Residents of the Pomonok Houses public housing project say quality of life in the cluster of buildings they call home has decreased substantially since the mid-1990s, when a law was passed that effectively ended the careful screening process that once controlled who was given apartments.

A 1992 court ruling designed to help housing developments citywide become more ethnically diversecoupled with a 1995 ruling that prevents developments with populations that are over 30% white from taking in their share of poor working familieshas resulted in Pomonok receiving more new residents from homeless shelters, according to local Assemblywoman Nettie Mayersohn (D-Fresh Meadows).

"It used to be beautiful here," said Sharon Butler, a slender African-American woman who has lived in the project for 11 years. "Now the crime rate is going up." She and the three other women she was standing with on one of the projects winding paths agree that its because new residents are not being properly screened for admittance.

"A man on my floor is harassing me," she continued. One of Butlers friends, who declined to give her name, nodded in agreement. "Our floor has a lot of kids," the woman said. "Theyre mostly girls. Everybodys scared of him."

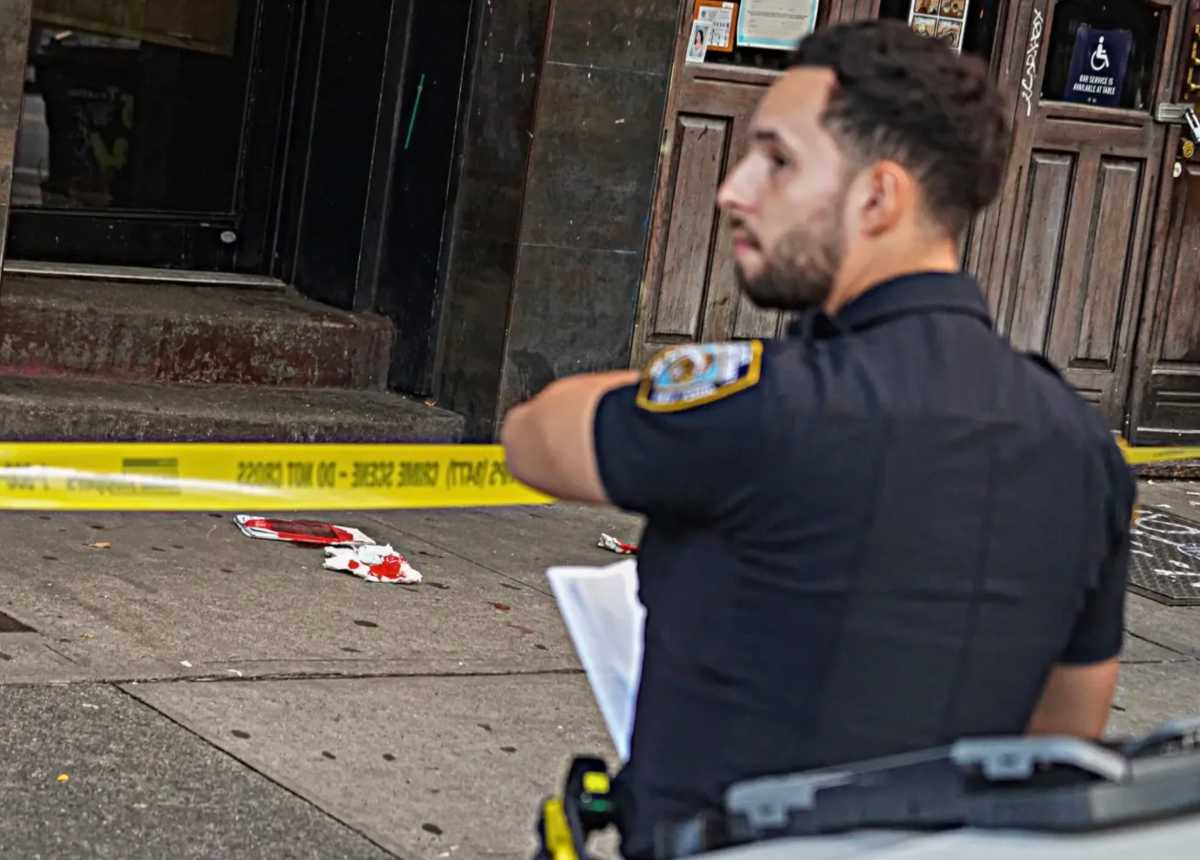

Up the path, 16-year-old Shadai stood with her two younger cousins. She said her 19-year-old brother had been shot and killed in the project just a month before. "It used to be nice here," she said, and then turned to her cousins. "I dont think they should grow up here."

In another part of the development Mary Lou Arroyo and Maggie Hamilton were watching their children in a playground.

"I got a letter from my kids school saying a convicted sex offender lives here," she said. "A lot of people who used to be in prison are here, too. That didnt used to happen." Hamilton agreed. Both said they thought things had gotten much worse because of the lack of an effective screening process for admissions.

"This was once the jewel of the New York City Housing Authority (NYCHA)," said Teresa Alleva, president of the Pomonok Residents Association, Inc. "But if we dont control it now that will not be the case anymore."

The downturn in quality of life at Pomonok has its roots in well-intentioned legislation. A 1992 lawsuit accusing NYCHA of assigning people to housing developments based on their race resulted in a ruling that created a new system for those designations. Prior to the ruling, the population in Pomonok was predominantly white. The integration process was initially successful, and members of a variety of ethnic groups moved in. However, a 1995 court decision created a new system by which working families were given preference for apartments in public housing, but developments that were more than 30% white could not access the working families list. According to Mayersohn, that ruling led Pomonok to be given more than its share of homeless and unemployed people, as Pomonok is still about 38% white.

"Certainly we accept our share of homeless," said Mayersohn. "But its important to have a balance. To have a development made up of mostly unemployed people is dysfunctional." Mayersohn was quick to say that Pomonoks issues had nothing to do with race. "Many on the working families preference list are minorities," she explained, adding that Pomonok would like the chance to bring them in. She also said that many working families are on Pomonoks waiting list, but that Pomonok could not accept most of them because of the ruling.

NYCHA spokesman Howard Marder said that NYCHA had appealed the ruling several times, and even took it to the US Supreme Court. However, in June of this year the Supreme Court declined to hear the case and now nothing more can be done. "We believe the working families preference is a good thing," said Marder, adding that it is the percentage rule that NYCHA disagrees with.

As for Sharon Butler and her friends, they are considering moving out. "We dont object to people on public assistance," one of Butlers friends said. "They just need to screen better."