BY ANNA GUSTAFSON

Jere Van Dyk remembers seeing the movement out of the corner of his eye before about a dozen men wearing black turbans with rocket-propelled grenade launchers came charging down the mountainside along the Afghanistan-Pakistan border.

“I thought I was dead,” said Van Dyk, who will speak at the Central Queens YM & YWHA in Forest Hills Tuesday at 1:30 p.m. “I saw the eyes of the man who was holding the grenade launcher in front of my face, and they were cold and full of hatred. I realized I was done for.”

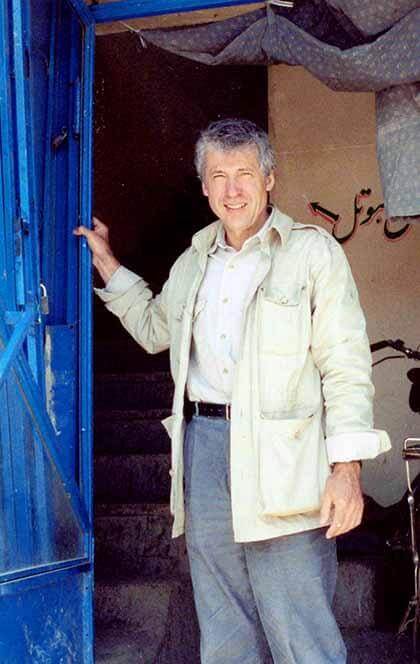

Van Dyk, a seasoned journalist who lived with the mujahideen while they fought the Soviet Union in the early 1980s, had returned to Afghanistan in 2006 to write a book about the Taliban. After having lived with the Afghans fighting the Soviet Union, many of whom went on to become part of the Karzai government and the Taliban, Van Dyk believed he could get access to Taliban leaders that no other Western journalist had managed to do.

But while trying to cross into the tribal regions of Pakistan, where no Western journalist had been for at least two decades, Van Dyk became the second American journalist, the first being Daniel Pearl, to be captured by the Taliban. For 45 days, Van Dyk was held in a 12-by-12-foot dark cell along with his translator and bodyguards, which he recounts in his recently published book “Captive.”

“It was good cop-bad cop,” Van Dyk said of his imprisonment. “On the one hand, I was treated with respect because I was a guest. On the other hand, I felt I could be killed at any moment. But they treated me always with kindness, never physically harmed me, always made sure we had food and water. They asked me questions about our culture, strange questions like if we have water buffalo, if we have rivers, do you kill people who elope, talk about sex and women.”

During his days as a prisoner, Van Dyk, who now lives in Manhattan, said he never knew if he would actually be released. At first, Van Dyk’s kidnappers told him they would free him in exchange for three prisoners at Guantanamo Bay in Cuba. Eventually, they said they would let him go for $1.5 million.

Neither of these happened, at least Van Dyk said not to his knowledge, but he believes a wide range of people, from high-ranking Taliban members to Afghan and U.S. government officials, negotiated his release. And, in some way, Van Dyk believes his captors let him go because they wanted him to write about how they had not harmed him, as is mandated by Pashtunwali, a code of honor that dictates guests — even captured guests — must be treated well.

“Many times I felt I’d never get out of there alive, and they made it clear if I didn’t convert, I would die,” Van Dyk said. “At the same time, they offered me a notebook and pen, knowing I would write about my time there. I had to make it clear to them that I wasn’t a spy, that I had come here to hear their story. They developed an understanding and a camaraderie existed. They wanted their message to get out. They made it so clear that you do this and this to us in Guantanamo, but that’s not Islam.”

Van Dyk, whose New York Times articles about the mujahideen in Afghanistan were nominated for a Pulitzer Prize and who wrote a book, “In Afghanistan,” first traveled to the country in the early 1970s after graduating from college. He immediately fell in love with the country and, despite traveling to a countless number of other countries while working for publications like National Geographic, he always ached to be in Afghanistan.

“There was something about Afghanistan that was romantic, peaceful as could be,” Van Dyk said of the country in the 1970s. “I was drawn to the freedom that Afghanistan represented away from the West. Kabul at that time was a small town, and you could hear the Rolling Stones as much as the call to prayer.”

When he returned to the country in 2006, Van Dyk said he was struck at the difference between the Taliban and the mujahideen, though he said the everyday people themselves had not changed.

“The culture is the same, the people is the same,” he said. “In the 1980s, there was a sense of solidarity, a sense of pride and a deep commitment to fight the communist infidel invaders. They certainly did not want foreigners there, such as Al Qaeda. Al Qaeda didn’t exist in the ’80s.”

Van Dyk is still haunted by his time spent as a captive. Before his release, the Taliban forced him to give them his home number in Manhattan, and they have called threatening him and his family several times.

“I still don’t know what the calls have meant,” he said. “Is it trying to establish a tie with me, hoping I’d convert, that I’d say good things about them?”

Perhaps hardest of all, Van Dyk has no idea if he will ever return to a country that has so long held in his heart, and in which he also experienced one of the most traumatic experiences of his life.

“If I returned, I would tell no one,” Van Dyk said.

The event is open to the public and individuals are asked to make a $6 donation. For more information, call 718-268-5011 or visit centralqueensy.org.

Reach reporter Anna Gustafson by e-mail at agustafson@cnglocal.com or by phone at 718-260-4574.