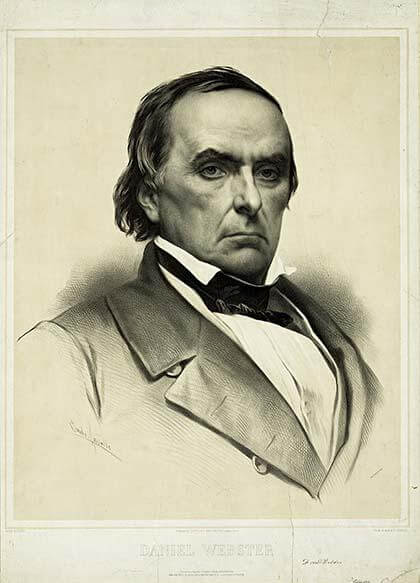

By Joan Brown Wettingfeld

In what is known as the Webster-Hayes debate, Daniel Webster argued for “the supremacy of the federal government.” With all of his notable abilities and accomplishments, Webster unfortunately did not achieve his hope of succeeding one day to the presidency. He was, however, in negotiations over the Webster-Ashburton Treaty in 1843 to achieve what turned out to be his greatest diplomatic success. This treaty dealt with our country’s northeast boundary.

To do justice to Webster’s role in our country’s history would, at best, be a monumental task. His role in politics and public service ranged from 1805-22. After being educated at Exeter and Dartmouth colleges, he studied law, which he briefly taught. He was then admitted to the New Hampshire bar in 1805. His law practice was his entrée to political activities and soon he represented his home state in Congress. But he made it evident that he opposed the War of 1812.

Webster made the move to Boston and it was evident he had earned the position as the nation’s leading attorney. This, in turn, was to lead him to the role as our nation’s greatest orator of his era. Notable at that time was his delivery of his speech on the bicentennial of the founding of Plymouth, and the response was the same when he spoke at the dedication of the Bunker Hill monument in 1825.

After his election to Congress in 1822, he was to serve in the U.S. Senate for a good number of years and joined the Senate from 1827 to the 1840s. He would then desert his early free trade interests for the “tariff” as a national interest.

In his 40 years of service and as a leader of the Whig Party, he also served as a leader for the modernization and individual interests of New England.

As he would say, “Liberty and union, now and forever, one and inseparable.”

One of the most important exchanges in Senate history took place in 1830, when Webster was to argue for the supremacy of the federal government. At that time Webster, and President Andrew Jackson were united in their opposition to nullification despite a long history of disagreement on almost every other issue. Webster’s greatest diplomatic achievement occurred in 1843, when as secretary of state under Presidents William Henry Harrison and John Tyler, Webster was to negotiate the Webster-Ashburton Treaty.

Later, he served once again in Congress in the Senate, where he worked diligently on the Compromise of 1850. Opposed as he was on the issue of slavery, he accommodated the Southerners because of his belief in the preservation of the Union as the more important cause.

From 1850 until his death, Webster was to hold the position of secretary of state under President Millard Fillmore. Webster died Oct. 24, 1852, in his home.

Joan Brown Wettingfeld is an historian and freelance writer.