As the state is rolling out legal adult-use cannabis with an emphasis on social equity, community boards have been left with a novel responsibility of approving the dispensary applications that are rolling in.

At this month’s monthly meeting that congregates the chairs of all 14 community boards in Queens, a frustration with the state’s lack of support in adopting the new responsibility dominated the meeting. All who spoke up at the Oct. 16 meeting in Kew Gardens expressed a need for more structure to deal with the various challenges that are already coming up in bringing legal dispensaries to communities across Queens.

“There’s no system, we have no guidance,” said Community Board 9 Chair Sherry Algredo, who represents Richmond Hill and Kew Gardens.

The initial goal of the meeting was to give the board chairs a presentation on the workforce and labor laws regarding the cannabis industry in New York. Katie Shane, deputy political director of Local 338, and Cecilia Oyediran, senior outreach associate for the Cannabis Workforce Initiative, were both present at the meeting and shared updates. But the focus of the meeting fell on various issues with the rollout that they acknowledged, but could not do much to address.

Most chairs emphasized that the state was overburdening the volunteer-run community boards, without the guidance needed to take on the new process. After an application comes in, the board is given just 30 days to review applications, make a decision and send any thoughts back to the state, which makes the ultimate decision. But all who spoke up at the meeting agreed that 30 days was far from enough time.

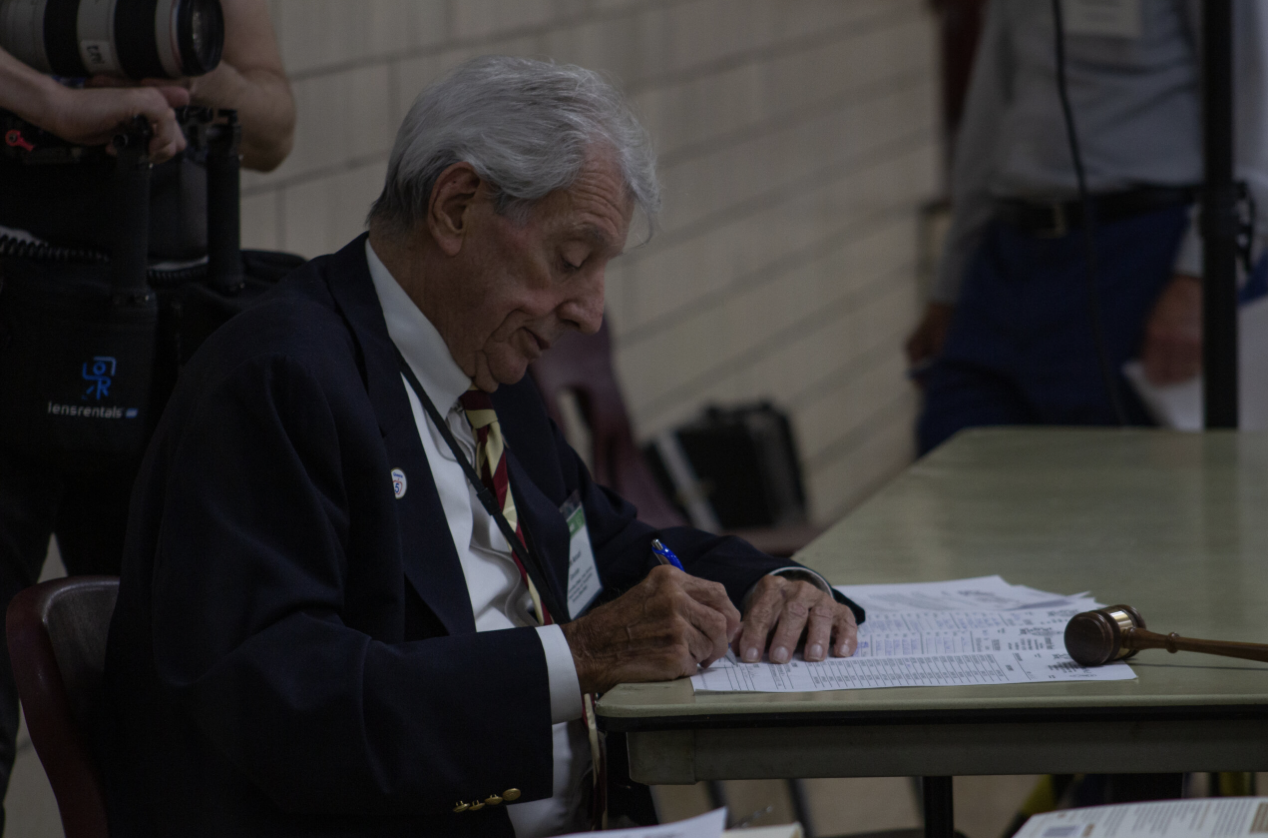

Vincent Arcuri of Community Board 5, which includes Ridgewood and Glendale among other central Queens neighborhoods, said that so far seven applications have come in. Some of them he described as “duplicate people applying for the same location,” which has left the board’s cannabis committee unsure of how to proceed.

“You’re not giving us enough time. We need like three months in order to react to something even if it was one applicant,” said Arcuri, who added that each application deserves to have its own public hearing. “The timing is terrible.”

Typically, community boards approve liquor license applications at the request of new establishments. The process involves cross checking the applicant’s record with the NYPD and giving them a chance to speak at a public hearing meeting. But when it comes to cannabis dispensaries, a clear-cut process has not been laid out yet.

Oyediran and Shane both acknowledged the pressure of the time crunch, and explained that it was a result of the state working to get as many licenses as possible approved to compete with illegal operators.

“It’s sort of unfortunate that the lines of communication with the state and the local community boards haven’t been the best,” said Oyediran. “I hate using the term slow, because we were just really trying to do some innovative things on the social equity front that have led to the delay.”

Dolores Orr, of Community Board 14 in Far Rockaway, mentioned that out of the three applications she’s received, none live in New York City. She questioned if the emphasis on equity extends to local residents, especially when it comes to hiring staff when the storefronts eventually open.

But Orr added that the three applications she received so far were nothing compared to the 72 that one community board in Manhattan received, and the 62 that a community board in the Bronx now has on their plate.

Heather Beers-Dimitriadis, chairperson of Community Board 6 which encompasses Forest Hills and Rego Park, mentioned that they received four applications just last week. She agreed that 30 days was not enough time to make a decision, and that only having a one time extension of another 30 days available is “ridiculous.”

Community boards have also been tasked with measuring if a proposed dispensary is far enough from schools and houses of worship to adhere to regulations. And to make matters more difficult, the applications that do come in have only basic information to help the board make a decision.

“Why is the burden on us to really scrutinize a law and see how many feet it is from a worship place,” Beers-Dimitriadis asked at the meeting. “Is that our job? We’re not clear. Is that our role?”

Marie Torniali, of Community Board 1 in western Queens, said after 13 applications came in, she struggled with deciding between two applicants who applied for a spot 50 feet apart.

Shane suggested that community boards can inquire with applicants about what kind of impact they hope to have on the community. They’re well within their rights to ask applicants what their safety plan is, or even for a mock-up of what the outside would look like. But one chair shared that a recent application failed to provide a phone number with their application.

“You’re asking us to take them at their word. And that’s just not going to get off the ground in our communities,” said Beers-Dimitriadis. “So you’re relying on an agency with the teeny tiniest budget in New York City to be the first line of scrutiny on this.”