Citylights residents rallying at Gantry Plaza State Park on Jan. 3 for tax relief. (via Comptroller Stringer)

Jan. 4, 2019 By Christian Murray

To some, buying a Citylights co-op in 1997 could be viewed like winning the lottery.

Units in the 42-story building fetched as little as $10,000 in 1997 when the building first opened.

Today, those same units sell for about $600,000–or can be rented for $3,000 to $4,000 per month.

But residents in the 522-unit coop at 4-78 48th Ave. are not rejoicing. Instead they are out protesting a property tax hike, as the building’s 20-year tax abatement has finally run its course. Their maintenance bills are being increased by 9 percent each year for the next five years to cover the large tab.

The tax hike, which went into effect in July, means that unit owners will see about a 50 percent jump in their monthly maintenance fees over 5 years. One unit owner said her maintenance is projected to go from $2,600 a month to $3,900 per month in 2022.

The co-op owners at the Hunters Point building have been holding rallies for the past several months—joined by local officials such as State Sen. Mike Gianaris and Council Member Jimmy Van Bramer—fighting back against the hikes and arguing that the changes will force many of them to leave.

On Thursday, Citylights residents rallied once more at Gantry Plaza State Park, and were this time joined by City Comptroller Scott Stringer, who called for the city and state to grant these co-op owners relief.

The protest came in light of the recent deal to bring Amazon to Long Island City, with Stringer arguing that if the city and state could provide the tech giant with $3 billion in subsidies to build out its campus, that they should help Citylights co-op owners, too.

“It’s time that we show the people who built this city that we value them just as much as a multinational corporation and give them the relief they deserve,” Stringer said.

The rally came one day after Stringer wrote to Mayor Bill de Blasio urging him to work with the state and the co-op board and come up with a solution.

“Particularly in the context of the literally billions of dollars in inducements the City and State are providing to bring Amazon to Long Island City, the cost of extending tax relief to these Long Island City homeowners would be trivial,” he wrote.

Citylights from Gantry Plaza State Park (Photo: WiredNY)

The tax hike for Citylights residents stems from two factors—an expiring state tax abatement, and a city assessment of the building that doubled its value in recent years.

The building’s 20-year tax abatement provided by the state—similar to a 421 a tax-exemption program that many condos benefit from– is being phased out over the course of the next five years.

Under the abatement, the co-op built on state-owned land didn’t have to pay property tax until July 2018, when the phaseout began.

But the tax is now being phased in at 20 percent per year until 100 percent of the assessed taxes are payable starting July 1, 2023.

For fiscal year 2019, the building is subject to $800,000 in property taxes, which will go up to $5.8 million over five years.

The total maintenance costs of the building, as a result, are projected to go from $10 million to $16 million in fiscal year 2023 with the hike.

The tax, meanwhile, is based on the building’s assessed value that went from $51.7 million in 2016 to $101 million in 2018 after a review from the city Department of Finance.

The co-op board claims that the valuation is inflated and is appealing the agency’s decision.

The original co-op purchasers also argue that the building was pitched by the state as “affordable” in its bid to lure middle income people to the area, and that they took a chance on Hunters Point as “pioneers” when the neighborhood was desolate.

Indeed, studios could be bought for as low as $10,000 at the time, with three-bedroom units fetching around $65,000.

But the trade off in offering units at low prices was that the owners would collectively be responsible for an $86 million mortgage that covered a large chunk of the development costs. That mortgage kept purchase prices low, but inflated maintenance payments in order to service the debt.

The co-op owners still owe about $86 million. Today, the building pays $4.5 million each year to service the loan.

Residents say they don’t have the means to cover the loan, the taxes and other maintenance costs.

Despite the rallies and the co-op building’s financials, people continue to buy units and pay big prices.

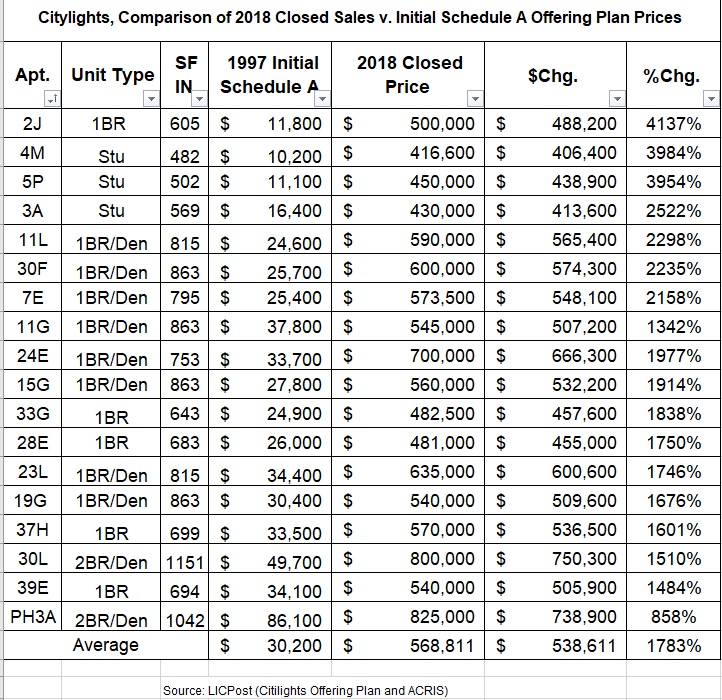

For instance, a one-bedroom unit with a den sold for $600,000 in 2018, a significant jump from the unit’s original offering price of $25,700 in 1997.

Meanwhile a 2-bedroom unit that was originally offered in 1997 for $49,700 sold for $800,000 last year—a profit of $750,000.

Citylights offers panoramic views over the East River and Gantry Plaza State Park (11th Floor view)

In 2018, the average price paid for a co-op in Citylights was $569,000, according to a Citylights market report released by Patrick W. Smith of Stribling & Associates this week.

The majority of the early coop owners, meanwhile, have sold their units since the building opened, with about 300 sales transactions taking place in the last decade.

Some have made large profits over the years. For instance, Eric Gioia, the city council member prior to Jimmy Van Bramer, bought a unit in Citylights in 2004 for $195,000 and sold it for $372,000 in 2007.

About 40 percent of the current owners are the same people who bought units back in the late 1990s, Shelley Cohen, the building’s treasurer said in July 2018.

Some apartments listed by unit holders on StreetEasy also provide insight into pricing. One bedrooms are listed at $2,900 and 2 bedrooms at $4,500.

However, residents continue to cry foul.

“The City and the State are extending handouts to big companies, like Amazon, while my middle-class neighbors and I suffer,” Cohen said in a statement after the rally.

The state said over the summer that it is willing to negotiate the terms of an abatement and possibly extend it to 35 years, as some residents prefer, but that it needs the city to step in, too.

The city, however, said at the time that it is aware of the issue, and that the tax commission is reviewing the building’s appeal for the property’s tax assessment.

Stringer said Citylights residents took a chance in coming to the area and are the backbone of the neighborhood.

“Yes, change comes and skylines change, but the people who build our communities—our pioneers—they must stay,” he said. “They must be celebrated.”