A century ago, the land at Woodhaven Boulevard and Myrtle Avenue was a dump heap and an eyesore. It sat just north of the Woodhaven Reservoir and had been used as an unofficial garbage dump for many years. Locals complained and asked that it be cleaned up and turned into something useful, but their pleas went unanswered.

However, in the wake of the First World War, the public was keen to see tributes to honor the young men who went off to fight and never came home. In Woodhaven and Richmond Hill, Memorial Trees were planted in the names of the dead, and the trees were decorated every Memorial Day.

But with the pain of the war still fresh, local residents called for something more substantial and permanent. And so, in the spring of 1925, Queens Parks Commissioner Albert C. Benninger unveiled plans to transform this “dump and an eyesore” into a state-of-the-art athletic facility.

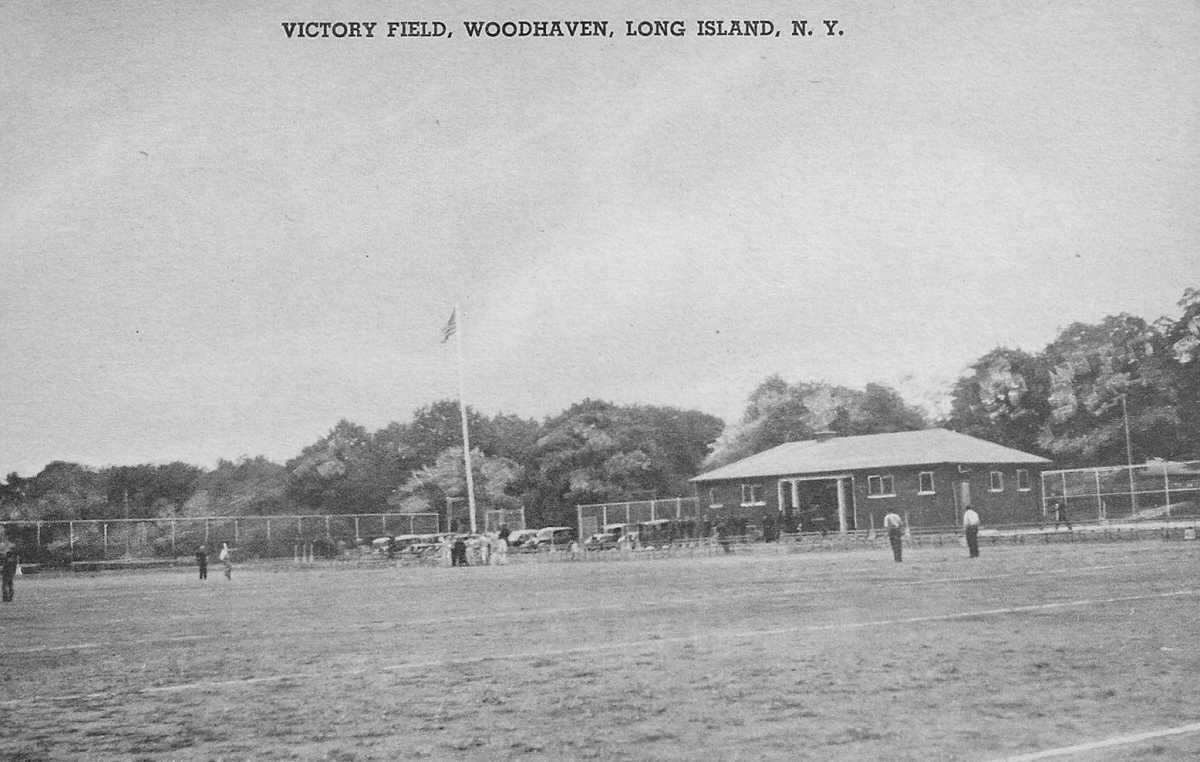

The site would include a four-lane quarter-mile track, six baseball diamonds that could also be used for football, basketball courts and handball courts, all for a cost of $100,000, which would be roughly $1.8 million today.

As the brand-new park neared completion, Commissioner Benninger announced that it would be named Victory Field in honor of the Unknown Soldier of the World War from Woodhaven and Richmond Hill.

James Pasta, the first commander of American Legion Post 118 in Woodhaven, was placed in charge of the committee overseeing the development of the site and planning the ceremonies. The American Legion had been formed nationally in 1919 to serve veterans and their families, and over 30 posts were taking part in the opening ceremonies, which were scheduled for Sunday, Dec. 6, 1925.

Several thousand people, old and young, came out to tour the new sporting arena and watch the dedication. Joining the American Legion posts were the Veterans of Foreign Wars and Spanish-American War Veterans, as well as local members of the Grand Army of the Republic, whose members fought in the Civil War. Imagine that—veterans from the United States Civil War marching around the track at Victory Field.

The Rev. Andrew Magill of the First Presbyterian Church of Woodhaven eulogized the boys from Woodhaven and Richmond Hill. “We hope that this and all other war memorials will remind people of the horror of war and make them steadfast in their efforts toward world peace in the future,” he said.

In front of a quiet crowd, a squad of eight men from American Legion Joseph B. Garity Post No. 562 fired a triple salute into the air. That was followed by Taps, performed by bugler Arthur Skinner, who had served as bugler for General Pershing in France. Across the field, another bugler answered Skinner’s solemn notes.

After the dedication, there were several races, with the highlight being world champion athlete Willie Plant attempting to break a record by walking eight miles in under one hour. However, the dedication ceremonies lasted so long that five and a half miles into Plant’s attempt, it was too dark for the judges to see him, and the attempt was called off.

That winter, and for many winters afterward, the Parks Department would fill one of the fields with water, and once it froze, it became a popular spot for ice skaters. Hundreds of people would skate on Victory Field, huddling around nearby fires for warmth.

Victory Field stands today, 100 years after it was dedicated, as a lasting memorial to the young men of Woodhaven, Richmond Hill and Glendale who perished in World War I. In 2007, the track at Victory Field was named in honor of former Assemblyman and Judge Frederick D. Schmidt. And in October of this year, the baseball field at Victory Field was named in honor of Detective Brian Simonsen of the 102nd Precinct, who died in the line of duty in 2019.

Victory Field is more than just a park. It is a living monument that has evolved with the community while preserving its original purpose: to honor sacrifice and service while remembering the hope for peace that inspired its creation a century ago.