Francis Lewis, a science teacher at the High School of Contemporary Arts in the Bronx, is displeased with incoming students’ lack of basic educational skills.

“I see the students that come in and the deficiencies they have,” said Lewis. “Not everyone can read.”

Fed up with sub-standard achivement, Lewis, along with partner and fellow teacher Dennie Wilson, submitted a bid to open a charter school. Their potential institution, the Community Charter School for Success, is one of seven charter schools vying for spots in Queens that have advanced to the rigorous second and final round of applications.

“Charter schools are important because they allow flexibility,” said Lewis. “You’re not dealing with bureaucracy but with innovation. It gives you autonomy as well. You can focus more on results rather than bureaucracy.”

The Community Charter School for Success hopes to promote problem solving and critical thinking, focusing on mathematics and literature — subjects Lewis refers to as “building blocks of success.”

The educators applied with the Department of Education (DOE) to host their school inside Far Rockaway’s Alternative School 222 in School District 27, an area Wilson says does not currently have a charter middle school. Lewis says the addition of a charter school could quell crowding among the borough’s packed facilities, reducing class sizes from 35 students down to 20.

The new slate of potential schools also includes a Flushing-based Chinese language and culture institution, called the Whole Elephant Charter School. The curriculum will include martial arts training, traditional painting techniques and East Asian language courses.

While charter schools have a controversial history, Wilson feels adequate community outreach has pacified some negative attitudes.

“Some people are for charter schools, some people are against them,” said Wilson. “We’ve treaded the water cautiously, reaching out to people and explaining the need for a charter school.”

Lewis claims ill feelings towards charter schools spawn from co-location tensions voiced by parents, fearful charter students could displace public school kids.

“For the most part, some schools are not friendly to new tenants,” said Lewis. “We’re very much aware of that.”

There are 159 charter schools throughout New York City: 61 in Brooklyn, 44 in the Bronx, 40 in Manhattan, 11 in Queens and three in Staten Island.

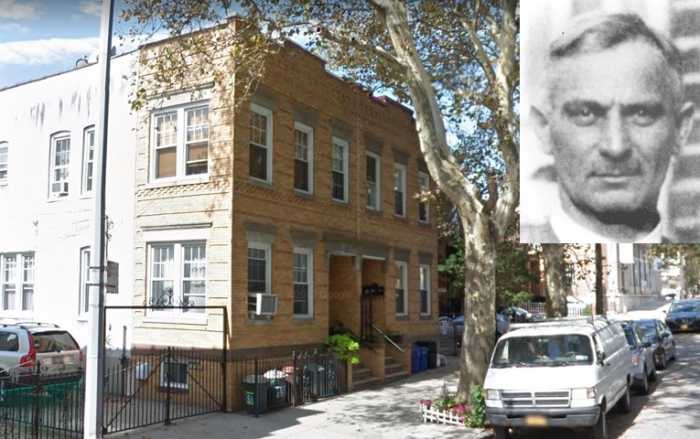

The Central Queens Academy Charter School is the newest addition to the borough’s roster. The middle school will open this fall in a private, undisclosed location in School District 24.

According to Petra Tuomi, a spokesperson from the New York City Charter School Center, institutions must form five-year-long contracts, as they operate independently from the Department of Education (DOE). Tuomi said this freedom allows schools to operate by their own standards, administering lengthier academic years, designing custom curriculums and selecting their own teachers and staff.

Class sizes are generally smaller for the 56,600 students who are enrolled in charter schools across the city. Schools receive the same amount of funding as district schools — $13,527 per pupil from the DOE — as well as grants from private donors.

While Queens is the borough with the highest rate of overcrowding in schools, Tuomi assured the addition of charter schools does not displace public school students.

“It boils down to the availability of public space,” said Tuomi. “Every school deserves room and equal access to public space. That has been a reason why it’s tougher to start charter schools in Queens — limited access to public space.”