The unveiling of a sign on Stockholm Street in Ridgewood on Thursday marked the blocks official dedication as one of the citys historic districts. It was the culmination of a hard-fought crusade, largely led by Pauline Leblond, one of the streets longtime residents.

There for the celebration on Stockholm Street, a block of brick row houses with porches nestled between Woodward and Onderdonk Avenues, were Queens Borough President Helen Marshall, Councilman Dennis Gallagher, Assemblywoman Cathy Nolan and members of the Queens Historical Society, who helped unveil a new street sign announcing its historic district status.

"It took hard work," said Leblond, a resident of Stockholm Street for 27 years, who led the effort for historic district designation. "You dont do these things overnight. This has taken years of never giving up."

She started a push for historic district designation many years ago, when her street was deteriorating from worn pipes and plumbing problems. With funding from former Borough President Claire Shulman and other politicians, the blocks residences, sidewalks and greenery were rehabilitated. But, in order to preserve the street, she pushed for historic district designation.

Though the block was approved by the citys Landmarks Preservation Commission more than three years ago, an official ceremony, said Leblond, was postponed due to the September 11th attacks, the War in Iraq and other pressing matters.

A historic district designation by the Landmarks Commission is a powerful preservation tool for neighborhoods fighting development that ruins their communities character. Once a neighborhood is designated, any work on the areas residences or buildings must be approved.

Simeon Bankoff, executive director of the Historic Districts Council, a preservation advocacy group that advises neighborhoods about the process of applying for historic district status, attended Stockholm Streets ceremony and said the designation was well-deserved. He commented on the streets architectural and historical significance, pointing out the repetition and uniformity of the buildings material and design.

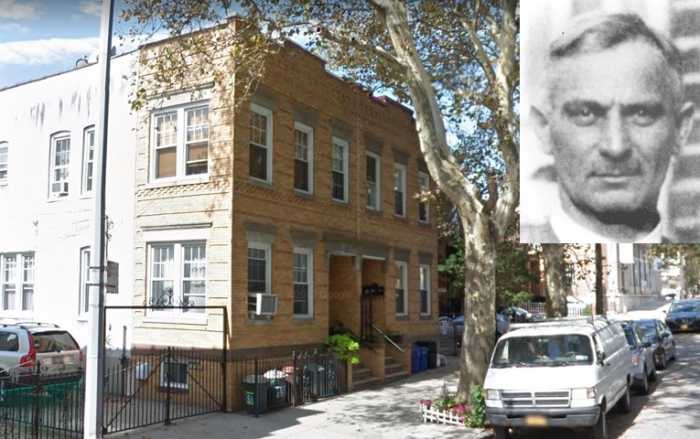

The homes on Stockholm Street date back to the early 1900s, coinciding with a boom in development taking place in Queens at the time. They were designed to accommodate working-class families in the neighborhood, who, in that period, were mostly German. Designed by Louis Berger & Company and built by local developer Joseph Weiss & Company, the rowhouses were displayed as model urban dwellings of the future, at a 1917 Pan-American exhibition in Mexico.

The homes are remarkable for their facades, consisting of iron-spot brick made by Kreischer & Sons of Staten Island, a famous manufacturer in the early 20th century.

Though many neighborhoods have applied for historic district designation with the Landmarks Commission, few have been successful. Queens is home to five of the citys 83 historic districts. The boroughs other four historic districts are Douglaston Manor, Hunters Point, Jackson Heights and Fort Totten.

Bankoff and Queens preservationists have attributed the paucity in the borough to the Landmarks Commissions tendency to be Manhattan-centric and a predetermined mindset of what is architecturally and historically significant. Bankoff noted that members of the Landmarks Commission have been schooled to appreciate communities with brownstones buildings that can better withstand the test of time more than detached single-family-home neighborhoods that pocket Queens.

At the ceremony, Bankoff spoke about other neighborhoods in Queens threatened by overdevelopment that are deserving of designation, including Richmond Hill, Sunnyside Gardens, Douglaston Hill and other parts of Ridgewood.