Eighteen months after a five-alarm fire gutted a Queens apartment building, dozens of displaced tenants remain locked out of their homes — and now, state lawmakers are proposing legislation to hold landlords accountable for prolonged repair delays across New York City.

The fire ignited just before noon on Dec. 20, 2023, at 43-09 47th Ave. in Sunnyside, as residents prepared for the holiday season. Investigators determined the blaze was caused by a contractor hired by building owner A&E Real Estate. The contractor was illegally using a blowtorch during construction work.

What unfolded in Sunnyside has become a symbol of a broader crisis. Across the five boroughs, tenants displaced by fires often wait months — or even years — to return home, as landlords delay essential repairs and face few consequences. The Sunnyside case has galvanized lawmakers to push for stricter enforcement and firm deadlines to accelerate recovery and protect tenants left in housing limbo.

The December 2023 inferno displaced approximately 250 residents, many of whom had lived in rent-stabilized units for years. More than half of the apartments in the six-story, 107-unit building were rent-stabilized or rent-controlled, including the home of Lauren Koenig, who had lived there for 13 years and paid $2,650 in monthly rent for her stabilized unit.

For Koenig, reentering the housing market after more than a decade in a regulated apartment has been financially and emotionally overwhelming.

“It was a perfect storm,” she said. “You’ve got the holidays, housing crisis, inflation.”

In the aftermath of the fire, A&E Real Estate offered displaced tenants six-month temporary relocation license agreements, allowing them to rent units in other A&E-owned buildings at the same rate they had paid in Sunnyside. Under mounting pressure from elected officials and community members, the company later extended the agreements twice — each time for an additional six months.

But tenant Lauren Koenig said most residents turned down the offers, noting that the available apartments were located far from their Sunnyside neighborhood — in the Bronx or deep into Queens — effectively uprooting them from the community they had long called home.

“Only about 25 people took the deal, because it’s a raw deal,” Koenig said. “I didn’t take it.”

Koenig said tenants had repeatedly asked A&E to offer alternate housing in its other Sunnyside properties, but the company was not responsive. As a result, she spent nearly a year without stable housing, relying on the generosity of friends and moving between apartments as she searched for something suitable in the area.

“I don’t have kids — I only have to take care of myself,” she said. “I can’t imagine the pain of trying to do this while caring for an elderly parent, or with a newborn, young children, or pets. I cannot imagine what others went through.”

Koenig eventually secured an apartment nearby, but it came at a steep cost: $3,100 per month — $500 more than her previous rent-stabilized unit — amounting to a $6,000 annual increase.

In response, an A&E spokesperson said the company had only a limited number of vacant units in Sunnyside and insisted it “did its best” to keep displaced residents in the neighborhood. While acknowledging the hardship tenants faced, the spokesperson called the situation “imperfect” and maintained that the company’s options were limited.

Melissa Orlando, a market-rate tenant who was displaced by the fire, said she immediately found another apartment in the area because she had a young son and didn’t want to “bounce around” from place to place. Furthermore, she was going from one market rate unit to another, so the price difference wasn’t vast. However, many tenants with rent stabilized and rent controlled units could not afford comparable apartments at the new price.

“Fortunately, I had the means to go and find a new place to live, but the rent-stabilized and rent-controlled tenants in that building are here, there and everywhere, scattered, all over the city,” Orlando said. “A lot of them have been in that building for very long time… and if you’re in something that was stabilized or rent-controlled and now to have to go out into the market, that’s a serious shock.”

On the day of the fire, Orlando heard sirens but smelled no smoke. She left her apartment only after checking the Citizen app, grabbing whatever essentials she could. At the time, she assumed she would be able to return home later that evening.

In the shock of watching the fire rip through the building, Orlando admitted thinking that she might be able to re-enter her apartment that evening.

In the days immediately following the fire, Orlando said A&E appeared responsive, setting up a temporary office across the street, distributing holiday gifts and meals to impacted families. But that initial cooperation quickly faded. After Christmas, Orlando said, A&E’s tone shifted — and interactions with tenants became increasingly tense.

“Every step of the way it’s been a fight with them,” she said.

Orlando also said the alternative accommodation offered by A&E was in “far-flung places” where she didn’t feel safe walking at night.

Nearly 18 months later, no repair work has begun on the building, despite repeated calls from tenants, elected officials, and city agencies. The city’s Department of Housing Preservation and Development is now suing A&E to compel them to begin restoration.

In response to the prolonged displacement, State Senator Michael Gianaris — who represents Western Queens — introduced legislation aimed at holding negligent landlords accountable in the wake of fires and other emergencies.

The bill, inspired by the Sunnyside fire, would require property owners to provide suitable housing to any tenant forced to vacate due to a fire. If the owner is found negligent or responsible for the fire, HPD would be authorized to find alternate housing for tenants — with the landlord responsible for covering the cost.

The financial obligation would remain in place until HPD determines the tenant’s original unit is fully repaired and habitable.

While the legislation wouldn’t force landlords to carry out repairs, Gianaris said it would create a strong financial incentive to do so quickly.

“It would incentivize the rehabilitation of the building so that people can go to their actual homes much faster, because the longer that a landlord is expected to pay for suitable accommodations, the more the incentive is for them to actually fix the building itself so people can get back in their homes,” Gianaris said June 16.

Gianaris’ legislation was passed by the State Senate in the closing days of the session last week, but companion legislation introduced by Assembly Member Claire Valdez — who also represents western Queens — died on the floor because there were concerns about the technical language of the bill and how the bill would be implemented.

Gianaris has signaled his intent to reintroduce the legislation when the Senate reconvenes next year but said it is “disappointing” that the bill will not be passed this time around.

“This is of tremendous significance,” Gianaris said, adding that tenants who have been displaced from Sunnyside as a result of the fire have been disconnected from vital services, ranging from long-term doctors to schools.

Koenig said she was “heartbroken” to hear that the legislation will not pass in this session. Orlando, meanwhile, said the legislation would have been “extremely helpful” for cases of clear-cut negligence.

“I think the legislation would be a godsend for people,” Orlando said.

Displaced Sunnyside tenants have alleged that A&E is dragging its heels over repairs as a tactic to remove units from rent-stabilization and make them market rate. Elected officials, including Queens Council Member Shekar Krishnan and Brooklyn Council Member Alexa Avilés, have alleged that certain landlords have delayed repairs for that very reason.

“These are all pretty long-established tactics that landlords have used to get units out of rent stabilization and also to displace long standing tenants,” Avilés said.

HPD Press Secretary Matt Rauschenbach said the agency’s “top priority” is to ensure that all New Yorkers remain safe in their homes, noting that HPD has issued a vacate order for all 107 units in the Sunnyside building.

“HPD will continue to work and take steps to hold the owners accountable to making the repairs that are required of them,” Rauschenbach said.

Again, A&E pushed back strongly against the allegations. A company spokesperson said it is completely untrue that buildings are left in a state of bad repair to take rent-stabilized units off the market. The spokesperson said New York City law mandates that a unit’s rent-stabilized status must be maintained now matter how long repairs take.

They added that the building is “hemorrhaging money” in its current state as A&E cannot collect any rent. They further argued that A&E made all necessary repairs to prevent further damage immediately after the fire but said further repairs have been hamstrung by the building’s insurance company, who allegedly insisted on carrying out the repairs themselves rather than providing A&E with the means to do so.

“Every day this building sits empty is a loss for us, and a hardship to the families that called it home,” an A&E spokesperson said. “Since the insurance company took complete control of the rebuilding process, it has slowed to a crawl. We are applying every pressure we can to get this process moving.”

Gianaris called A&E’s explanation “absurd,” criticizing the company for citing insurance complications as an excuse for failing to carry out repairs.

The Sunnyside blaze is one of many fires in recent years that have displaced thousands of residents across New York City. In countless cases, tenants have faced prolonged and agonizing waits for suitable housing, often left without clear timelines or support as they navigate uncertain futures.

According to HPD data, the median length of stay in emergency housing shelters provided after a fire in New York City is 260 days, with that figure reaching almost 600 days among single men.

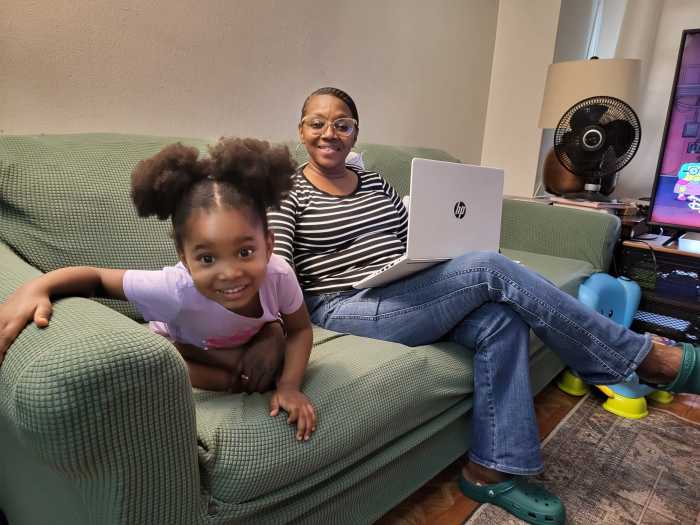

Yolanda Richardson, 58, had been living in her rent-stabilized apartment in the Bronx for 25 years when a five-alarm blaze struck the six-story building on Jan. 10.

When Richardson and her 250 neighbors were forced to flee their 2910 Wallace Ave. building in the middle of the night, she said she lost everything — including the opportunity to pay just $1,348 per month for a two-bedroom apartment.

The fire broke out on the top floor where Richardson lived, and the entire building was placed under a vacate order that still remains in effect. After an investigation, the FDNY determined the fire was caused by faulty electrical wiring under the watch of notorious landlord Ved Parkash, who has racked up thousands of housing code violations across his portfolio and topped the city’s Worst Landlords List in 2015.

The Wallace Ave. building was the third Parkash building to catch fire in less than two years — each time due to faulty electrical wiring, the FDNY found. In June 2023 alone, fires broke out at two of his other Bronx properties, 1420 Noble Ave. and at 735-745 East 242nd Street, where two people died.

Fortunately, no one was killed in the Wallace Avenue fire. But Richardson and her neighbors, a close-knit group of mainly working families, are now scattered all over the city and even the country.

As other examples have shown, it will likely take years to rebuild. A spokesperson for Parkash Management did not provide a timeline but said in a statement that repairs “are progressing in accordance with all city permits and regulations. We will continue to update tenants as new information becomes available.”

In the meantime, Richardson went from comfortably living in the mid-central Bronx to couch-surfing among friends and relatives in other states, finally landing in her mother’s living room in “deep Brooklyn.”

As much as she loves her mother, the situation is uncomfortable and difficult for someone accustomed to independent living, said Richardson. “I’m gonna be 59, and I’m on my mother’s sofa!”

Richardson and her mother aren’t the only ones impacted. Her three nieces, ranging from preschool to adult age, also live in the household, and Richardson feels she’s constantly disrupting — and being disrupted by — their daily routines.

“I feel like I’m impeding on all of it,” she said. “I’m in tears constantly.”

In Richardson’s view, the residents displaced from the Sunnyside, Queens fire were fortunate to be offered temporary stays at other apartments within the owner’s portfolio at the same rate. Allerton tenants have not received such an offer, she said.

A few residents did move into other Parkash units, but they had to pay the current asking rate — not their rent-stabilized rate — and sign standard leases, which may make them unable to move back to Allerton as soon as the building is repaired, according to Richardson. Very few residents seem to have taken this option, she said.

Another unpopular option among the Wallace tenants was taking on debt via low-interest federal loans made available to them, as Governor Kathy Hochul announced in March. At the time, Richardson called the loans “a slap in the face,” and she and her neighbors have since rallied multiple times, including at City Hall in May, for more meaningful housing assistance from the city.

The displaced residents have said for months that the city or Parkash should cover their housing costs while the building is being repaired. Even an arrangement where the tenants paid their previous rate while a city voucher or Parkash covered the difference would be fine for most, Richardson said. “I know I’m not gonna find that [previous] rent anywhere, so I’m not unrealistic about that.”

HPD is taking her landlord to court for repairs. A HPD spokesperson said the agency is actively pursuing “comprehensive” litigation for 124 open violations at the building, noting that the agency has also concluded the clean-up of asbestos containing material at the building. Emergency work ordered by the Department of Buildings is currently underway.

“We’ll continue to push forward and hold this owner, and all owners, accountable until all necessary repairs are made,” a HPD spokesperson said.

Meanwhile, the City Council is also taking steps to assist tenants displaced by fire or other emergencies, passing a package of bills in 2024 that serve to benefit impacted residents.

One piece of legislation, introduced by Council Member Avilés, requires HPD to provide tenants displaced by a blaze with handouts detailing their occupancy rights. HPD must also inform impacted tenants with of the process for rescinding a vacate order and what their landlord is required to do under the law.

A second piece of legislation, introduced by Bronx Council Member Pierina Ana Sanchez, requires the city to notify council members when a fire takes place in their district to help ensure that impacted families get the help they need.

Council Member Krishnan has also introduced legislation that, if passed, would require HPD to relocate vacated tenants to homeless shelters in their current community districts, rather than placing them in other areas or boroughs.

A separate piece of legislation introduced by Krishnan would require HPD to appoint a nonprofit administrator to oversee building repairs and collect rent if a landlord does not enact repairs within a given timeframe. Neither bill has been passed by the Council.

Aviles, speaking to amNewYork on June 18, said her legislation aims to address a critical information gap, especially for tenants who don’t speak English as a first language. She said “traumatized” tenants often rejected offers for emergency accommodation when they were offered it directly after a fire, with that initial rejection permanently preventing them from obtaining emergency shelter accommodation.

“When buildings receive vacate orders, folks should understand what their rights are,” Avilés said.

Displaced tenants are often unaware of their rights, Avilés said, noting that tenants can retain a connection to vacated rent-stabilized units by paying as little as $1 per year. Many tenants, however, are unaware of this and lose their connection to the rent-stabilized unit, she added.

“Once that connection gets severed, you can’t get it (a rent-stabilized unit) back,” Avilés said.

Avilés also believes the city can do more to help prevent fires in the first place, calling for HPD to demonstrate more proactive enforcement and ensure that landlords pay hefty fines for code violations.

She said Krishnan’s legislation requiring the city to take legal action against landlords who delay repairs would also help provide accountability and help displaced tenants return to their homes.

“I think landlords should be held accountable,” Avilés said. “If we are seeing landlords either delay repairs keep tenants out for long periods of time, we should be able to hold them accountable for that.”