call for support.

Jonathan Forgosh, chef and co-founder of Queens Together, suggested immediate solutions such as putting pressure on business interruption insurance companies to respond to restaurants; rent breaks; and freezing punitive fines from state agencies.

For Marcos Munoz, owner of Mojitos in Jackson Heights, the pause on indoor dining is a “very hard blow” not just for restaurant owners, but everyone who is a part of the industry and will be out of work.

Loycent Gordon, owner of Neir’s Tavern in Woodhaven, said restaurants have worked hard to comply with the different kinds of rules and regulations put in place in response to the pandemic and those that were already there.

“Restaurant owners have mostly been complying with rules and regulations and investing in it for the safety of our customers. Our infection rate has been lower than the city average. We’re bringing it down, however we’re being punished,” Gordon said. “This is a death sentence to the citizens we’re supposed to be protecting. This is wrong.”

While the city received its first shipment of Pfizer and BioNTech’s COVID-19 vaccines in December, de Blasio has urged residents and businesses earlier in the week to brace for a possible second shutdown amid a citywide surge in coronavirus cases.

The New York State Restaurant Association is asking for a federal relief package and sent a letter to Cuomo asking for his support, calling the timing “critical.”