Around the streets of Jackson Heights, Elmhurst and Corona in Queens, the large community of Latino residents that call these neighborhoods home is evident. It is also visible that street vendors are a staple of the neighborhood, and the smell of various traditional dishes is a common sense appeal among the streets.

As the food gives residents a good taste of their native countries, street vendors serve a bigger purpose than making a living. Many of the vendors take a risk, as they may work without a license. However, when their livelihoods become dependent on providing this service, it is a sacrifice that they are willing to take.

In May, a New York City Council hearing was granted regarding the Street Vendor Reform Package. The proposed package received a breakthrough on Sept. 10, as Council Member Shekar Krishnan, who represents Jackson Heights, Elmhurst, East Elmhurst and Woodside in Queens, passed Intro 47-B.

The bill was enacted after the City Council voted to override Mayor Eric Adams’ veto of Intro 47-B. Under the act, street vendors will no longer receive criminal misdemeanor charges as a penalty for street vending violations.

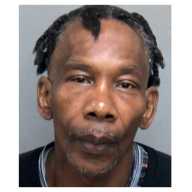

“It’s not the same when you hear it directly from the person who is living through it,” said Cleotilde Juárez, a small business owner in Queens and Leadership Board member with the Street Vendor Project. “Many of us are mothers, and even single mothers.”

Juárez worked as a street vendor for about five years, before she opened up her own restaurant in April. Her restaurant, Chalupas Poblanas El Tlecuile, in Corona, was something she had envisioned as a 14-year-old.

Still a teenager, she recalled a woman who sold chalupas at her village, San Matías Cocoyotla, in Cholula, Puebla, Mexico. Juárez received the privilege to work with the woman’s daughter-in-law, where she observed the woman at work firsthand. She recalls “falling in love” with her dishes, and at 19 years old, Juárez began selling chalupas herself.

She has served the dish for over 25 years, but it wasn’t until 2020 that she introduced her chalupas to the Queens community. As the COVID-19 pandemic left her unemployed, and her kids were ineligible for government aid, Juarez sold chalupas on Junction Boulevard in Queens.

During her time as a street vendor, Juárez went through similar struggles as many others who sell food to make a living. Over the years, she had received many fines. But she stated the fines weren’t all that vendors had to look out for. Encounters with authorities were “very terrible,” which often led to arrests or vendors having their food thrown away.

“You couldn’t do anything against the authorities,” said Juárez. “You were left with frustration. Feeling afraid. Feeling sorry. Left in tears. They take away your livelihood. The livelihood that puts food on your table, and pays your rent.”

Fines went as high as $1,000, and Juárez says the degree of stress was “enormous.” She recalled seeing fellow food vendors who suffered from facial paralysis. There are also vendors who are diabetic, and their glucose levels were affected due to distress. As many are elderly and unfit to work, they prefer to sell food to pay for their expenses.

“They don’t realize how important we are to this community,” said Juárez. “If you received a fine, you went to a criminal court. We aren’t assassins or rapists. We are hard-working women. It’s very disrespectful that they viewed us in that manner and treated us horrendously.”

Juárez became a street vendor out of necessity, but says has it has since become a more “caring connection” to her fellow country people. She has served families who haven’t returned to Mexico in over “20 to 35 years.” They’ve expressed their appreciation for her dishes, which made them feel closer to home. As many of the families have children who are first-generation Americans, they also become more familiar with the culture of their roots.

As the community has a large immigrant and working-class demographic, Juárez emphasized that street vendors also play an important role in providing economical dishes.

“If I were to die tomorrow, I would die happy,” said Juárez. “Because I did something for the people of my country. Who haven’t been able to return home, and enjoy our food.”

After criminal misdemeanor charges were removed as a penalty for street vending violations, the Leadership Board member of SVP maintains hope that the remaining bills under the reform can be passed. The reform can bring many benefits to the city’s economy, in addition to the street vendors’ livelihoods.

Juárez pointed out that street vendors would pay for the granted licenses, and any required vendor courses. There would also be a significant increase in tax revenue, as 75% of street vendors currently operate without a license.

“There would be nothing more dignifying than to work in peace and tranquility,” said Juárez. “It’ll be a sense of peace and tranquility that words can’t describe, priceless. After many years of being persecuted. And so many years of being threatened.”