Primary and special elections will never be the same with ranked-choice voting going into effect in 2021.

With primary elections serving as the deciding factor in Democrat-heavy New York City, the change to voting is going to be important.

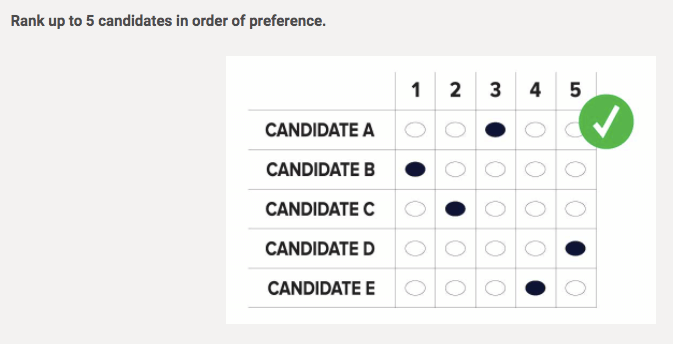

Not only will voters in the five boroughs be dealing with a new a ballot format that allows them to rank their top five candidates from most to least favorite, residents will have their work cut out for them in deciding since some districts have dozens of candidates running.

The district represented by Councilman Costa Constantinides for example has up to 12 candidates while Councilman Jimmy Van Bramer’s district will get to choose from 19 individuals.

What will the ballot look like?

Ballots will allow voters to rank their choices one through five. However, if they wish to simply only vote for one candidate and leave the rest of the bubbles blank, they can do that.

If none of the candidates get by with a 50 percent majority, the candidate with the least first rank votes is eliminated and second choice votes on the eliminated ballot are counted as first rank votes. If a candidate then passes the 50 percent threshold, they are named the winner. If not, the processes repeats until a winner is determined.

Voters’ ballots will be eliminated if they choose the same candidate for all five ranks. Additionally, a ballot will be deemed invalid if a voter gives multiple candidates their top rank, according to the city Campaign Finance Board.

The first election that will use ranked-choice voting will be on Feb. 2, a special election to fill the void left by former Councilman Rory Lancman when he resigned in September to work for Governor Andrew Cuomo.

What are some obstacles to ranked-choice voting?

Ranked-choice voting itself was adopted by voters in 2019 under a referendum that was designed to prevent runoff elections. But nonetheless, questions of educating the public on the new system have been endemic with the City Council debating in December whether or not to postpone the rollout until outreach has been made more effective.

“The idea of ranked-choice voting was to create a system that didn’t require a runoff. And some argued it, you know, would engage people more. Others said it wouldn’t, but, you know, the people did vote for it in a referendum,” Mayor Bill de Blasio said in early December. “But when you hear community leaders saying, look, we’re not getting the education we need, we have a major election in six months and people don’t know how to use this yet, that’s a cause for real concern.”

After presenting their concerns about ranked-choice voting in February 2020 some elected officials argued that with the lack of educational outreach on the new ballot system would put New Yorkers who are not proficient in English at a disadvantage, and in December, launched a lawsuit to block the plan.

The state supreme court rejected the bid to put off ranked-choice voting.