Alan Walowitz

Nicole (Lucivero) Martini never met her grandfather Nick for whom she is named. Her brother Nicholas never met him either.

Their father, also Nicholas Lucivero, never met his father, Nick, who had died six months before he was born. Her cousin, Anthony Maraglino, never met his grandfather, Nick Lucivero, either.

Rose Esposito, Nick Lucivero’s sister, remembers her brother as a war hero who landed on Normandy Beach in June 1944 — a great athlete, a guy who lit up a room when he came in.

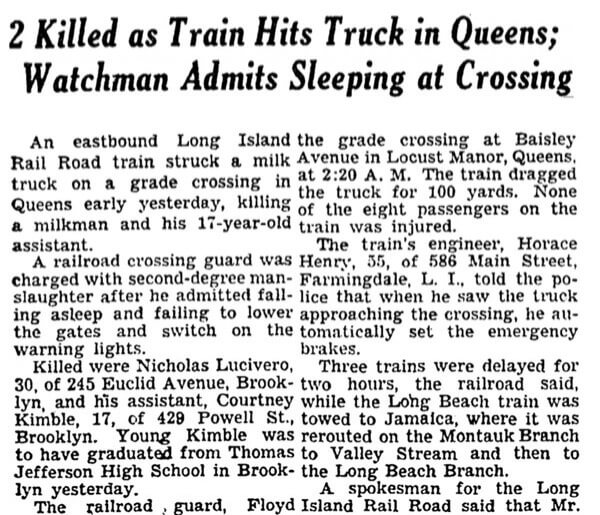

She has told all her family’s young the stories about her brother, Nick, who died 60 years ago on Jan. 30, 1957 in a tragic accident at the Locust Manor Station near Farmers and Baisley boulevards in St. Albans when his milk delivery truck was hit by a Long Beach-bound Long Island Rail Road train.

The watchman had fallen asleep in the early morning hours and failed to lower the gate to stop the oncoming milk truck, driven by Nick Lucivero. The milkman was accompanied by his assistant, Courtney Kimble, who was 17 and just about to graduate from high school.

I was in third grade, not quite 8 years old, the morning this happened—and Nick Lucivero was my milkman. For all I know, he might have been on his way to deliver milk to my house in Cambria Heights, a little more than 2 1/2 miles away.

I might have met Nick once or twice, though I can’t say for sure. After all, milkmen were denizens of a nocturnal world a kid wouldn’t know much about.

But hearing about the death of our milkman shook my world. Kids in middle-class Cambria Heights were pretty sheltered in our neighborhood with neat lawns and sturdy houses on tree-lined blocks. Our fathers had fought in the war and didn’t like to talk about it much.

Our mothers mostly didn’t work outside the home and were there when we walked home for lunch and at 3 o’clock when school let out.

Things went wrong, of course, but nothing had ever happened as tragically and unexpectedly as this, and never so close to home.

Yeah, I was an overprotected, sensitive kid who was disproportionately affected by such things; I spent a lot of time living inside my own head; I even grew up to be a poet.

But the story of the death of the milkman haunted me and has stayed with me my whole life. Enough so that I wrote a poem about the event.

The poem is called “The Story of the Milkman” and Melanie Villines, the publisher of Silver Birch Press, was kind enough to publish it on her website in 2015.

A year and a half later, Anthony Maraglino was doing some Internet research on his family and he hoped to find more information about his larger-than-life grandfather who he had only heard about and never met.

In the course of doing that research he found a reference to a poem called “The Story of the Milkman.”

He traced it to the Silver Birch Press website and found the poem I had written. Along with the poem I included a paragraph which told the “true” story of Nick Lucivero, at least as true as far as I could piece it together.

Anthony passed the poem on to his family, including to his cousin Nicole and his Aunt Rosie. Anthony also found me on Facebook and sent me a message telling me of his connection to the poem and how reading it had moved him. Shortly after, I was notified by Melanie Villanes, the publisher of Silver Birch, that there was a new comment posted about “The Story of the Milkman,” this one written by the milkman’s sister, Rose Esposito, who is now in her 80s and who had experienced this tragedy firsthand, and who remembered her brother so lovingly.

Then, I was contacted by Stephen Blackburne, a friend of Nicole (Lucivero) Martini. Stephen had purchased a copy of my book, “Exactly Like Love,”(Osedax Press, 2016) in which the poem also appears. He asked me to autograph the book so he could give it to Nicole as a gift.

Soon I heard directly from Nicole, who told me how much reading the poem and having a copy of the book meant to her. In her email, she wrote, “Thank you also for writing your poem – my father, who will be 60 in June, never met his father. The accident occurred six months before he was born.

This poem has given us all reason to talk about my grandfather and has, in just a few short weeks, allowed my father to come to terms with things he hasn’t thought about in 40 plus years.”

I can’t know exactly what Nicole means, and frankly it’s none of my business. But I do know this: Most regular folks—and good folks they are, too—don’t much care for poetry. Marianne Moore confessed in her famous poem titled “Poetry” that she too disliked it. When pressed, people often say they don’t understand it.

They usually blame a high school English teacher and, as a retired high school English teacher, I’ll even accept some of the blame.

Others like to quote the poet W.H. Auden who said, “Poetry makes nothing happen,” this perhaps a way to explain their preference for an editorial that angers them, for a touching and well-written obituary, or a good love story.

But “The Story of the Milkman,” my poem, actually made something happen.

Perhaps it’s not a big thing, unless you consider connecting with some strangers, and helping them connect with their own pasts over the distance of nearly 60 years to be something. I think it is.

——

The Story of the Milkman

When I was a kid our milkman was killed

right before dawn at a railroad crossing

one low whistle away from where we lived.

We read about it in the Mirror

and were in awe seeing Nick,

a man we’d actually met,

right there with the wife and kids he left,

inset with a picture of the wreck.

At bottom, a separate shot,

was the watchman, bleary and ashamed,

as he was led from the scene.

We grabbed our bikes and tore to the crossing,

but it was mostly cleaned up

except the street was closed

and if you wanted to cross

you had to ride all the way over to Farmers.

We just wanted to look.

Later, my father took us there in the car

and made a noise like a train coming through;

I dug my nails in my palms,

and wished Nick were my dad.

That’s how strange crossings are:

you want the train to come

and kind of hope it won’t.

I can’t even see Nick’s face anymore,

which I had memorized like a list of spelling words.

Or my father’s, which I forgot to study at all.

The next week there was another milkman.

Then my father was gone

and I was a father.

What I hold onto most is that milk box

as if I owned it still

and Nick was going to fill it

with quarts of glistening glass.

Made of galvanized tin,

mottled from the weather,

you could barely make out the name

“Sheffield’s” stenciled in red,

and on the hottest day of summer

it was so cold inside

you wished you could crawl in and hide

from whatever was confusing you to death,

or scaring you sick.