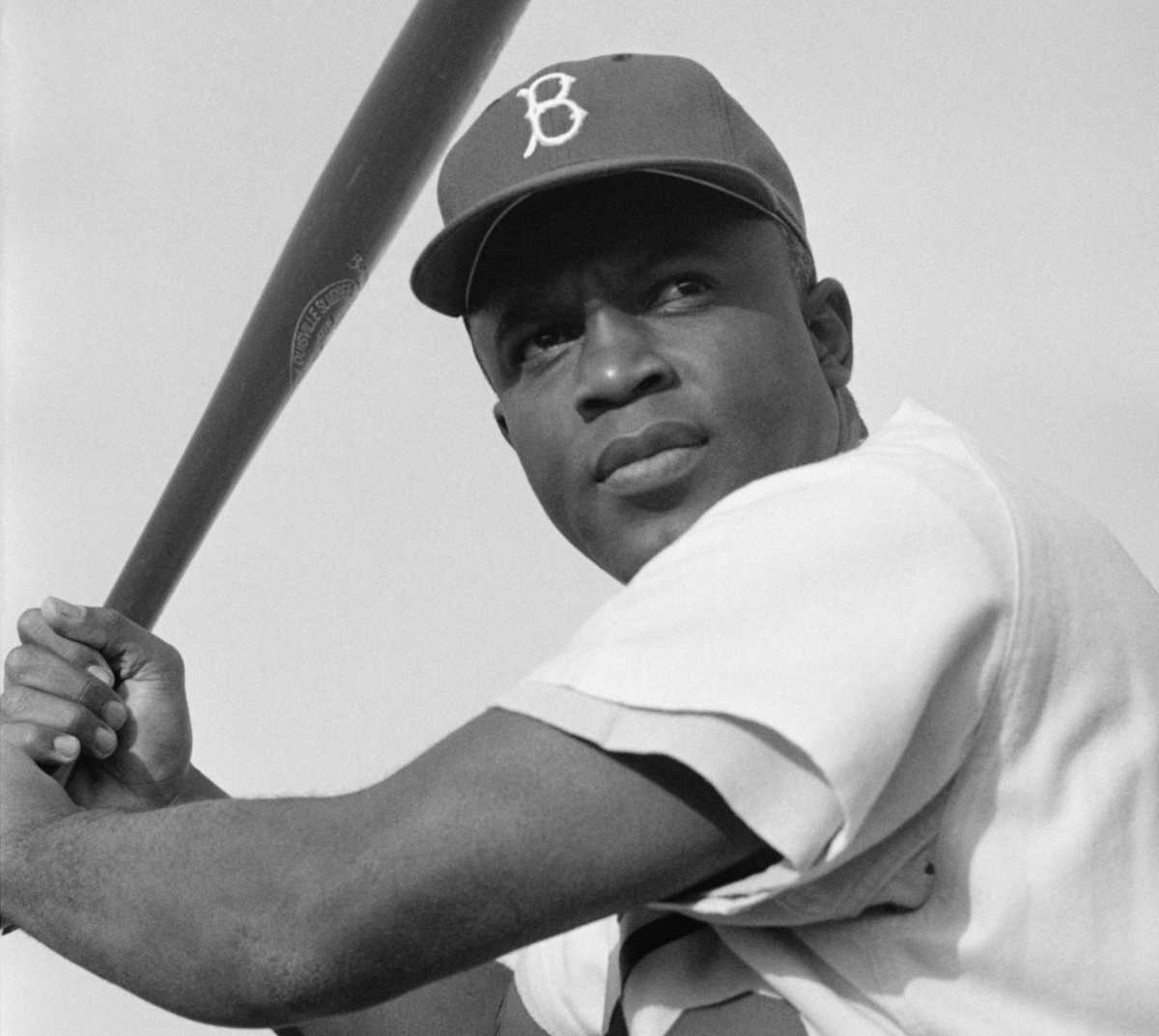

One of the most transformative figures in American history, Jackie Robinson did more than break baseball’s color barrier. He helped bring the nation a few steps closer toward achieving the “more perfect union” that our Constitution decreed, yet struggles to fulfill even today.

Most Queens residents know that Robinson’s memory lives on in two prominent Queens landmarks: the Jackie Robinson (nee Interboro) Parkway linking Queens to Brooklyn and the Jackie Robinson Rotunda, the grand entrance to Citi Field, home of the New York Mets in Flushing.

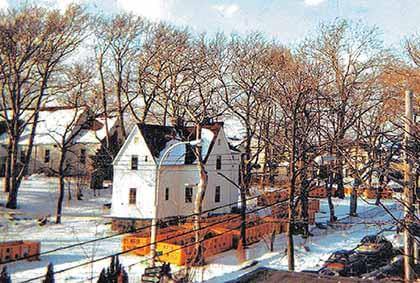

Few may realize, however, that Robinson lived for a time in our borough, specifically the Addisleigh Park section of St. Albans. Two years after joining the Brooklyn Dodgers, Robinson and his family moved there in 1949, buying a home located at 112-40 177th St., in the middle of the now-landmarked community.

Like Robinson, Addisleigh Park has a place in civil rights history — though dubious at the beginning. The suburban neighborhood was developed in the early years of the 20th century, but each single-family home built there included deed restrictions which mandated that only white people could purchase them. Those same restrictions prohibited white homeowners in the neighborhood from selling their homes to Black buyers.

The segregation lasted for several decades, but in the end, justice would prevail. In the 1930s, white Addisleigh Park homeowners sold their residences to prominent African-American entertainers based in New York, including Count Basie, Ella Fitzgerald and Herbert Mills. Some Addisleigh Park neighbors filed lawsuits that the segregational deed restrictions had been broken; their lawsuits, however, ultimately failed, and the cause of progress and equality prevailed.

Robinson moved to Addisleigh Park in 1949, a year after the Supreme Court ruled that racially restrictive deed clauses violated the 14th Amendment of the U.S. Constitution. With his wife, Rachel, and their children, the Robinson family would remain there through 1955 — the same year that Jackie helped the Brooklyn Dodgers win their first and only World Championship.

“We used it to move on to the next stage of our lives,” Rachel Robinson recalled in a 2008 interview with the New York Daily News. “We had moved around and hadn’t been sure of anything — whether Jack would make it with the Dodgers, or if we could ever afford a home.”

The Daily News article notes that the Robinsons purchased their Addisleigh Park home for $100 and other considerations, as outlined in the deed. They loved the neighborhood so much that they managed to convince Roy Campanella, Jackie Robinson’s teammate and star catcher for the Dodgers, to purchase a home there as well.

The Dodgers, of course, left for Los Angeles following the 1957 season; Jackie Robinson, who had been traded to the also-relocating Giants, refused to go west and subsequently retired. After leaving Queens in 1955, the Robinsons headed to the suburbs just outside of Stamford, CT.

For the rest of his life, Robinson would remain active in the civil rights movement nationwide, advocating for an end to segregation while also founding businesses to improve the lives of African-Americans across the country.

After his death in October 1972, Robinson returned to Brooklyn and was laid to rest in Cypress Hills Cemetery, which straddles the Brooklyn/Queens border. He’s interred there alongside his son, Jackie Jr. — who preceded his father in death by a year — and his mother-in-law.

A short distance away is the road once called the Interboro Parkway, which leads drivers from the Grand Central Parkway in Kew Gardens Hills through Forest Hills, Glendale and Ridgewood into Brooklyn. The city renamed the parkway in honor of Jackie Robinson in 1997, one of many tributes that year commemorating the 50th anniversary of Robinson breaking baseball’s color barrier.

Etched on Robinson’s tombstone is his most famous quote: “A life is not important except in the impact it has on other lives.” That quote also lines the top of the Jackie Robinson Rotunda at Citi Field, which honors his legacy in baseball and American life. Citi Field, of course, opened in 2009 as the New York Mets’ new home, replacing Shea Stadium; it was constructed in much the same style as Ebbets Field, the old Brooklyn Dodgers’ home.

In the rotunda, you’ll also find a large form of the number 42, Robinson’s uniform number with the Dodgers, which was universally retired by Major League Baseball in 1997. Every major league player, however, wears 42 in games played on April 15 every season.

Share your history with us by emailing editorial@ridgewoodtimes.com (subject: Our Neighborhood: The Way it Was) or write to The Old Timer, ℅ Ridgewood Times, 38-15 Bell Blvd., Bayside, NY 11361. Any mailed pictures will be carefully returned to you upon request.