By Corey Bearak

I always paid attention to events in the Middle East and efforts to bring peace to the region. From my Jewish heritage and its focus on the Promised Land to an early fascination with T.E. Lawrence after watching the epic film “Lawrence of Arabia” — still my favorite — I followed the wars, the efforts at peace and the terrorism that found its way here when hijacked jetliners toppled the Twin Towers.

Queens enjoys a large Jewish community manifested in Kosher shopping, synagogues, Jewish community councils and programs at our colleges. Residents of other Middle Eastern lands arrived more recently in Queens and contribute to its diversity. Israelis are a growing segment of the Queens Jewish community. Our focus is drawn by efforts to end the violence that plagues the region.

As a political science student at Hofstra University, where I focused on national and international studies, I wrote on the Middle East conflict and participated as the chief (Hofstra) delegate at two Model United Nations held in 1977.

During these mock U.N. assemblies, we took on the role of Israel at the Princeton Model United Nations and Saudi Arabia at the Nation Model United Nations in New York City. Interestingly, the latter event actually brokered a Saudi-led peace settlement only to see the United States veto the resolution to implement the agreement that already received a “yes” vote from the State of Israel.

The nature of the conflict and events over the last generation may make the words attributed to Jordan’s King Abdullah half a century ago no longer prophetic: “Peace. Don’t mention peace for the blood that has been spilled upon it. But let the Jews and Arabs trade and there will be peace.” However, peace with Israel resulted in 30,000 new jobs and economic growth in Jordan.

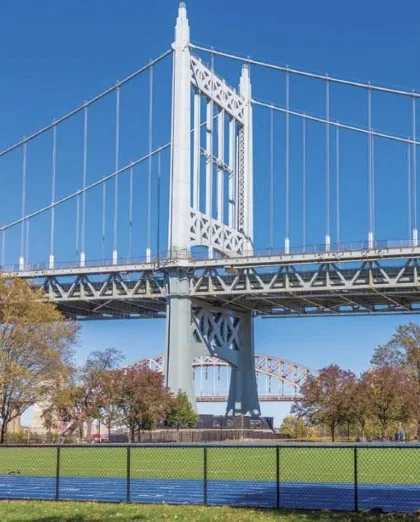

My interest in the Middle East recently drew me to a special briefing on the affairs of that area. The meeting was hosted by U.S. Rep. Gary Ackerman, who represents most of northeast Queens and adjoining Great Neck, and was held at the I-Park on Marcus Avenue at Lakeville Road in the same room in which the United Nations once met.

At the March 1 event, 40 community leaders invited by Ackerman were briefed by David Makovsky, a senior fellow and director of the Project on the Middle East Peace Process at the Washington Institute for Near East Policy. Makovsky said Prime Minister Ariel Sharon’s unilateral building of a fence offers a means to peace in the region. He opined that the fence offers protection from the terrorist bombings and makes clear who would be citizens of Israel by who gets drawn inside and outside the fence.

Interested readers can check out Makovsky’s article, “How to Build a Fence,” in the March-April issue of Foreign Affairs.

The first reports of the fence, once encouraged by our own State Department, wrongly suggested plans to encircle Arab enclaves in the West Bank. This helped fuel the U.N. resolution that referred the issue to the International Court of Justice in The Hague. Opponents of the fence call it a wall, but only 15 of the 480 miles involve an actual wall; the rest is fence.

Palestinian leader Yasser Arafat often speaks of patience instead of peace since current demographic trends show the Arab population in Israel, Gaza and the West Bank outpacing that of Israeli Jews by the end of the decade. Absent a settlement now, Arafat and his gang see an opportunity to argue democratically for majority rule over the entire geography and then do their dirty business.

Makovsky calls this losing the “battle of the bedroom.” It is one of two facts on the ground that drives the fence. The other is suicide bombings.

In 1985, Israeli Jews represented 60 percent of the population in Israel, Gaza and the West Bank. In 2000, Israelis represented 55.5 percent and demographers project further declines to 51.1 percent in 2010, 46.7 percent in 2020 and 37.4 percent in 2050, Makovsky said.

The fence does two things: It sets Israel’s borders, making clear that those across the fence cannot expect to be citizens of a larger state extending from the Jordan River to the Mediterranean Sea, and it provides security from suicide bombings. Absent terror bombings, there would be no fence.

Analyses of the bombings found the terrorists came from locations near their targets. This fact drives the fence’s installation. Where it extends beyond Israel’s borders, it protects West Bank settlements that adjoin Israel’s current border. We can expect its ultimate configuration to adjust to realities on the ground.

Though internal Israeli politics downplay it, the fence forecasts the dismantling of settlements beyond its bounds; thus, Makovsky predicts a national unity government will form.

The fence changes dynamics on the ground; it isolates Arafat and forces the West Bank and Gaza Arabs to negotiate a two-state solution. And it just may represent the best hope for peace in the Middle East.

Corey Bearak is an attorney and adviser on government, community and public affairs. He is also active in Queens civic and political circles.