With homeownership at half of what it is compared to the rest of the country, a new proposal has been submitted to make housing more affordable for low-income New York City residents.

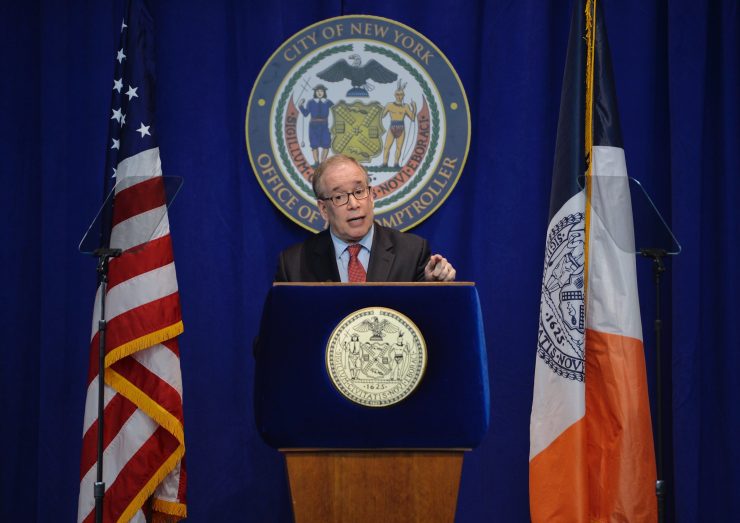

On Jan. 29, New York City Comptroller Scott M. Stringer announced a five-borough housing strategy. The strategy, called Housing We Need, aims to realign New York City’s approach to the housing crisis, including establishing a universal requirement for 25 percent permanently low-income affordable housing in all new as-of-right development with 10 or more units.

The plan also calls for the end of the 421-a tax subsidy program for developers, which costs the city more than $1.6 billion per year, as well as the expansion of affordable homeownership programs, the redirection of existing capital dollars to extremely and very low-income housing construction, and the creation of a New York City land bank that would facilitate the process of turning vacant city-owned properties into affordable housing.

“The power in this approach lies in its simplicity: If you’re going to build in New York City, you will provide affordability that is sustainable,” said Stringer. “You will be part of the solution. No longer will developers be able to use affordable housing as a bargaining chip with communities.”

An analysis by the Comptroller’s Office found that the “affordable” housing created by “Housing New York” is too expensive for as many as 435,000 of the city’s most severely rent-burdened households. Of the newly constructed housing in the 2019 fiscal year, only one third of the units available reached the extremely low and very low-income households. Additionally, the analysis found that nearly 565,000 New York households pay over half of their income for rent, are severely overcrowded, or have been in homeless shelter for over a year. Most of the housing built under the city’s Housing New York plan, according to the analysis, is set at 80 percent of HUD-defined Area Median Income (AMI), or households making up to approximately $77,000 a year, or higher.

With most of the housing being unaffordable for local residents, Stringer’s plan is to bring universal housing would be set at an average of 60 percent of AMI (household income of $58,000 a year for a family of three), or two parents making minimum wage and raising a child. Additionally, 10 or more units across New York City will be legally required to set aside at least 25 percent of its units or the floor area, whichever is greater, for permanent low-income affordable housing.

“This is the housing that helps families that are one paycheck away from losing their homes,” said Stringer. “This is the housing that gets New Yorkers out of shelters. This is the housing that empowers folks to climb the economic ladder to security and stability. This is the housing we need.”

According to the Department of Finance, the current 421-a program, also known as Affordable Housing New York, is currently the largest subsidy that generates affordable housing with an annual cost of $1.6 billion in foregone property tax revenues. However, the units that were created do not stay affordable and can rent for as much as $3,100 a month.

Stringer’s plan would put an end to 421-a by providing subsidies on a discretionary basis strictly to fill in financing gaps where there is demonstrated, documented need in order to meet the new mandate for affordability, deepen the affordability levels, increase the amount of affordability or provide good-paying jobs. The city would give more discretion to tailor subsidies including property tax abatements and capital subsidies, however it would be mandated that the affordable housing that is build remain permanently affordable.

Finally, Stringer’s plan to increase homeownership across the city will includes expanding the Department of Housing Preservation & Development’s Homefirst and Homefix programs to provide qualified moderate- and middle-income homeowners with up to $40,000 toward down payments and loans for home repairs and waiving real property transfer and mortgage recording taxes for qualified first-time homebuyers. Tenants would also be granted the right of first refusal to buy their buildings should their building go up for sale or foreclosure, as well as leveraging banks and land trusts to build affordable co-ops and condominiums on city-owned land, and building more limited equity housing for middle-class families.

“If we’re going to allow more New Yorkers to climb the economic ladder, and to thrive in communities they’ve lived in for years, we need a bold new approach to housing,” said Afua Atta-Mensah, Esq. Executive Director, Community Voices Heard. “Comptroller Stringer’s plan is a paradigm shift — it will ensure new affordable housing is actually affordable to the most vulnerable New Yorkers and that all communities have skin in the game. This is the housing we need across the five boroughs.”