This unprecedented year brought unprecedented change to the largest school system in the country — from an initial shutdown some said took too long to call, a delayed reopening in the fall, and new challenges for students, parents and school staff alike to grapple with.

In early March, after the first COVID-19 case in New York City was reported at the end of February and the first in Queens at the beginning of March, some private schools began to close out of precaution of the outbreak.

Educators, parents and elected officials then began to call for all public schools to close, in order to get a better handle of the novel coronavirus. However, childcare and meals became a big concern, as working families depended on the school system to ensure their children not only have two steady meals per day, but also have a safe place to be while they’re at work.

Queens City Councilmen Francisco Moya and Robert Holden joined Speaker Corey Johnson and Brooklyn Councilman Mark Treyger in urging the city to instead just have schools provide families with free meals.

“Kids absorb everything. They see the stores around them closing, sports events getting canceled, their families scrambling to make last-minute arrangements,” Moya said. “Despite this, we expect them to set everything aside when they arrive at school as if it exists in a vacuum, separate from what’s beyond the classroom window. That’s not an environment for academic success and it’s not an environment that will keep them safe from the COVID-19 pandemic.”

Shortly after, in an emergency address, Mayor Bill de Blasio announced the “painful decision” to close the city’s public school system, which serves 1.1 million students. Attempts to reopen schools during the spring semester were in vain, though, as the city and state struggled to keep up with the virus inundating the hospital system.

Schools Chancellor Richard Carranza noted families could pick up daily free meals at designated schools and the city’s 75,000 teachers would undergo intensive training to begin instructing students remotely.

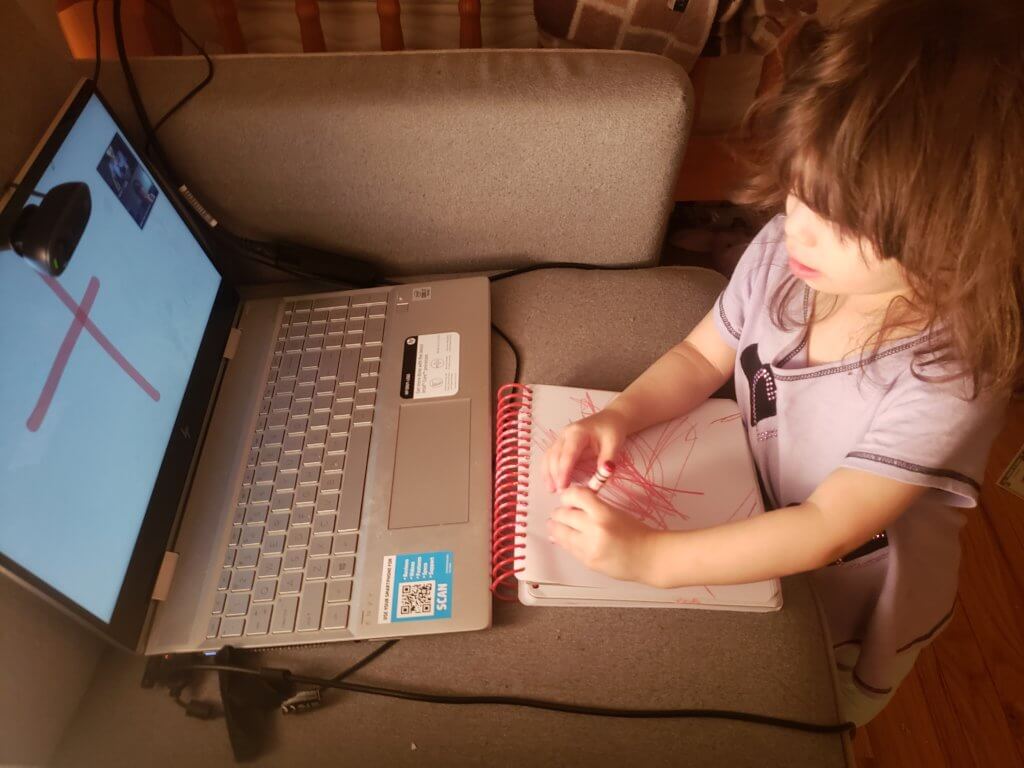

But with the new structure came new challenges, namely internet and tech access.

The Department of Education (DOE) initially set out to deliver 25,000 iPads, with an ultimate goal of 300,000, with internet capabilities to students in need. Some internet providers, like Spectrum, offered free WiFi for a few months — but they were soon met with criticism as some families with unpaid bills couldn’t access it, according to Chalkbeat. They later provided the service for low-income families for a certain period of time.

All throughout, school-aged children tried to adjust to the abrupt shift.

“I feel sad I cannot see my friends,” Jordan Turkoglu, a first-grader at P.S. 290Q, said at the time. “I have some school work but it’s not a lot and I feel sad I cannot see my teacher. I’m happy because I saw some of my friends on video yesterday. I do want to play with my friends but now I cannot.”

Parents, most of whom found themselves working from home for the first time, also had to adjust to having their children home all day, every day. Some felt they had to become their children’s teachers.

One Astoria mother and entrepreneur, Tamykah Anthony, who homeschooled her two children long before COVID-19, gave QNS a breakdown of what a day in her life teaching her children and running her own businesses looked like, with the hopes of encouraging parents to be patient with themselves as they navigate the switch to remote learning.

For students with special needs, teletherapy became the default. But that meant parents who normally relied on educators and therapists for their children became overwhelmed and concerned of regression in their development, as a Forest Hills mother with a daughter with autism told QNS.

The height of the pandemic caused many New Yorkers to feel hopeless as cases and deaths surged, while people’s everyday life underwent abrupt changes in order to fend off even more heartache.

But there were bright moments sprinkled along the darkness, and acts of kindness became more of the norm. Teachers stepped up to the challenges ahead, with some recognized for their efforts to bring joy and lighthearted fun to their students, such as Andrea Feldman, teacher at I.S. 145Q in Jackson Heights, and Tom Carty, principal of P.S./I.S. 49 in Middle Village, who sang to their students to keep them motivated.

“Our kids are probably going through a mix of emotions from being worried, curious, scared and nervous about what lies ahead,” said Feldman. “If my silly songs and jokes can help put a smile on their faces and get through this, that’s the most important thing to me.”

To respond to childcare needs, the DOE established more than 100 Regional Enrichment Centers (REC) where children of emergency and essential workers could stay during the COVID-19 health crisis.

In Queens, one of those RECs was located at P.S./I.S. 128 in Middle Village. Chancellor Carranza and first lady Chirlane McCray paid a visit to the facility in June, which gave a first look at what schools may look like once buildings reopened — children and staff wore masks all day, they had to get their temperature checked at the door, and indicators were placed on the floor and desks to maintain six feet distance.

As COVID cases decreased and Gov. Andrew Cuomo’s re-opening plan ensued — bringing back temporarily dormant jobs and businesses — parents and educators anxiously waited to hear a plan for the city’s new public school.

De Blasio and Carranza introduced their plan, which included random COVID tests for students and school staff as well as two different learning models: blended learning, a mix of in-person and fully remote school days, or fully remote learning. The city promised 100,000 childcare seats for students in blended learning, with less than 30,000 of those seats slated to open by the beginning of the school year. Meanwhile, Catholic schools in Brooklyn and Queens mostly prepared for in-person learning.

But in the weeks before the original start to the school year in September, teachers and school staff across the city and Queens — some protests took place in Jackson Heights and Bayside — called for a delay in reopening school buildings, with safety and staff shortages as their main concerns.

After negotiations with the United Federation of Teachers (UFT), the mayor announced that schools would open in phases and provide more safety measures for each school community.

Students were still getting into the groove of the new way of learning, many missing in-person learning and activities. But some found creative ways to get kids out into their communities, such as Maspeth High School’s “Maspeth Making a Difference” club in which students helped clean up their surrounding neighborhood.

But blended learning came with some confusion for some Queens parents. In October, parents at P.S.128 protested over what they said was a lack of live instruction and clear communication from the school.

“Why didn’t they organize this better? Be truthful to the parents,” one parent, who is an essential worker and asked to remain anonymous, told QNS at the time. “If you decided blended, the rest of the week your child would not have a live instruction. Explain it first, then we could have organized this differently.”

A DOE spokesperson said the school was working on getting the needed staff to ramp up live instruction.

More than 335,000 families have opted into blended learning after the city’s second opt-in period in November. Opt-in periods were originally meant to take place in a quarterly basis, but that plan was scratched after the city reported lower than expected in-person class enrollment and attendance.

But as a second wave threatened to fully shut down schools once again, de Blasio announced schools would close for two weeks prior to the Thanksgiving holiday. While many parents argued the closure, the decision was based on the city reaching a 3 percent infection rate, a threshold previously negotiated with the UFT to ensure school safety.

More than 800 schools returned to in-person learning in the second week of December, with the DOE establishing more weekly COVID testing and a map of schools that is updated on a weekly basis, showcasing the buildings and classrooms that have closed due to COVID cases. Just a few days after schools reopened, nine schools in Queens were closed again due to COVID cases.

The city later announced a new plan to address the “COVID achievement gap” for public school students, and rolled out plans to overhaul the admissions process for the upcoming school year, including the elimination of screenings for middle school students, among other changes.

With two COVID-19 vaccines now approved by the FDA and their distribution currently underway as COVID infection rates and hospitalizations see a resurgence, there is no telling what other transformations New York City’s school system will undergo in 2021.