The Interborough Express (IBX), the highly anticipated train line connecting Brooklyn and Queens, has finally entered into Phase One of its construction with the environmental review process, much to the dismay of many Maspeth and Middle Village residents.

The MTA hosted an open house informational session on Nov. 19 that featured a short presentation, an array of poster boards displaying a map of the line and about two dozen MTA employees scattered around the basement of Trinity Lutheran Church in Middle Village.

The affair was a who’s who of Queens movers and shakers, featuring community board members, Council Member Robert Holden, Council Member-elect Phil Wong, the Myrtle Avenue BID, civic and residents’ associations, representatives from local and federal offices and smattering of concerned citizens. After the brief presentation, an MTA representative announced there would be no Q&A, and the crowd erupted.

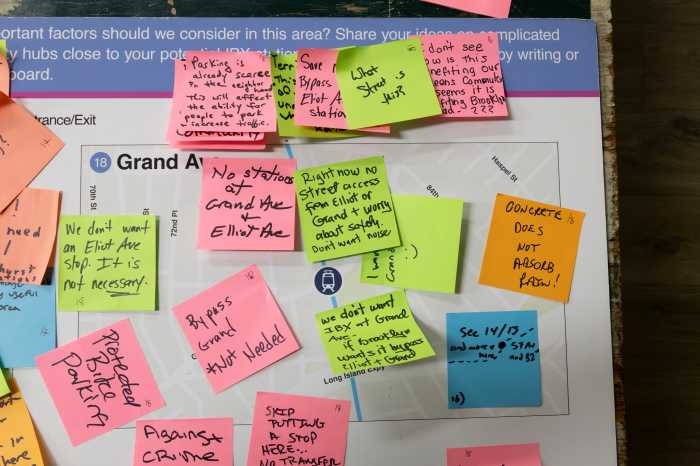

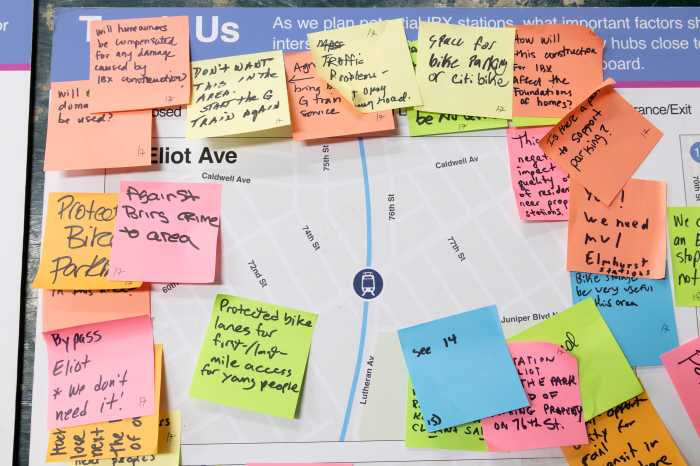

Volunteer representatives of the MTA were swarmed by attendees who ranged from inquisitive to confrontational. Fingers were pointed and complaints addressed, but the crowd’s largest grievance: not enough community input on the station’s location and the project as a whole, with many outright rejecting the idea of a stop for fears of eminent domain, rezoning and new development projects in the residential neighborhood.

Tale of Two Boroughs

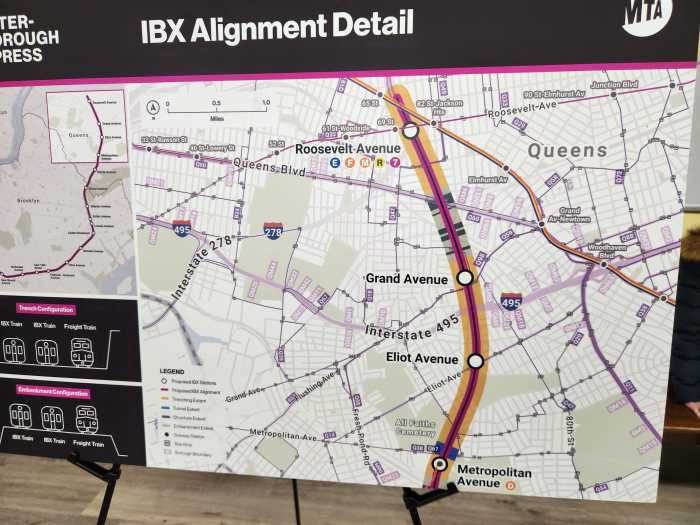

The $6 billion line will run from Roosevelt Avenue in Jackson Heights all the way to the Brooklyn Army Terminal in Sunset Park, and be New York’s first “light metro project” planted directly in the city’s largest public transit desert, providing 900,000 residents with a new transportation option. The path follows an existing freight line owned by CSX and the LIRR Bay Ridge Branch, and the MTA estimates it will cut travel times nearly in half, down to just 32 minutes by connecting with 17 other railroad lines.

“One of the main benefits of the project is how we connect within the subway system and save people time,” said Jordan Smith, a project manager for the IBX. “We want to hear from people how they would react to the project, how they would ride it, what their impressions are and we take all that feedback seriously.”

Residents present at the open house feared for the potential environmental impacts and public safety, such as noise pollution from the much higher volume of passing trains, the close proximity of trains to residential homes, and the potential influx of crime from increased foot traffic around the borough. For them, the risk to the community outweighs the benefits from the line.

“It’s the tale of two boroughs,” said Theoharis “Queens is residential, every single economic opportunity mentioned in the feasibility study is in Brooklyn. Build the opportunity zones, the jobs, the housing first. They’re saying… only 27,000 people travel from within Queens [compared to] 86,000 from within Brooklyn. It is a lot of misleading information.”

According to Klea Theoharis, who lives next to the operational freight line, she only sees about three to four trains pass by throughout the day, which she described move at a “snail’s pace.” Theoharis has lived in Middle Village for over 35 years, and recalled the shift in train speeds after one of the freighters derailed, and worries IBX trains travelling at higher speeds could put homes in danger.

If the more vocal community members present at the open house get their way, the IBX may not include all 19 of its stops, skipping two proposed stations on Eliot Avenue in Middle Village and Grand Avenue in Elmhurst, and instead connect the existing Metropolitan Avenue M train station to Roosevelt Avenue in Jackson Heights.

“It’ll turn our neighborhood into a high-rise,” said Holden. “Or at least much more overbuilt. They’re not upgrading the sewers… they’re not fixing the electrical grid, and we have some of the most blackouts in the city of New York. You’ve got to put the infrastructure in. It doesn’t work… somebody’s making a lot of money.”

Holden, a member of the Juniper Park Civics Association for 30 years, led a concerted effort in the early 2000s with other civics groups and found 75 volunteers in South Queens to create contextual zones in the neighborhoods surrounding the station, zoning only for 1-3 family homes. Holden said the IBX is a part of the City and Gov. Kathy Hochul’s plans to “throw that out,” and begin larger housing projects within Middle Village near the new line, and stated the station should be outright denied.

Residents nearby the proposed station fear houses will be seized via eminent domain to build the station and electrical sub-station required to power it, which would later snowball into rezoning efforts. Jack Nierenberg, vice president of the non-profit Passengers United, cited the 2nd Ave. and 125th St. subway station redesign in Harlem as just one example of the MTA’s potential use of eminent domain for the IBX.

“Eminent domain is standard for any kind of transportation planning project in which they’re forced to [use it],” Nierenberg said. “What they need to do is make sure that when they’re in the design phase and that they’re working to try to minimize the impact of it, they work with communities… because that’s where the community input is essential.”

The $2 billion Q train expansion is set to add three more stops from 96th to 125th Street, the largest tunneling contract the MTA has ever awarded. For the project, the MTA seized 20 properties via eminent domain, giving some families just 90 days to vacate their homes or businesses. For the Q train expansion, the owners and residents were given “just compensation” for the seizures, paying market value for the properties and relocation assistance by providing real estate agents, a list of available apartments and covering moving costs.

However, MTA representatives stated that the stations in Queens wouldn’t require the same use of eminent domain as in the cramped streets of Manhattan.

“IBX stations and passenger tracks are expected to be located within the rail corridor that exists today, which will significantly minimize the need to acquire property for future passenger operations,” said an MTA spokesperson. “If the MTA determines that a property needs to be acquired, we are committed to fully complying with all applicable laws governing the use of eminent domain.”

All Faiths Cemetery

As a “light metro project,” a medium point between light rail and the traditional New York subway, the MTA was able to shed even more time off of the IBX commute, marketing it as only taking 40 minutes to ride from end to end. However, a change to the original plan cut that time to the current 32 minutes. How? By expanding a tunnel underneath a cemetery, much to the chagrin of community members.

Encompassing 225 acres, All Faiths Cemetery is the final resting place for half a million people, including the parents and old brother of President Donald Trump. Within the massive graveyard, the small tunnel currently used by CSX as a freight train line, is simply too small to accommodate the extra tracks needed by the IBX. The MTA would expand it by digging a 520-foot tunnel underneath the cemetery, not disturbing any graves but potentially moving the Eternal Light Community Mausoleum.

“We don’t have the answers today, but we’re still in the design phase,” Smith said.

The MTA pitched the tunnel after community backlash from the IBX travelling above ground on Metropolitan Avenue and 69th Street for concerns on having the train included with daily traffic. While the official documentation includes several options, including the on-street version, a raised track and the tunnel, the map presented at the informational session displayed the line traveling via the proposed tunnel.

While the Superintendent of All Faiths Cemetery, Brian Chavanne, told amNewYork in 2024 that moving the mausoleum would be feasible and preferable to the train running on the street, the expansion could increase the project’s $3 billion price tag.

“The MTA has a team of designers and engineers minimizing disturbances during construction. We’re committed to working with the cemetery and stakeholders throughout the process,” said an MTA spokesperson.

Public transit desert

Middle Village is far less densely populated than even its bordering neighborhood, Ridgewood, with only half the population despite the similar size. According to the New York census, 1 in 4 households within a half-mile of the Eliot Ave. stations do not have access to a car, and 61% use public transit to get to work. As a result, around half of those who work in both Brooklyn and Manhattan have a commute over an hour long.

“Public transit in neighborhoods is good for everyone. Better transit puts money in your pocket — shorter commutes means more economic mobility and relying on a car for every trip costs nearly five figures each year. Better transit means cleaner air, and less congestion for those who have to drive,” said Ben Furnas, the executive director of Transportation Alternatives (TransAlt), a non-profit organization that advocates for biking, walking, and public transit.

Mayor-elect Zohran Mamdani appointed Furnas, who the New York Post described as a “car-hating activist,” to the transportation, climate and infrastructure department of his transition team. However, Furnas only spoke on the IBX as the leader of TransAlt, and not as a member of Mamdani’s transition team.

“Transit access doesn’t hurt communities, it helps them thrive; there are neighborhoods in every corner of New York City that look much like Middle Village but residents enjoy much quicker and more reliable commutes,” Furnas said. “Once the IBX is built and running, and the fear-mongering subsides, residents won’t know how they lived without it.”

Nierenberg understands the benefits the IBX can provide to the Queens community, just as long as the MTA takes the correct approach. Nierenberg stated the MTA and state government have “consistently failed in the past” to properly utilize community input, including on the IBX, by not holding even more community outreach events like the open house.

“Properly consider the impacts of this on people, and also show a genuine interest to prevent… these developers from engaging in predatory development, which would exacerbate and accelerate gentrification and displacement,” Nierenberg said. “Promise the people in the communities that they’re actually going to benefit from this, and one way to really make sure that they do, is to listen to them and accommodate them.”