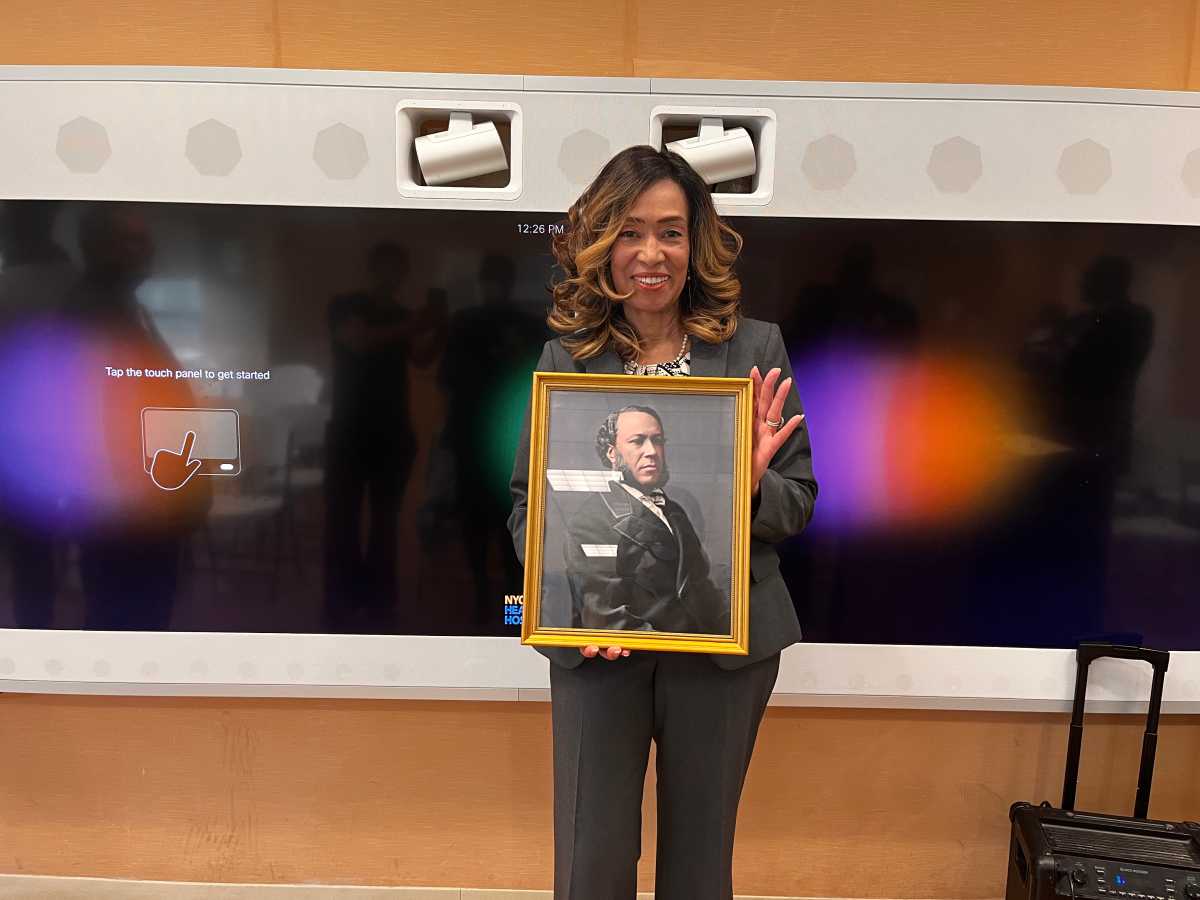

NYC Health + Hospitals/Queens celebrated Black History Month with an informative and inspiring guest speaking engagement on Thursday, Feb. 13.

The event at 82-68 164th St. in Jamaica was led by Lorna Rainey, great-granddaughter of America’s first Black U.S. Rep., the Honorable Joseph H. Rainey (1870). Lorna is a three-decade-long veteran in entertainment, rising to prominence as a certified talent manager (NCOPM).

Although she now lives on Long Island, Lorna recalls growing up in the Southeast Queens neighborhood of Hollis. Lorna shared that she decided to host the NYC Health + Hospital/Queens engagement because of her longstanding personal relationship with the hospital. The author received care from NYC Health + Hospital Queens’ Cancer Center after a breast cancer diagnosis in the mid-2000s and credits the oncology staff for saving her life.

Lorna recalled that she did not have health insurance and needed mammography at the time, so she sought vital imaging at the public hospital. “Although I came here by necessity, now I come here by choice. They found a cancerous lump, and I found the best, most caring, compassionate professionals here. They saved my life and gave me my new beginning; this is the perfect place to celebrate all the possibilities that Queens Hospital Center gifted to me,” Lorna said.

Much of Lorna’s speech centered around her second book—her first historical nonfiction book—“First In the House,” which explores her great-grandfather’s trailblazing legacy from being an enslaved man to a Reconstruction-era firebrand legislator. Lorna is also adapting the senior Rainey’s story into a docuseries to continue highlighting his lifelong legacy to others.

She credits her quest to uncover her great-grandfather’s legacy as being ignited by the stories told by her great-aunt, Joseph’s daughter, Olive. Olive was the first accredited Black schoolteacher in the state of Massachusetts, and every year, she would come to Brooklyn to visit Lorna’s paternal grandmother’s house. “ Each time my dad would drive me to Brooklyn to see Aunt Olive, and at every visit, she would pull me onto my lap and tell me the stories of what her dad had done, and she would always end it with a kiss either on the forehead or on the cheek and say to me, ‘Lorna, you’re going to be the one to tell the world about my father’s achievements,'” Lorna said.

Joseph Rainey was born enslaved to his mother and father, Grossia and Edward, on a rice plantation in South Carolina in 1832. Joseph was the second son of Edward and Grossia, with his older brother being Edward Jr. Lorna explained that Edward Sr. secured his freedom papers for himself and his family with the money he made as an enslaved barber. Edward Sr. was passionate about learning the skill and was permitted by his enslaver to cut the hair of other enslaved men and wealthy plantation owners visiting the plantation.

Lorna explained that it was truly significant and unique to the time that Edward, an enslaved man, could even earn money from barbering.” Strangely enough, by law, the master had to share a portion of his earnings with Edward, and it was in that way that ten years later, he was able to buy freedom for himself, his wife, Edward Jr., and Joseph.” The family then left the plantation and went to Charleston.

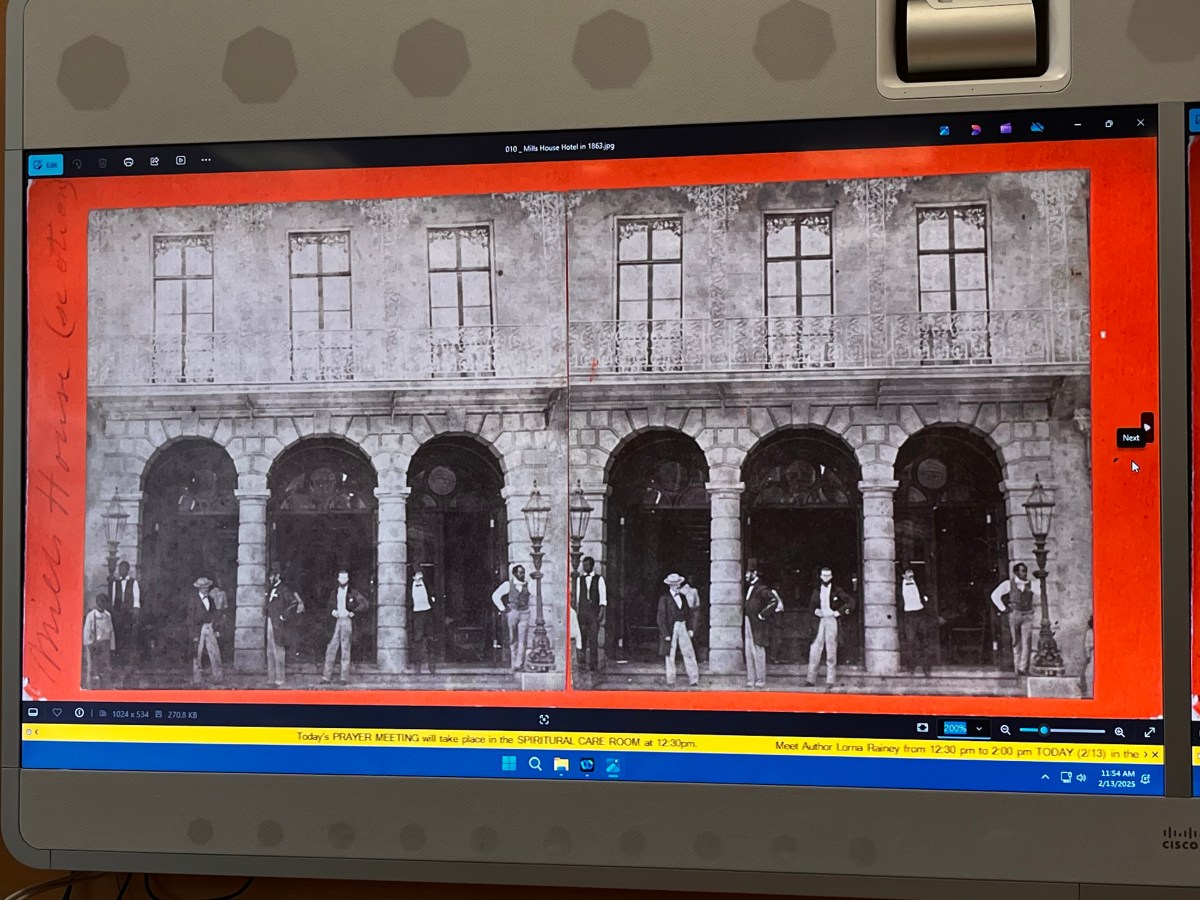

Fast forward, and Edward Sr. got a job as a barber at an upscale hotel, the Mills Hotel in Charleston. “Consider this: in no other profession were the races so intertwined. Think about it: a black man, slave or free, has a razor to the neck of a white man. What type of trust must that have engendered?” Lorna said. Through his earnings, Edward hired private tutors for his children to learn and write, a taboo skill at the time as it was illegal for Black people to learn to read or write. Joseph followed in his father’s footsteps and learned barbering while working with him at the hotel. Eventually, the Reiney family opened their own shop, The Reiney Hair Salon, in Charleston.

At this time, Joseph was an adult and went to Philadelphia to marry his wife, Susan. Joseph was arrested for crossing state lines as it was illegal for Black people to cross the state lines regardless of being a free person. Eventually, he was let out of police custody through a white sponsor.

As the Civil War broke out, Joseph faced the reality that his freedom was potentially jeopardized. Lorna explained that the Confederates picked up every able-bodied Black man, regardless of Freedman status, to work on the fortifications of Charleston Harbor.

An abolitionist friend, along with white allies, helped Joseph escape his arduous physical work with the Confederate Army, and he was eventually smuggled to Bermuda. In Bermuda and the other British Caribbean colonies, slavery had ended 20 years prior, allowing Black people to live freely.

Joseph arrived in Bermuda in 1862 and settled in St. Georges, where he worked at Tucker House and continued his barbering. Tucker House now sits on a street called Barbers Alley, named after Joseph. Lorna said that despite building a strong clientele in Bermuda, the one thing on his mind was his wife Susan, who he had to leave behind in the United States. “Every time there was a boat coming into the harbor, he would go down to meet it, and one day, there she was,” Lorna said.

Together, the couple worked their way into Bermudian society, with Joseph’s success as a barber and Susan as a skilled seamstress. Lorna said that Bermudians admired the couple’s tenacity, helped Joseph develop his reading and writing skills, and gave updates on the news in the States. Joseph’s political involvement began at the Alexandrina Lodge in Bermuda, where he built his reputation as second in command at the lodge.

“By being in this Alexandrina Lodge, he learned the power of politics and organizing, and this is what influenced him and changed history, “ Lorna said. “He saw what was possible for people of color in Bermuda and thought to himself, why can’t this happen for my people back in the United States.”

After some urging from his father, Joseph and Susan were convinced to return to the United States in 1866, which laid the foundation for his congressional career. After returning home, Joseph immediately got involved in politics and business ventures. “ They were coming back to the United States with money, education, and knowledge of how politics and business worked,” Lorna said. “ He also got involved in business, and in January 1870, he and five other Black men got together, pooled their resources, and started the very first Black railway line called the Enterprise Railway. To this day, there has never been another Black-owned railway,” Lorna said.

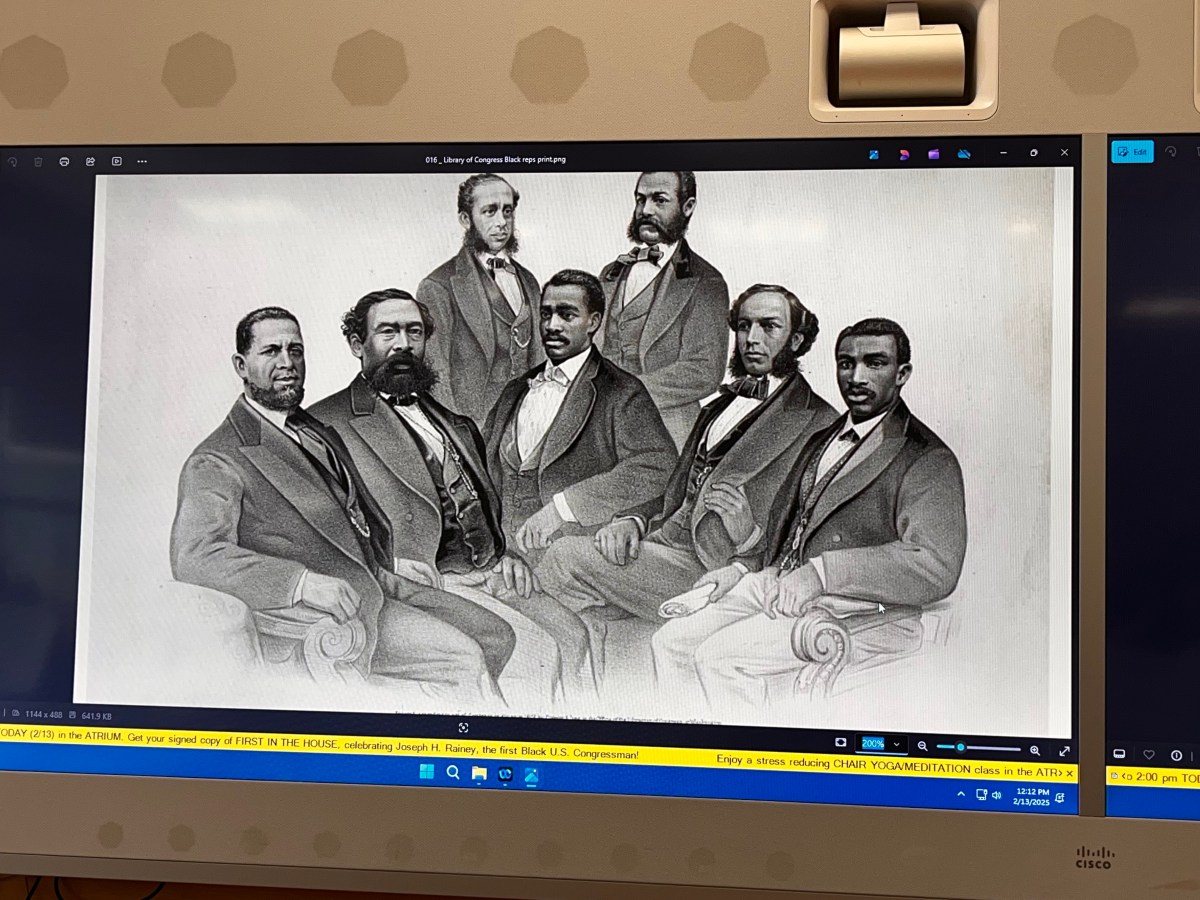

Joseph rose to prominence in local politics, becoming a deglage to the state convention. Eventually, he was nominated and ran to become a South Carolina state senator. After winning his senate seat, he held that position for two years. Joseph was then nominated for a congressional position by his state representatives, and he was approved. “ And on December 12, 1870, he strode into this very chamber, the House of Representatives,” Lorna said. “Because of him, the Republican party in South Carolina grew by leaps and bounds because, at that time, the Republican Party was the inclusive, progressive party that was good for all people, and they asked him, ‘Can you help us?’” Lorna said.

“Can you imagine how he felt when he walked into this chamber, looked around, and he was the only brown face there, out of 230 people, just one person of color? But he was determined to give a voice to the voiceless, hope for the hopeless, and he worked on behalf of all his constituents,” Lorna said. She added that Joseph was particularly concerned about the plight of the Freedmen, as well as Native Americans and exploited Chinese railroad workers.

Lorna described the time after the Confederacy’s defeat in the Civil War as a period of targeted violence against Black people and public officials. Four months after being elected into Congress, in April 1771, Joseph, Senator Charles Sumner, and John Langston drafted the KKK Act, also known as the Enforcement Act, which created a law that made it a federal offense to hinder, molest, or interfere with a public official in a performance of their duties. Hundreds of years later, Lorna said that the KKK Act still has relevance today, as it was invoked to prosecute many of the January 6 insurrectionists.

Joseph Rainey was the longest-serving Black representative until the 1950’s. Lorna explained that due to his activism and firey personality, she feels his legacy was erased from the history books. “But that didn’t happen,” Lorna said. Some monuments and tributes to Rainey include naming a newly built Georgetown post office in his honor. Lorna shared that this naming is significant as there have only been 16 people named after post offices. “It’s so special that you need permission from Congress to do it,” Lorna said.

“These are just a few of the reasons why this man is special. He’s an inspiration to everyone, not just people of color, because it doesn’t matter where you start out; it only matters what you do along the way. He was born a slave—how much lower in life can you be than that—yet he rose to become the first Black Congressman,” Lorna said.