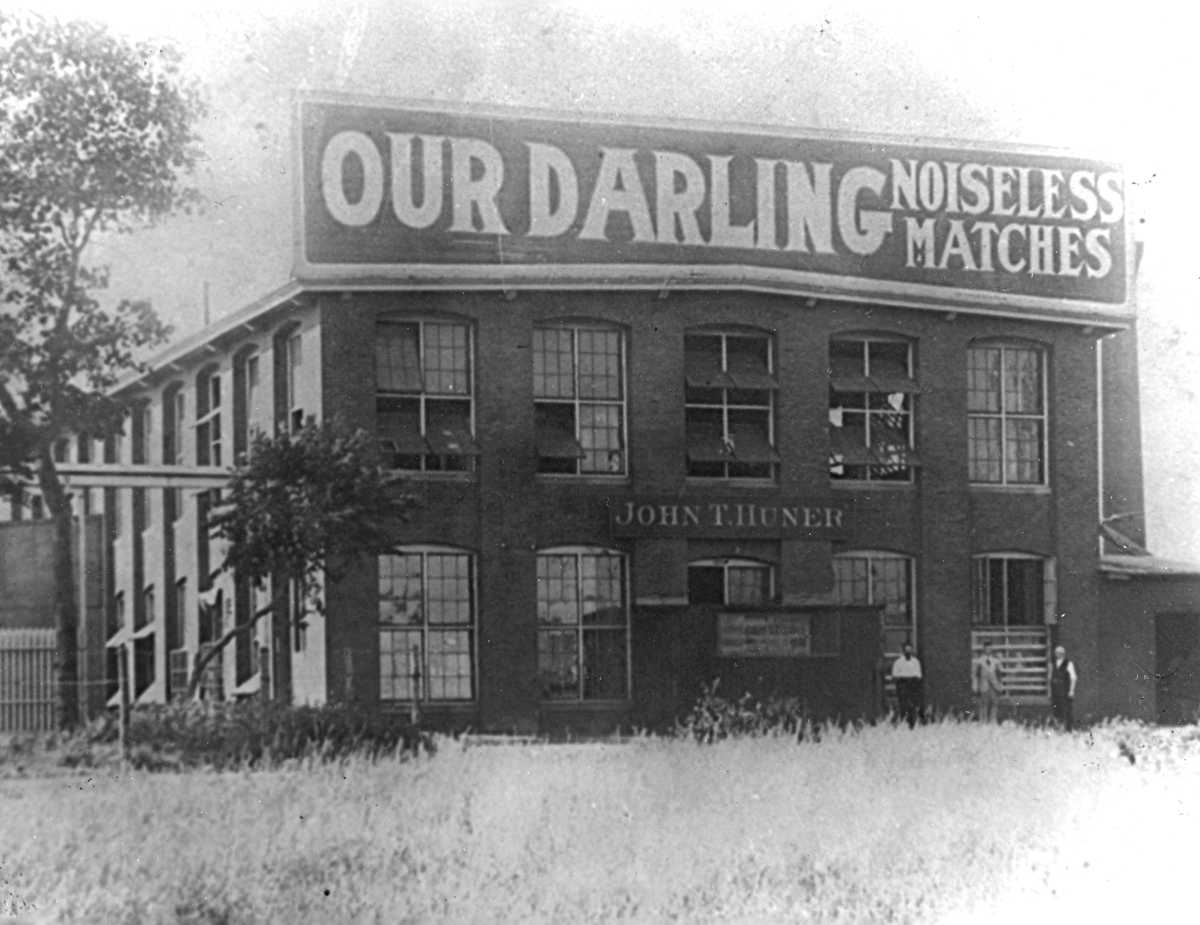

In May 1904, John T. Huner of Hancock Street in Brooklyn opened a match factory in what was then called Evergreen, located in present-day Glendale at the corner of Myrtle Avenue and Centre Avenue (later called Charlotte Place and now called 60th Lane).

The Our Darling match factory produced both wooden strike matches and paper safety matches. Railroad freight cars on the nearby Bay Ridge line of the Long Island Rail Road delivered loads of white pine which was die cut into small pieces suitable for matches.

Wooden strike matches (also called friction matches) were first produced in the U.S. in 1836 when Alonzo Phillips of Springfield, Massachusetts, was granted a patent to make matches using white phosphorus. This was a poisonous, flammable chemical that was luminous in the dark.

Workers in match factories were susceptible to necrosis of the jaw, also known as “phossy jaw.” Rats were also attracted to the white phosphorus and chewed on the match heads, causing fires. Young children also suffered poisoning by putting match heads into their mouths, and the chemical was used in many suicides and homicides.

Safety matches were paper matches designed to light only when struck on a specially prepared match. They were invented by Joshua Pussey in 1892 and eventually, for most uses, replaced wooden strike matches.

In 1896, one of the large breweries ordered 10 million packets of paper safety matches to advertise their beer. This was the start of volume production.

The original Our Darling Match Factory was a two-story brick building with connecting wooden one-story buildings. The wooden buildings were covered with zinc plating as a protective measure. The finished matches and the chemicals were stored in the wooden buildings.

Just to the north, adjacent to the railroad, was a tall smokestack for the power plant.

In the early 1900s, most of the match production in the U.S. was controlled by the Match Trust, which set production rates and prices. Huner did not belong to the Match Trust and fought them bitterly.

The Match Trust packaged their wooden strike matches in boxes of 500, which were sold by grocers for 5 cents. John Huner packaged his wooden strike matches in boxes of 1,000, which were sold at 5 cents, thus undercutting the Match Trust.

Making a safer match

In June 1910, the Diamond Match Company of St. Louis, Missouri, a member of the Match Trust, announced that they had developed a harmless substitute for white phosphorus. Early in 1911, William Fairburn, who worked for the Diamond Match Company, was granted a patent. He had succeeded in modifying red phosphorus to U.S. climatic conditions and thus developed a safer match, as it raised the ignition temperature more than 100 degrees Fahrenheit.

The less poisonous match was less flammable, and not as luminous in the dark.

To eliminate their competitors, the Match Trust went to Congress and lobbied for legislation placing a prohibitive tax on matches made with white phosphorous.

On Jan. 20, 1911, Huner went to Washington, D.C., and testified before the House Ways and Means Committee. He stated that the Match Trust was pushing this legislation to put the Our Darling Match Factory and other companies out of business. Several days later, The New York Times ran an editorial stating that a number of workers in match factories had become ill working with poisonous chemicals, and if Huner could not afford to improve his plant, he should shut down.

To resolve the matter, President William Howard Taft asked the Diamond Match Company to license the free use of their patent. The company agreed to do so, and Huner accordingly changed his matches to red phosphorus.

Factory up in flames

But the next year, on July 26, 1912, a fire broke out at the Our Darling Match Factory. A pile of paper matches fell over, and enough friction was produced to ignite them.

Robert Woods, 17, of 23 Cypress St. was working at a machine nearby with his back to the fire. He felt an increase in warmth, and when he put his hand on his back, discovered that his shirt was on fire.

He tried to put the fire out, but quickly saw that he could not. He ran through the plant, sounding the alarm, and then ran out the door. He trotted all the way to German Hospital (today known as Wyckoff Heights Medical Center) on St. Nicholas Avenue and Stockholm Street. He was treated for burns on his face and hands.

The big factory whistle sounded at 1 p.m. As the flames spread, there was a mad scramble by the 300 workers at Our Darling to get out of the building.

Mary Reiss of 210 South 19th St. in Williamsburg, Brooklyn, was in charge of a department of 16 girls in the west end of the building. They were literally blown off the floor and windows by the draft created by the flames. In the east end of the building, 41 girls in another department rushed out in a panic. Some of the workers on the ground floor jumped out of the windows; fortunately, all of them escaped.

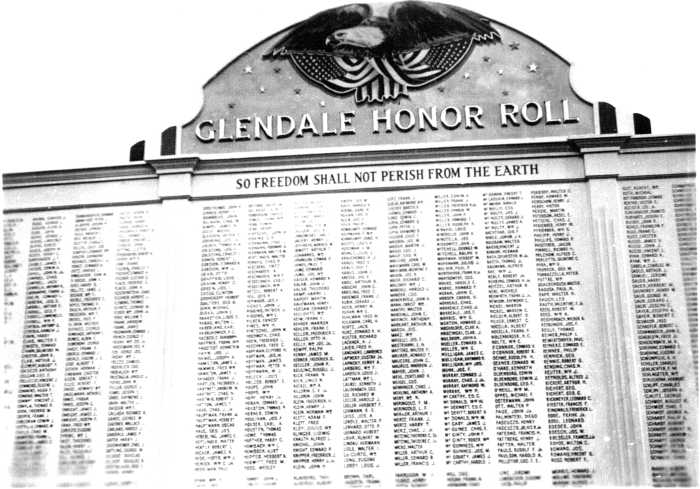

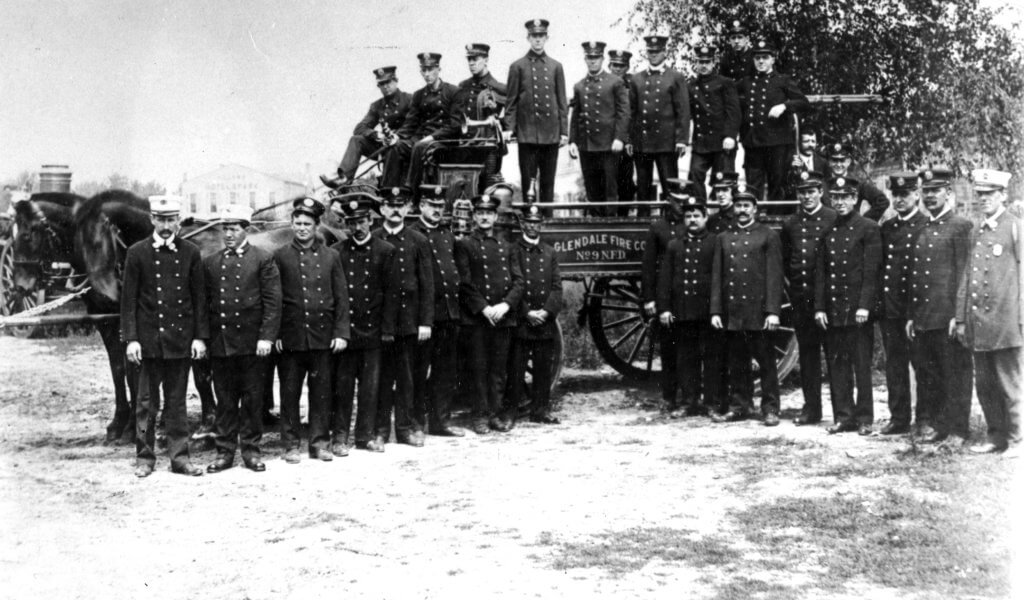

Companies 9 and 10 of the Newtown Township Volunteer Fire Department responded to the alarm, and when they arrived and saw how serious the fire was, they put in a second alarm. This brought out Newtown Volunteer Companies 4, 7, 12 and 13. They also telephoned the New York City Fire Department, which agreed to send three companies from the closest firehouses in Brooklyn. These, like the volunteer companies, were horse drawn.

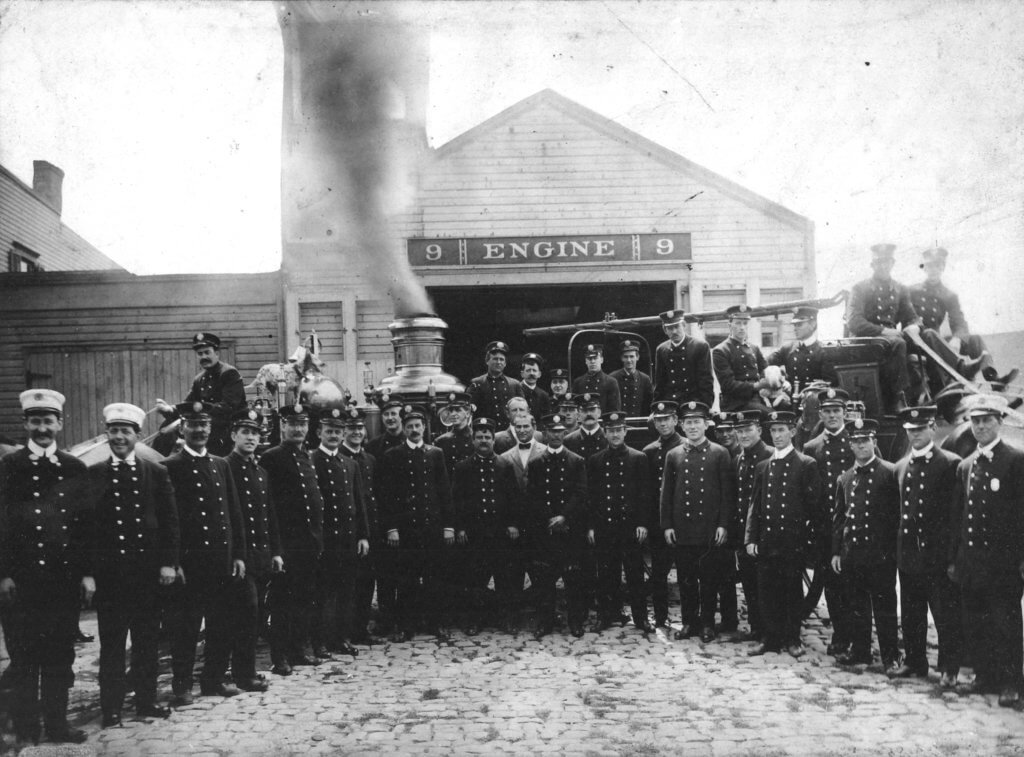

Company 9 was Glendale Hook and Ladder Company, located on the south side of Myrtle and Cooper avenues on what is today a McDonald’s. The company had 40 men with a steam engine pumper pulled by three horses, and a hose cart pulled by two horses.

Company 10 was the Ivanhoe Hook and Ladder Company located on Fresh Pond Road south of Myrtle Avenue. Company 12 was the Metropolitan Engine Company located on the south side of Metropolitan Avenue near Forest Avenue, and Company 13 was the Glendale Park Hook and Ladder Company located on the south side of Myrtle Avenue between Martin Avenue (presently 88th Place) and Oceanview Avenue (present-day 88th Lane).

Although the fire departments exerted their best efforts, the main building was totally destroyed with damage estimated at $200,000. Huner had insurance on the building, but not on the expensive machinery and inventory of supplies and matches.

The fire was one of the largest the neighborhood had ever seen.

Business burns out

The morning after the fire, Huner announced that he would commence construction immediately on a new one-story concrete building that would be bigger than the original Our Darling factory. He also had a crew of workers trying to salvage some of the machinery and also sorting out the matches that were stored in the outbuildings. Some of them had burned from the intense heat, and others had not.

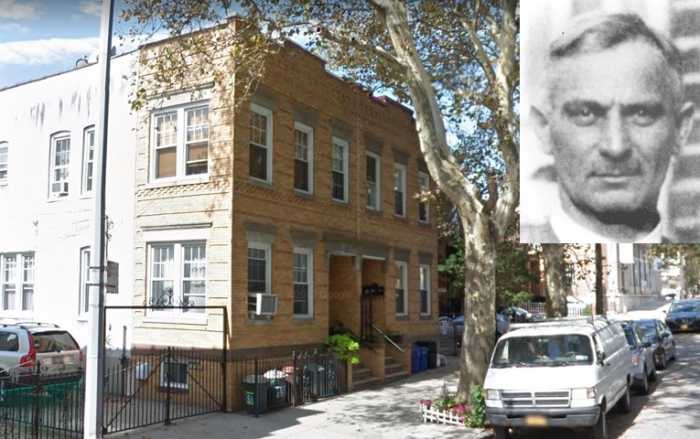

Huner died suddenly on Dec. 24, 1912, at his home in Brooklyn. He was 56 years old at the time, and his two sons, who were active in the business with him, continued to operate the company.

Our Darling Match Company continued in business until 1923, when it became the Liberty Match Company. In May 1928, the Brunner-Winkle Aircraft opened their factory in the former Our Darling factory at 72-34 Charlotte Pl. (present-day 60th Lane) to manufacture the Bird bi-plane.

Reprinted from the July 28, 1983, Ridgewood Times.

* * *

If you have any remembrances or old photographs of “Our Neighborhood: The Way It Was” that you would like to share with our readers, please write to the Old Timer, c/o Ridgewood Times, 38-15 Bell Blvd., Bayside, NY 11361, or send an email to editorial@ridgewoodtimes.com. Any print photographs mailed to us will be carefully returned to you upon request.