By Lisa Autz

Far Rockaway’s Beachside Bungalows have been given a guardian by the name of Richard George.

The historic beach homes, from Beach 24th to Beach 26th streets, have been surviving against waterfront developers and hurricanes with the help of George, president of the Beachside Bungalow Preservation Association and 30-year area resident, who has a dedication to the bungalows that has not yet met its match.

The job of a preservationist never takes a break for George, as he is fixated on conserving the remains of the shrinking seaside neighborhood. Now only about 100 bungalows exist from the once-thriving vacation spot that held more than 7,000 in the 1920s.

“I saw the importance of preserving a part of not only Rockaway’s cultural legacy associated with the past recreational resources of our coastal area, but also a part of Rockaway and America’s history of the early 20th century,” he said.

Along with helping to get the Beach Bungalow Historic District on the State and National Register of Historic Places, George has invested long hours in a span of about 20 years suing against projects in the district that violate zoning codes and coastal policies. These actions have resulted in zoning revisions of almost the entire Rockaway peninsula to secure the bungalows’ ocean views and public access to the beach. The owners of the oceanfront homes now hope to gain city landmark status to further preserve the distinct character of the community.

“The State and National Register protects against government development. We are hoping to get New York City landmark status, which would require developers to go through the commissioner to make changes,” said George.

In the 1920s, during the construction of Cross Bay Boulevard and the Far Rockaway boardwalk, bungalow real estate was booming. Working-class Jewish and Irish immigrants flocked from the hot, congested city to a summer home near the shore. The beach cottages made up the city’s only oceanfront community at that time.

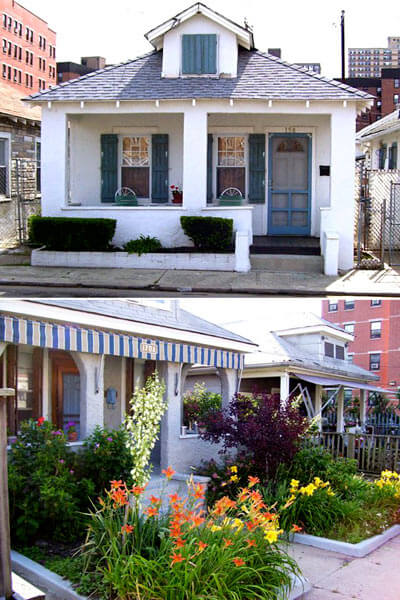

The distinct architecture of the one-story cottages was the work of Henry Hohauser, designer of art deco hotels in Miami in the 1930s. Each is made of brick and plaster and features two to three bedrooms, a small kitchen, bathroom and an open front porch. The endangered few that remain represent the once-flourishing vacation neighborhood where working-class families congregated.

For the time being, George has filed more than seven lawsuits against city developers using the Defense of the Coastal Zone Management Act of 1971, a federal act devoted to preserving beachfront access for public use. He has sued major companies such as YOMA development group, Impressive Homes and Metroplex on the Atlantic. The federal appeals court, however, has repeatedly told George he has no standing to sue, since Congress does not give rights to individuals or citizens in the coastal zone statute.

“The judge ruled contrary to the law,” said George, who explains the federal judge refused to acknowledge that the act states citizens, along with local government and state agencies, have grounds to ensure there is compliance with its policies.

The Corona native has lived in the urban waterfront area since 1981. After working in the city doing antique porcelain restoration for wealthy clientele, George retreated to the bungalows of Far Rockaway where his mother resided. Now as owner of two bungalows, one as his home and one has his restored art studio, George takes pride in his dedication and claims it is a product of his roots.

“My family origins are from Italy, where they preserve structure and art. I was hired to do antique porcelain restoration of fine antiques from China, England, France and realized the value in preserving parts of culture and history over the centuries,” George said.

After joining the Beachside Bungalow Preservation Association in 1981, he was voted onto the board in 1985 and has since become president. George’s environmental initiatives as a member of the BBPA have contributed to the bungalow community’s survival through Hurricane Sandy.

After a $15,000 grant from the JM Kaplan Fund in 1992, George, along with several volunteers, planted beach grass, shrubs and other salt-tolerant plants along the boardwalk from Beach 24th to Beach 27th streets. As a result, the heavy-rooted grass and shrubs developed a double-dune system that formed a barrier against erosion and destruction during the storm.

Environmental organizations took notice of the community’s inexpensive natural defense and featured them in Happold Consulting’s Sandy Success Stories of New York and New Jersey in June.

New York Happold Consulting, an international engineering consulting firm, teamed up with city civic organizations and reached out to the Real Estate Board of New York as well as the American Society of Landscape Architects to investigate small-scale solutions against storm damage.

Environmental groups working with the firm produced 20 case studies of preventive measures, one of which was George’s beach grass dune system.

The more palpable threats to bungalow survival, however, are still being argued before the city Landmarks Preservation Commission. In May, George sent a letter to Mark Siberman, general counsel of the commission, requesting revisions of city zoning resolutions and the building code to further comply with waterfront revitalization policies and establish the bungalows as city landmarks.

Still waiting for a response, George and the BBPA organized a meeting with the Department of City Planning March 19, listing requested changes and outlining the BBPA’s overall goal: to collaborate with the city Zoning Resolution and Building Code to preserve the bungalow district from towering developments that block ocean views, public access to the beach and disrupt the character of the community.

The written requests ask for a joint effort between private and public sectors to work together in achieving the goals of the BBPA for further survival of the community.

“I have narrowly described the requirements and work very hard for any change,” said George.

The resilient preservationist has spent long hours studying coastal and zoning laws as a self-appointed lawyer in the majority of his lawsuits. His gritty character may be the vital ingredient in preserving the historical bungalow community.