When 95-year-old Bayside resident Jack Betteil was offered a free haircut and “the works” for his 100th birthday by his barber, he fully intended to take him up on the offer.

However, a diagnosis of a severe case of aortic stenosis — a condition in which the heart’s aortic valve becomes calcified with age — late last year put Betteil’s date with destiny in the balance.

After a series of testing, North Shore University Hospital cardiac physician Dr. Bruce Rutkin determined that Betteil would be a good candidate for a Transcatheter Aortic Valve Replacement Procedure (TAVR), which replaces the narrowed valve without opening the chest. The procedure, performed on April 18, was a success.

Betteil and his son Matthew returned to the hospital on July 19 to thank the doctor who saved his life.

“My father, who has such a zest for life, was having trouble breathing,” son Matthew Betteil said. “My family is so grateful that the doctors at this hospital did everything they could to preserve his life.”

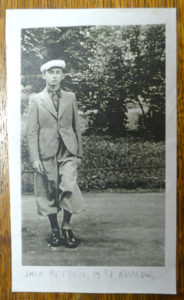

Born in Krakow, Poland, in 1923, Betteil was a teenager when he and his family were pulled from their home and taken prisoner by the Nazis during World War II. While Betteil was sent to a camp at Plaszow near his birthplace, his mother, father and two sisters were taken to Auschwitz. His sister Cesia lived; the rest of his family perished in the gas chambers.

Betteil survived six concentration camps, where he performed hard labor and was grossly underfed, before his release on May 5, 1945. He weighed 70 pounds at the time of his liberation.

“I have no idea why I survived the war,” he said. “I was very sick when I was liberated by the American army, Gen. George Patton’s Third Army. But I survived.”

Betteil spent a year in Italy at a displaced persons camp before moving to the United States, where he raised his family. He made a living repairing broken television sets.

Matthew Betteil said his father donated over 40 repaired televisions to the mental hospital at Creedmoor, near his Bayside home. The son only found out about his father’s “secret activity” after discovering a stack of thank-you notes in the basement decades later.

“It was very difficult for me to complain about anything to him,” Matthew Betteil said. “He would say, ‘You had food today. You have your parents. You have your home.’ He really taught me what was important in life when I was growing up.”

In his spare time, Betteil enjoys creating art, carving wood and sculpting his own versions of Native American statues — activities he plans to return to due to his improved health.

“I can’t just stay home and do nothing,” Betteil said.

Matthew Betteil says he believes his father’s interest in Native American arts stems from a shared experience as a population that experienced a genocide.

“I think it’s important that my father stays alive, because people who are deniers can hear the story from someone that went through it,” Matthew Bettiel said. “I think that’s another reason why — aside from him being the greatest father in the world and having him around is important to me.”