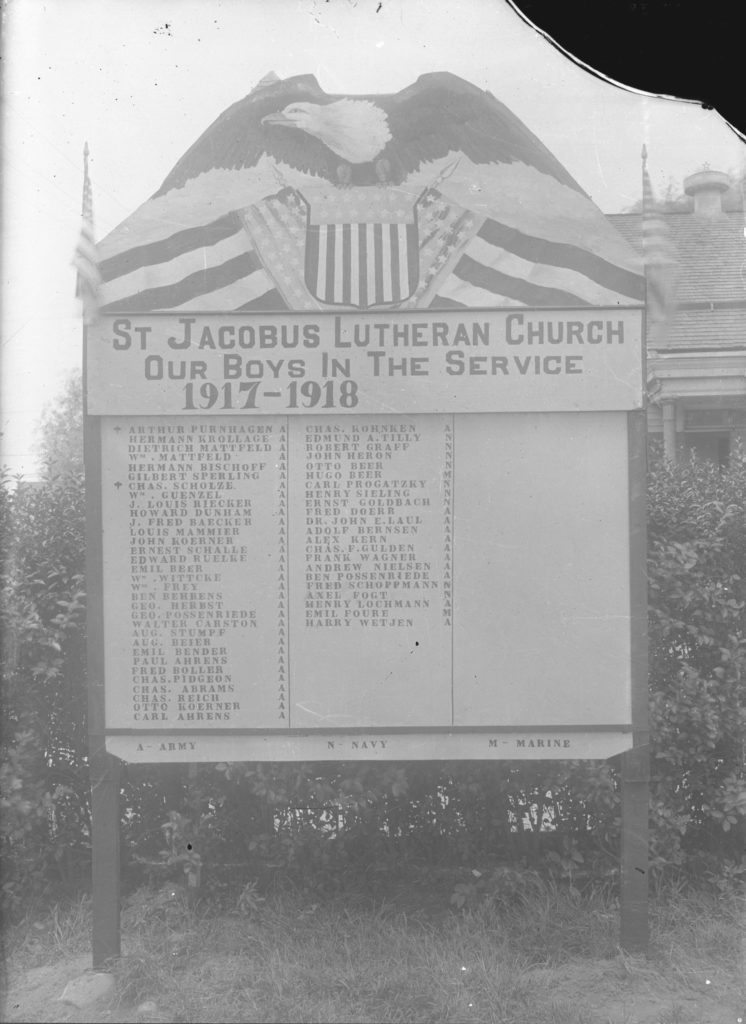

Turn the clock back 100 years ago, and you’ll find the United States in the throes of “The Great War,” the conflict that would eventually be called World War I. The U.S. entered the war in April 1917, and a number of our soldiers who went “Over There” came from Ridgewood and Glendale.

A draft signed into law by President Woodrow Wilson required that all American males between 21 and 31 years of age register for selective service. On June 5, 1917, nearly 10 million Americans registered, including approximately 41,066 from Queens County.

Selective Service Boards were established in communities across the United States with officials to review draftees and determine their fitness for conflict. Several of these boards were established in Our Neighborhood, including Board 179 located at 818 Cypress Ave. in Ridgewood, where 480 men from Ridgewood and Glendale registered.

The Aug. 3, 1917, issue of the Ridgewood Times published the names and addresses of those men from the area who had registered — the purpose of the listing being that if a neighbor knew someone should have registered and didn’t, they would be reported to the Selective Service Board for appropriate action.

Many of the men who were drafted from Ridgewood and other communities in New York were assigned to the 77th Division. Activated on Aug. 25, 1917, it became known as “New York’s Own,” and its shoulder patch included the Statue of Liberty.

In World War I, the U.S. Army employed three types of divisions: the Regular Army, which included a cadre of professional soldiers bolstered by draftees; the National Guard, which includes troops formed into regiments during peacetime who drilled as reservists within their respective states; and the National Army manned by men who were inducted into the army by their Selective Service Boards. The 77th Division was one of those National Army regiments.

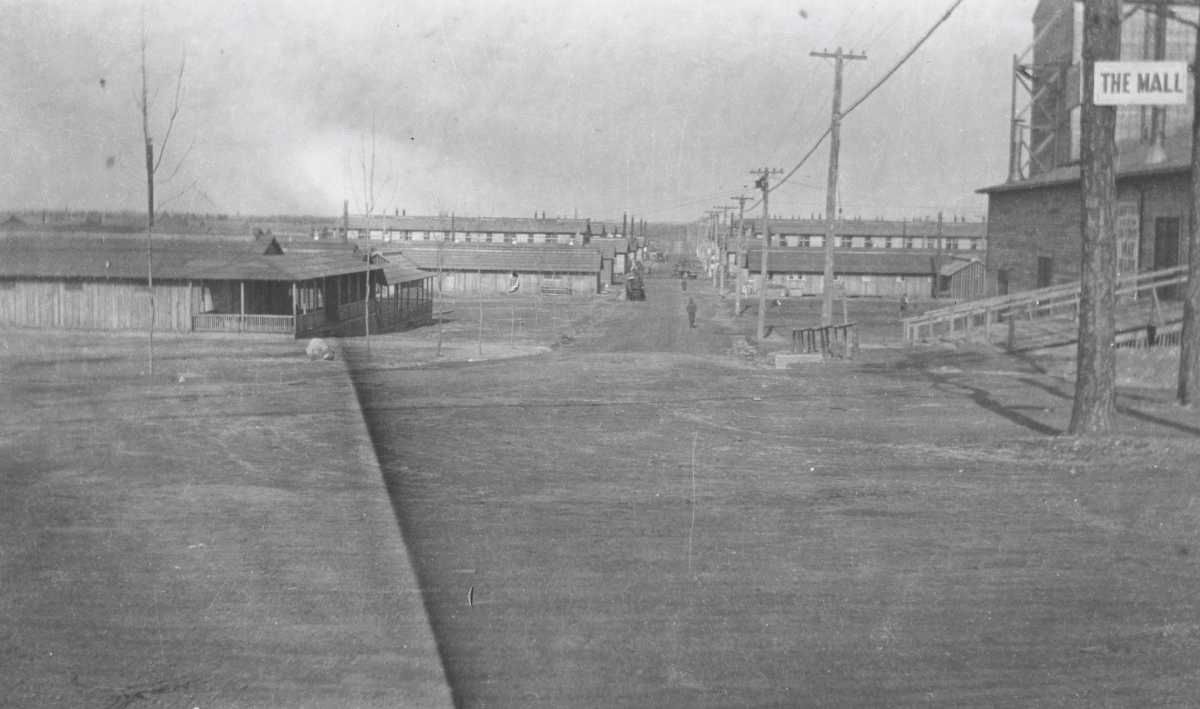

The 77th Division would be trained at the hastily built Camp Upton in Yaphank, Long Island. An army of civilian laborers were hired to construct wooden barracks to house the newly arriving troops. The first inductees reported to Camp Upton in September 1917, followed by larger numbers later in the month.

As it turned out, Camp Upton was a sea of mud, and initially there was no electricity; acetylene torches were used by the first residents until power was finally provided.

The 77th Division was organized into the 152nd Field Artillery Brigade, composed of the 304th, 305th and 306th Regiments Field Artillery; the 153rd Infantry Brigade, composed of the 305th and 306th Infantry Regiments; the 154th Infantry Brigade, composed of the 307th and 308th Infantry regiments; the Machine Gun Battalions from the 304th, 305th and 306th regiments; and the 302nd Regiment of engineers, field signal battalion, sanitary train, ammunition train and supply train.

As additional inductees arrived, Camp Upton grew to almost 26,000 officers and men. To help the recruits, the YMCA, Red Cross, Salvation Army and Knights of Columbus all installed units at Camp Upton.

After the initial training period was over, the recruits were granted weekend passes departing the camp at noon on Saturday, but they had to be back for reveille on Monday morning. The troops used the Long Island Rail Road to visit their families in New York City.

Training continued through the holidays and into the spring of 1918. Camp Upton had a mock trench, a British tank and machine gun nests installed to prepare the men for the field of combat.

Once their stateside training was completed, the first units of the 77th Division left Camp Upton on March 27, 1918, via the Long Island Rail Road; they were followed by other units in the weeks that followed.

After arriving in Manhattan, the troops boarded ships bound for Halifax, Nova Scotia, that arrived in the Canadian port city within two days. From there, they boarded a convoy of nine ships — led by a U.S. cruiser — bound for Europe. As they passed down the lane of ships in the harbor, one of them, a British battleship, had their band strike up, playing “The Star-Spangled Banner” and “Over There.”

The 12-day voyage from Halifax to Liverpool, England, proved uneventful. Upon arriving in England, the troops boarded trains that took them to the eastern coast of the island, then took a small, yet fast ferry across the English Channel to Calais, France.

When the Americans arrived in Europe, they were greeted by soldiers in uniform from armies across the globe: French, Scottish, Belgium, English, Moroccan, Canadian, Algerian, Australian, Italian, Serbian and New Zealand.

After disembarking in Calais, the 77th Division marched 8 kilometers to a camp where they unpacked, then marched back to Calais to exchange their Springfield rifles with British Enfields. They were also provided with gas masks and helmets. They were then assigned to Pas-de-Calais for 30 days of training with the British Army’s 39th Division.

In mid-May, the 153rd Infantry Brigade left for the front and marched to the trenches; a few days later, the 154th Infantry Brigade left by train and joined them at Arras as reserves for the British 2nd and 42nd Divisions.

The 152nd Artillery Brigade left Camp Upton on April 21 and made the voyage to Europe on board the Leviathan, a giant liner that was a German war prize. It left New York Harbor with 15,000 passengers — 10,000 of whom were soldiers — on April 24. Six days out, it was met by five destroyers that escorted it to the French port of Brest on May 2. The troops, along with others who arrived from Camp Upton in the days that followed, were taken to Camp de Souge for further training.

In mid-July, the 152nd Artillery Brigade left Camp de Souge on the narrow French trains to join the 77th Division at Arras. Now fully assembled, the division took over a sector in Lorraine.

Before joining their division, one of the brigade’s units, the 306th, was equipped with 155mm Howitzers, and the others were equipped with French 75s that had a highly-secret recoil system.

The 77th Division was assigned to the Baccarat Sector, which was relatively quiet, relieving a British division on June 19, 1918. Less than two months later, on Aug. 11, 1918, the 77th Division moved to Vesle near Chateau Theirry, where a few weeks earlier, a terrible battle had been fought, leading to heavy losses on both sides. It was the division’s first real test with heavy shell fire.

The division spent their first night greeted by a shell barrage of mustard and phosgene gas shells. They quickly found out that getting your mask on quickly is not as important as not taking it off too soon. Many World War I soldiers found out the hard way that it takes quite a bit of time for the poison gas to dissipate.

On Sept. 4, 1918, the 77th Division was ordered to Aisne, where they were opposed on the line by four German divisions.

Read more about the 77th Division’s World War I experience on QNS.com next week.

* * *

Among the local heroes of the war was a Marine Corps member, Sergeant Major Daniel Joseph Daly. He was born on Nov. 11, 1873, in Glen Cove, but later became a longtime resident of Glendale. Daly is one of the few soldiers in American history to receive not one, but two Medals of Honor.

Prior to World War I, he received the high honor for his defense of the American embassy in Peking (Beijing) China during the Boxer Rebellion in 1900. In 1915, he received his second Medal of Honor for protecting Americans amid an anti-government uprising in Haiti, where he had been deployed.

At the age of 45, Daly continued his proud service to the Marine Corps in France during The Great War. The French government awarded him the Croix de Guerre with Palm in 1918 for his bravery.

Daly died on April 27, 1937; five years later, the Navy named a destroyer, the USS Daly, in his honor. At the height of World War II, she was launched in 1942 from the Bethlehem Steel plant in Staten Island and commissioned into service the following March.

The USS Daly went on to play pivotal roles in the Pacific Theatre, with her crew helping the Allied forces in their island-hopping campaign against Japan.

* * *

Source: The Feb. 7, 1985, issue of the Ridgewood Times

Share your history with us by emailing editorial@ridgewoodtimes.com (subject: Our Neighborhood: The Way it Was) or write to The Old Timer, ℅ Ridgewood Times, 38-15 Bell Blvd., Bayside, NY 11361. Any mailed pictures will be carefully returned to you upon request.