Seven Queens High Schools To Get ‘Turnaround’ Treatment From DOE

After a month of public hearings and six hours of deliberation at the Prospect Heights Campus in Brooklyn, decades of high school history was set aside in the name of student progress as the Panel for Educational Policy (PEP) voted late Thursday night, Apr. 26, to close 24 schools-including seven Queens high schools-as part of a Department of Education (DOE) “turnaround” plan.

The vote took place at about 10 minutes to midnight, following five hours of public comment as well as a debate between members of the PEP and representatives of the DOE, including Schools Chancellor Dennis Walcott. In almost all the votes, the members of the panel appointed by the city’s borough presidents voted against the closures, while the mayor’s representatives to the panel voted for them.

The 24 closed schools include Newtown High School in Elmhurst, Bryant High School in Astoria/Woodside, Richmond Hill High School, August Martin High School in Jamaica, Long Island City High School, John Adams High School in Ozone Park, and Flushing High School.

Grover Cleveland High School in Ridgewood and Bushwick Community High School were removed from the chopping block earlier that day. (For more information on Cleveland, see the story at left.)

These schools will close in June at the end of the school year in favor of a “new school” that will open in the same building when classes resume in September. Many of them will have new principals and staff, and teachers at the school will have to reapply for their positions. In some cases, the new principals were chosen before the old schools were closed.

All students at the old schools are guaranteed seats at their new schools.

Parent-Teacher Associations and School Leadership Teams will be dissolved and reassembled using the same methods that the DOE uses for any new school, according to Walcott and DOE Deputy Chancellor Marc Sternberg.

To be eligible for federal funds, the schools must turn over 50 percent of its teaching staff; however, Walcott and Sternberg emphasized that the schools will not be prohibited from hiring back more than 50 percent of their staffs even if it means that it would disqualify them from the federal monies.

“No principal is going to give up a million dollars to hire more than 50 percent of teachers if they do not have to,” Dmytro Fedkowskyj, the Queens Borough President’s representative to the PEP, countered. “They can find somebody else.”

“Any principal that turns down a talented educator is making a wrong decision,” said Sternberg, while Walcott would later add that “the dollar is not the ultimate goal, even though the dollar would be beneficial.”

Reasons explained

Fedkowskyj advanced a resolution- later voted down-calling on Walcott to withdraw the proposed closures and to hold a one-year moratorium on any future such “turnarounds” until the DOE offers proof of the plan’s effectiveness, stating that the current plans “may destabilize thousands of students.”

Fedkowskyj claimed that the DOE “all but eliminated this model in 2007,” only to return to it this year.

“We want models that will work and that have been proven successful,” he argued, later adding that “if this model was so good, we should have done it years ago and we haven’t.”

Sternberg provided a rebuttal.

“We acknowledge that there are strengths in these schools,” he told Fedkowskyj. “We’ve also seen and have to account for and confront some very real weaknesses.”

As an example, he pointed to August

Martin High School, which scoredaDinschoolprogressandan F in school environment on the DOE’s most recent school progress reports, which he claimed reflects “a feeling of not being safe in this school.”

“What we know is that over the last decade … the new school strategy has brought impressive, exciting new choices to families” across the city, he said.

DOE Deputy Chancellor Shael Suransky would also later add that teachers have a different opinion of their schools than parents and students, using 2011 school survey results as evidence. At John Adams High School, for instance, 54 percent of teachers have a satisfactory opinion of the school, as opposed to only nine percent of parents and only seven percent of students, he claimed.

“We have rarely heard from the many parents and kids who are not feeling satisfied,” he explained. “It is not working for hundreds of thousands of kids across these schools, and we need to fix that, and there’s an urgency to fix that.”

“The reality, overwhelmingly, in these several schools in Queens especially but citywide, is that demand has fallen precipitously,” Sternberg later claimed. “We have seen declining demand for the schools in the forms of applications through the high school (admissions) process and enrollment.”

Walcott pointed to Richmond Hill High School-whose enrollment has been decreasing and is expected to decrease further with the opening of Maspeth High School and the Cambria Heights Academy and the continued enrollment of the Metropolitan Avenue Schools Campus in Forest Hills-as an example.

“Part of the reason why we’re doing this is to create that type of demand in these buildings so we have students and parents who want to go there,” he explained.

In response to concerns from Fedkowskyj of the loss of specialized programs at the school, Sternberg again pointed to August Martin, highlighting the school’s aviation program and longtime partnership with nearby John F. Kennedy Airport.

“This is going to remain a central element of that school,” Sternberg assured the crowd, claiming that the principal chosen to run the new school at August Martin is “very committed” to the program. “It’s his- tory in that community and it’s important to students and families there.”

The April school hearings provided an opportunity for the agency to hear about similar programs of importance throughout the schools targeted for closure, he explained.

Other panelists weigh in

When asked later by Patrick Sullivan, the representative from Manhattan Borough President Scott Stringer, for more evidence that the turnaround plan is the correct move, Sternberg said that “my answer to your question … is in the plans themselves.”

“These are strategies we know work; we know when a team of educators comes together, organizes around a theory of action that they believe in,” he added. “This is an opportunity to reconstitute your staffs, to introduce new programs, to build on your strengths.”

Sullivan countered that many of the issues surrounding the schools “don’t have to do with the termination of the staffs.”

“I just don’t see the line between the solutions and the outcomes,” he added.

Wilfredo Pagan, Bronx Borough President Ruben Diaz Jr.’s representative to the panel, sounded a pessimistic note.

“At the end of the day, most of us are mindful of how the panel is set up and that most of us have our own opinions,” he said, expressing support for Fedkowskyj’s resolution. “I won’t be part of a process that will continue to break down our system.”

The mayor’s appointees to the panel, however, welcomed the turnaround plan.

“I understand how difficult it is to implement change,” said Eduardo Marti, the president of Queensborough Community College. “Leadership does matter and to have the courage to change leaders in the middle of a term, in the middle of a year, is important. But more important is changing the composition of the individuals who are teaching these students.”

“I like to believe that what is being done here-as painful as it is, as difficult as it is-I think is the right thing for the city of New York,” he argued.

“Some of these schools-not all of them-have had issues and problems for more than the past three years,” Judy Bergtraum, who works for the City University of New York (CUNY) as a deputy to the vice chancellor, stated. “I just see this as an opportunity for change and this doesn’t come very often.”

Suransky explained the criteria by which the DOE decided to save Grover Cleveland and Bushwick Community high schools from closure.

According to Suransky, after the public hearings were held the DOE looked at previous years’ grades and achievements, and located three schools that deserved a second look-the two high schools and J.H.S. 80 in the Bronx, whose relatively small showing at their hearing led the DOE to go ahead with the turnaround plan at that facility.

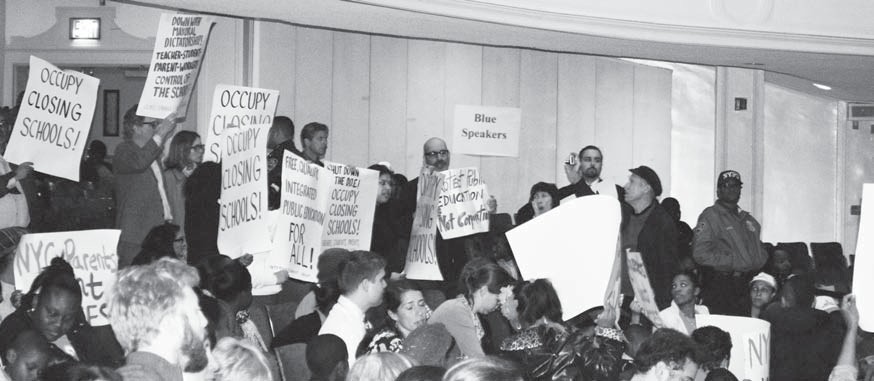

Defiance at the start

Crowds began lining up in the dreary weather to enter the Prospect Heights Campus at 833 Classon Ave. an hour before the meeting began. Among those waiting to enter was District 30 Community Education Council (CEC 30) Co-President Isaac Carmignani.

“I’m not optimistic,” he admitted. “If they voted no, it would be historymaking.”

“Changes can be made, education reform can be done another way,” he stated. “There’s another agenda here.”

Among those taking an early seat in the auditorium was Rosemary Wildeman, a guidance counselor at John Adams, who called the closures “so wrong” but expressed hope that the panel would reconsider.

She pointed out that 84 percent of the Ozone Park school’s student body qualifies for federal school lunch subsidies, and also has a large population of students with issues at home.

“We’re their safe space,” she told the Times Newsweekly.

Once the meeting began, local lawmakers were the first to beg the PEP to reverse their proposals.

“We overwhelmingly disagree with this movement, this decision,” said Brooklyn Borough President Marty Markowitz, who urged the DOE to “stop demonizing our teachers in public education.”

“I’m in favor of mayoral accountability, but not one-person control,” he told the panel.

City Council Member Elizabeth Crowley claimed that many of these schools were given three-year “restart” plans just last year, and told the panel that if they scrapped the three-year plan in favor of a turnaround, “you will be breaking promises.”

“I’m not really impressed with your brand new high school model,” she added.

“What is going on in this city is insane, and you guys are allowing this to happen,” charged City Council Member Jumaane Williams, who represents the Flatbush area. “I don’t know how you sleep at night.”

Carmignani urged the panel to wait another year to allow the schools more time to improve, asking them to look beyond statistics.

“Not everything that can be counted counts, and not everything that counts can be counted,” he stated. “District 30 is hurt by these proposals, and that most definitely counts.”

Assemblywoman Catherine Nolan, who chairs the Assembly Education Committee, expressed relief that Grover Cleveland High School, her alma mater, was removed from the list, but told the crowd that she “will not rest until all of these schools are given an opportunity” to remain open.

“These high schools have been neglected for years and it is my belief that with a little care and support, they can thrive,” she said. “‘Turnaround’ is not the answer.”

She also expressed concern that high school juniors applying for college will have to claim on their applications that they are attending a school with a different name than the schools listed on their transcripts.

City Council Member Leticia James, whose district includes the Prospect Heights Campus, told the DOE that the school closings “reflect failure, not on them, but on you.”

Parents and teachers from schools affected by the “turnaround” plan came to Brooklyn to advocate for their schools.

Among them was Paul S. Ray, a teacher at Richmond Hill High School, who asked for more evidence that the “turnaround” model is effective.

“I am not going to pretend for one minute-I don’t think anyone else is-that these are not issues of race and class we’re dealing with here,” he stated. “We are prepping a new generation to be a lost generation.”

“I am disgusted,” his colleague, fellow Richmond Hill teacher Sally Shabana, stated. “For the first time, I am embarrassed to be a New Yorker.”

Wildeman told the panel that she works with probation officers on a daily basis to ensure that juvenile delinquents get on the right path at Adams High School.

“I tell you that those children graduate,” she said. “They don’t go back to jail.”

“It’s a stable environment,” Georgia Lignau, a teacher at Bryant High School, stated of her school. “For some of our students, it’s their only stable environment.”

Rosa Aguirre, a Newtown graduate whose niece currently attends the school, accused the DOE of “decreasing the morale of the students and teachers.”

“You are all telling the students that it’s their fault,” she argued. “It isn’t, because the students keep changing, the teachers change. You know what doesn’t change? The Department of Education doesn’t change.”

Diana Rodriguez, a student at Grover Cleveland High School, led a group of students from around the city calling themselves Student Activists United in protesting the DOE’s plan.

Rodriguez presented a sarcastic defense of Mayor Michael Bloomberg’s policies, portraying herself as one of the 13 percent of minority students who are college-ready.

“Thank you so much for allowing us to be the first to experience this 100-percent foolproof turnaround plan, to be the lucky, the worthy, the successful 13 percent,” she said, later stating seriously that “in reality, we are not students for Bloomberg.”

Clidege Pierre, a teacher at Richmond Hill High School, would later tell the DOE that “I can’t say that there has been a moment when I have been prouder to be a teacher than that moment.”

Megan Behrent, a teacher at FDR High School-a school not in danger of closing-expressed solidarity with those fighting for their institutions, claiming that the DOE’s plan “is antipublic education, it’s anti-teacher, it’s anti-student, it’s anti-human.”

Some of the most vociferous advocates from the other boroughs included contingents from Lehman High School in the Bronx (whose school mascot even made an appearance) and John Dewey and Automotive high schools in Brooklyn.