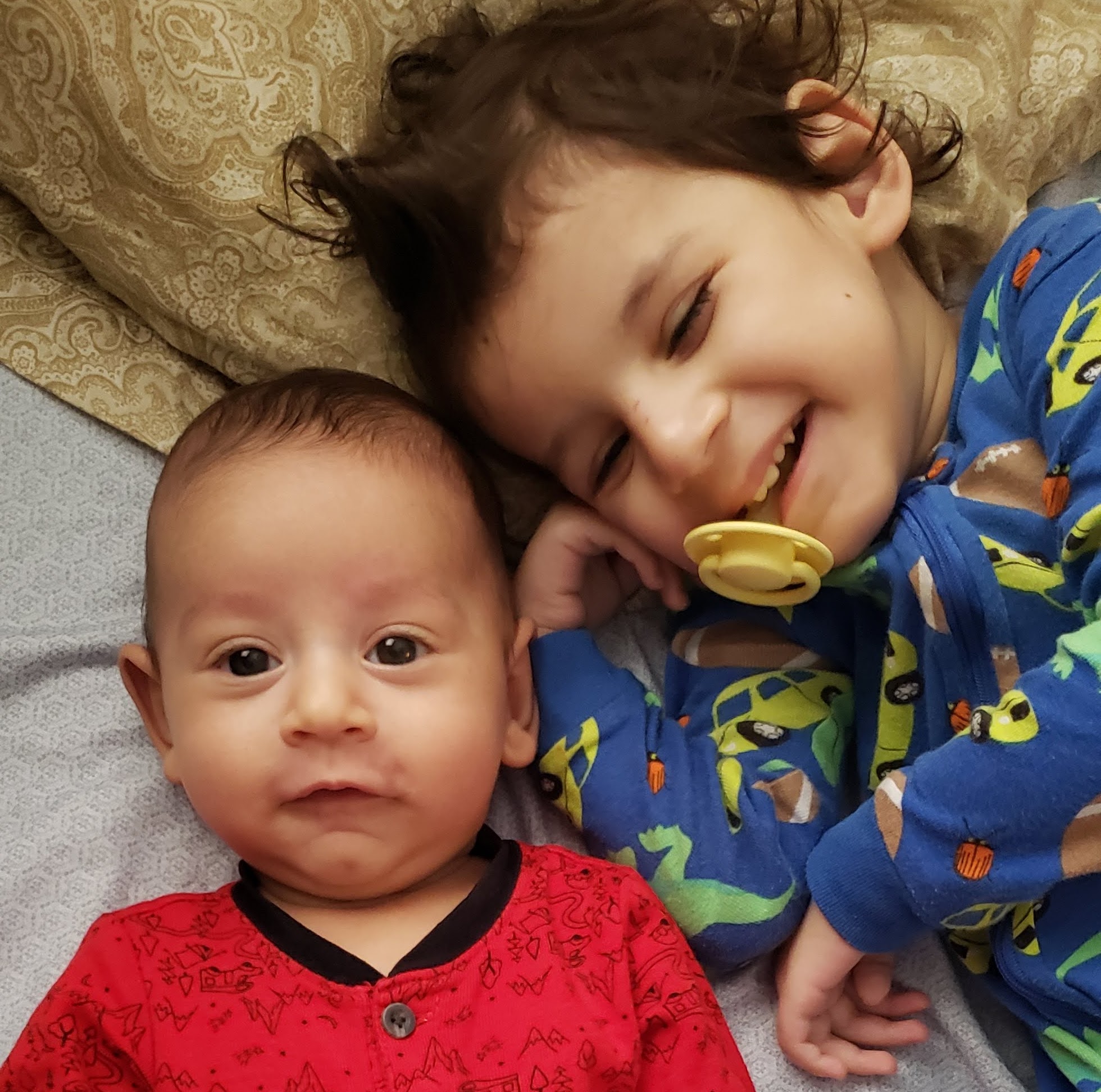

In March 2021, when Gurjot “Jo” Kaur and Richard DiGeorge of Oakland Gardens found out their 15-month-old son, Riaan, was diagnosed with Cockayne Syndrome, they had no idea it would be a diagnosis of a rare, fatal neurodegenerative disease which has no cure.

“We felt like we were trapped in this horrible storm with no way out,” Kaur said.

Cockayne Syndrome is a rare genetic disorder characterized by short stature, an abnormally small head and neurologic abnormalities that can lead to intellectual disability, according to the National Organization for Rare Disorders.

Children diagnosed with CS may also have skin that is sensitive to light; inflammation of peripheral nerves and destruction of the fatty covering of nerve fibers; vision abnormalities including cataracts, hearing loss; dental abnormalities and a face with a sunken appearance of the eyes.

Like so many parents who have children with a rare disease, Kaur and DiGeorge took action to help advance critical research into the disease by founding The Riaan Research Initiative .

“Everyone told us ‘Sorry, there’s no treatment, there’s nothing that can be done,’” Kaur said. “It wasn’t until we shared our story publicly, that we got connected with other advocacy groups and scientists who said there are things you can do. We learned that it’s not about finding a cure, it’s about funding a cure.”

The Riaan Research Initiative is dedicated to promoting and furthering translational scientific research to advance treatments for severe and life-limiting genetic disorders, according to the website. It aims to identify and facilitate projects to improve the lives of patients suffering from genetic conditions lacking approved therapies.

Kaur and DiGeorge started the initiative shortly after Riaan was diagnosed with Cockayne Syndrome Type II, the most severe type, with an average life expectancy of five years. While it has been a long journey for the family of four, Riaan celebrated his third birthday in December. He is stable, happy and progressing, his parents said.

“Riaan is a ball of energy. He loves playing soccer. He uses a walker, also known as a gait trainer, and when he got that freedom he was a little apprehensive at first but then he realized that he can do all of the things he wants to do,” DiGeorge said. “His smile is contagious. His laugh is contagious. Regardless of all the things going on with him, he’s always smiling and enjoying every bit of life he has.”

As they have a limited time window to work with due to the disease’s rapid progression, the couple said they’re working hard to get treatments developed as quickly as they can and to raise money to get it done.

Desperate to find a cure for their son, Kaur and DiGeorge entered an agreement with UMASS Chan Medical School in 2021 to support research into Cockayne Syndrome. Earlier this month, the couple was thrilled to hear that progress has been made as researchers at UMASS achieved a major breakthrough in developing an adeno-associated virus (AAV) vector gene replacement therapy in mice models with Cockayne Syndrome.

Kaur and DiGeorge are optimistic that the research team’s findings could one day treat children and adults with the disease.

“We are so happy that this is a huge milestone they have reached, which has never been done before,” Kaur said. “They have successfully treated mice with severe conditions of the disease with the same mutations Riaan and other children have.”

Ana Rita Batista, PhD, instructor in neurology, is leading the research, along with Miguel Sena-Esteves, PhD, associate professor of neurology and director of the Translational Institute for Molecular Therapeutics.

“Cockayne is caused by mutations in potentially two different genes that are in the DNA repair pathways, CSA or CSB. Our work is focusing on finding treatments for the CSA of Cockayne Syndrome patients,” Batista said.

Their goal, according to Batista, is ultimately to move toward clinical trials to treat people and help them improve their lives. The research team reported that in initial studies they have extended the lifespan of the animal models, which resumed normal growth after treatment.

For Batista, the journey has been both great and scary at the same time, she said.

“I’m always reminded there’s a family and a little kid on the other side of this, and it puts a little bit more pressure on our shoulders dealing with mice everyday,” Batista said. “There’s so many things we can learn from reading the books and the people studying this disease. Then you have Jo who lives with this everyday with her kid and she tells us certain things, and we say, ‘Oh, maybe we should do this in our mice models and treat those symptoms.’”

Sena-Esteves noted the importance of partnering with a foundation to fund research into finding a cure for rare diseases.

“Research takes quite a lot of money. Without the foundation it’s impossible to do it because at least to start working on a disease we need some funding,” Sena-Esteves said. “The difficulty is raising money for diseases that the majority of people have never heard about. It’s very hard work on the foundation’s side and the parents work relentlessly to raise money, so we’re always very conscious of how the money is spent.”

Before starting the Riaan Research Initiative, Kaur and DiGeorge said they never thought that parents would have a role in getting treatments developed for diseases.

“We do in fact have a critical role. Not only are we funding this work, we’re also raising awareness and helping to accelerate the project in a way that wouldn’t be done if it weren’t for Riaan’s situation and the situation of our community and the advocacy that our organization is doing,” Kaur said. “Drug development can take years and decades. The critical role that parents play and the community helping to donate to organizations like ours is changing the game. We’re actually making a big difference.”

Kaur and DiGeorge are seeking support from donors to make it to the finish line to raise $4 million. To donate, visit https://riaanresearch.org/