By Matthew Monks

An investigator from Riverwalk, a New York City-based environmental advocate, along with City Councilmen Eric Gioia (D-Sunnyside) and David Yassky (D-Brooklyn) filled jars with oil and diesel fuel collected from murky pools along the heavily polluted waterway.

The samples are ammunition for a lawsuit they are prepping against six companies, including ExxonMobil Corp. and BP Amoco Corp., charging the defendants have failed to properly mop up a 17-million-gallon oil spill beneath Greenpoint, Brooklyn,

Touring the polluted creek that divides Queens and Brooklyn Friday only strengthened the plaintiffs' resolve to make someone pay for what they say is one of the world's most severe environmental catastrophes: a half-century-old oil spill that exceeds the 1989 Exxon Valdez spill by at least 6 million gallons.

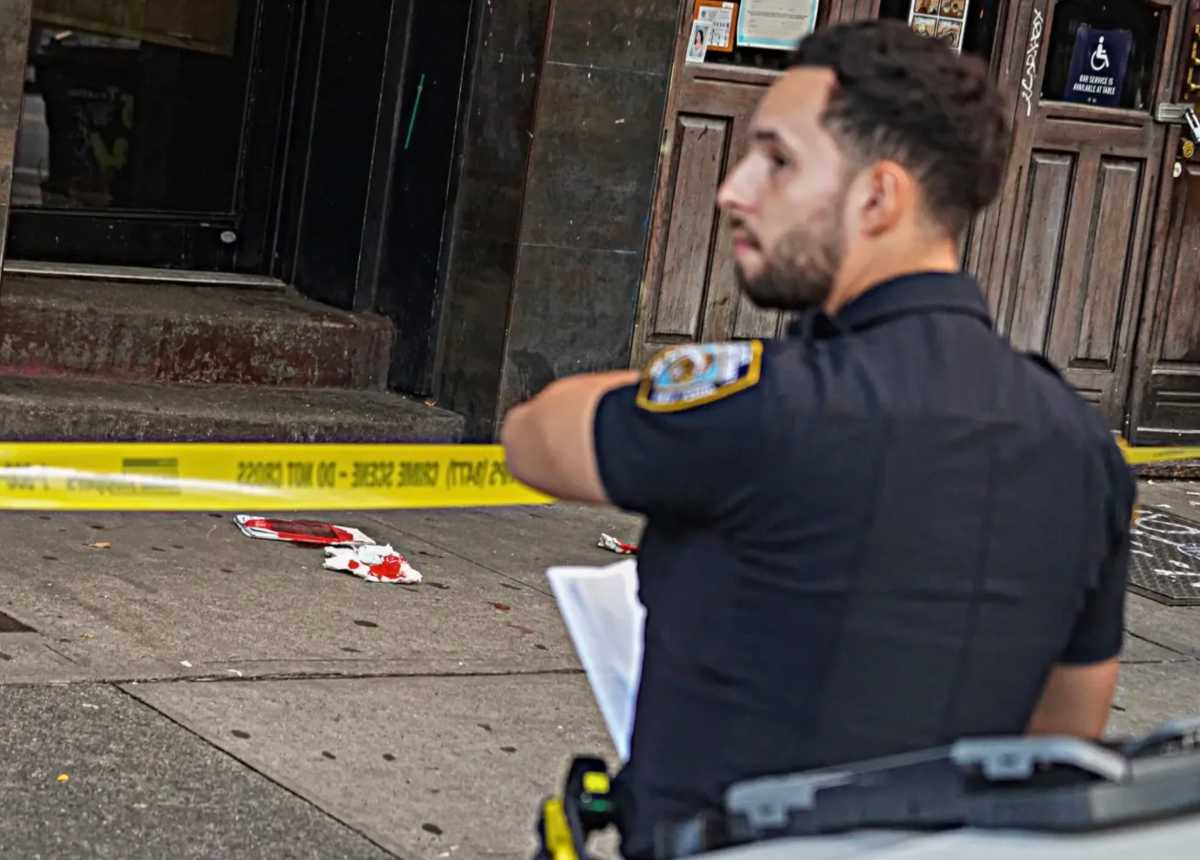

“It's pretty devastating to see this,” said Gioia, pointing at a grimy, coffee-colored puddle within a containment boom behind Peerless Properties Corp. in Brooklyn. “This is the smoking gun, we're watching a crime in progress.”

“The damage to the environment and people that live here is sickening,” added Yassky, who noted the oil rests near the water table under 100 homes on 55 acres between the Greenpoint Avenue and Kosciusko bridges in Brooklyn. “This lawsuit is designed to make the people who did this clean up their mess … We're not talking two teaspoons dropped into the ocean.”

Gioia said property along the Newtown Creek, with its spectacular views of the Manhattan skyline, has the potential to be one of finest spots in the five boroughs. With the proposed Olympic Village at the mouth of the creek in Queens, the area could be the future of New York City, he said.

Instead, he said, the spread is dragged down by decades of environmental abuse.

“This should really be the Brooklyn/Queens Gold Coast,” Gioia said. “The waterfront should really be accessible.”

There is just one public dock along the 3.5-mile-long creek. But even if people could reach the water, he said, why would they want to?

Riverkeeper filed more than 15 lawsuits last year against entities it said were illegally polluting the waters, investigator Basil Seggos said. Just last week, he said the group began investigating the source of an oily substance seen floating near the end of Lombardy Street in Brooklyn.

As the councilmen and Seggos navigated the creek Friday, they passed dozens of signs of abuse. Floating garbage and countless rainbow-colored oil sheens drifted past their 36-foot lobster boat.

As they neared the Peerless site, where Seggos said oil from the spill continually seeps into the creek, the air reeked with the stench of gasoline.

“It's thick black all through here,” Seggos said, pointing at a syrupy black pit within a containment boom. “I wouldn't smoke near it.”

The leak behind Peerless allegedly migrated over five decades from property about a quarter mile to the north that is currently home to an ExxonMobil refinery, Seggos said. The spill originated from a series of leaks and a sewer explosion in the '40s and '50s, when the property was owned by the Standard Oil Company of New York, Exxon's predecessor, Seggos said.

The state Department of Environmental Protection in 1990 ordered Exxon to begin cleaning up the spills, but Riverwalk and the councilmen contend the order was too lax, setting no deadline and delivering no penalties. As a result, they say, only 3 million gallons of oil has been removed from the creek and surrounding area.

ExxonMobil officials did not return phone calls for comment.

Seggos said the lawsuit, which also names Roux Associates and Peerless, is meant to force the companies to speed up the recovery by digging more wells and prompt them to develop a plan to treat the contaminated soil once the free oil is collected.

Riverwalk filed its intent to sue on Jan. 20 under the federal Clean Water Act and federal Resource Conservation and Recovery Act, which require a 60-day and 90-day notice period, respectively. Yassky and Gioia joined the suit on March 8.

The Clean Water Act says it is illegal to discharge pollutants into waterways without a permit, and the Resource Conservation and recovery Act prohibits the dumping of hazardous material that may create endangerment.

Each day that oil seeps from the steel bulkhead behind Peerless Imports, the defendants are breaking the two laws, Seggos said. Riverwalk continually cruises the creek in its lobster boat to collect samples to use against the oil companies in court when the group files its lawsuit in late April.

Riverwalk is scheduled to meet with ExxonMobil and BP Amoco sometime in April to discuss the charges. Seggos would not disclose the date.

Reach reporter Matthew Monks by e-mail at news@timesledger.com or call 718-229-0300, Ext. 156.