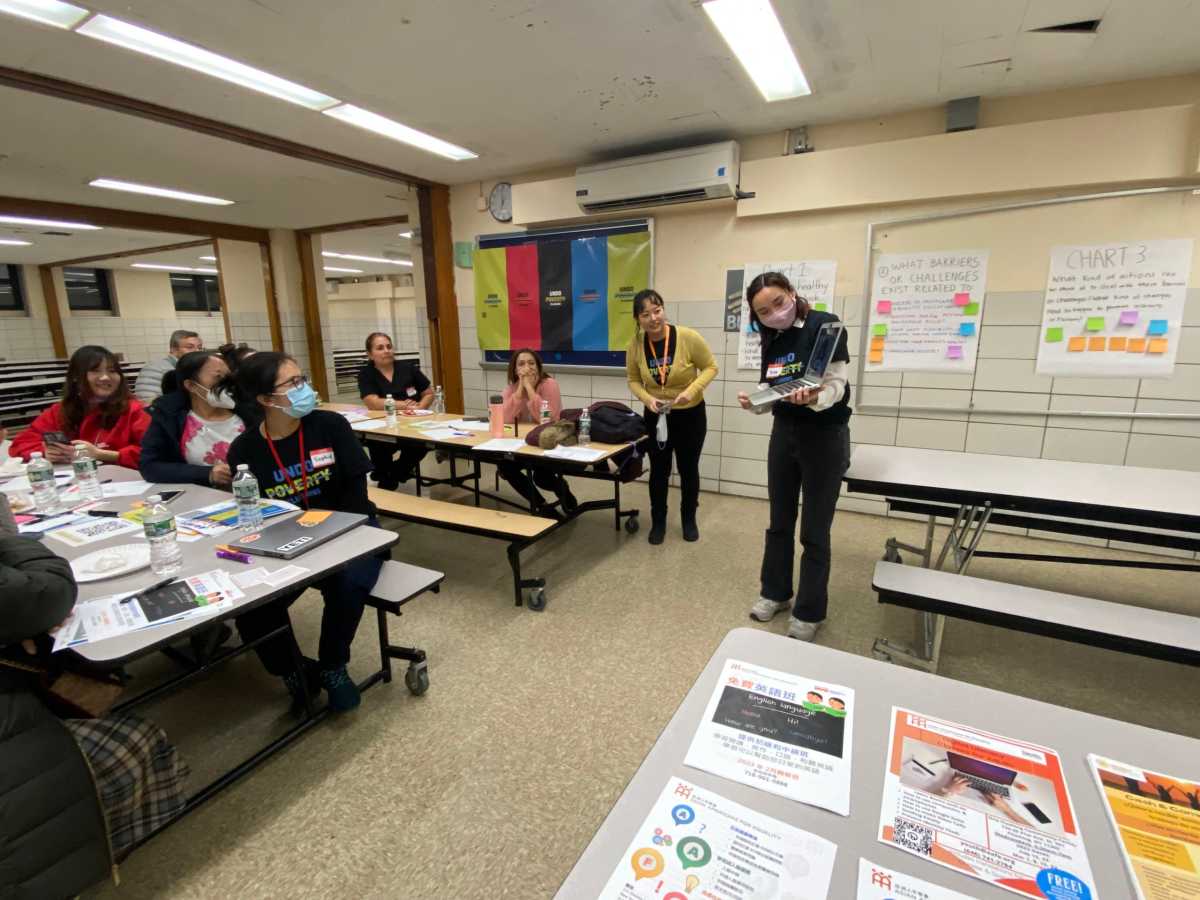

Undo Poverty: Flushing, a collaborative of six community co-leading organizations established in the fall of 2019, is working together to create solutions and opportunities that lift families and individuals in Flushing out of poverty towards sustainable economic development.

Undo Poverty: Flushing includes the Chinese-American Planning Council (CPC), Asian Americans for Equality (AAFE), the MinKwon Center, The Child Center of New York, Queens Public Library and River Fund. The collaborative is funded by the Robin Hood Foundation, New York City’s largest poverty-fighting organization. It started as the Flushing Mobility Collaborative and rebranded, becoming known as Undo Poverty: Flushing.

“We thought that it would be important to work together instead of against each other,” said Benice Mach, Mobility LABs project coordinator of the Chinese American Planning Council.

The collaborative aims to bring people in the community together to start a conversation and to understand the issue of poverty and destigmatization, according to Kevin Kang, community resources director of the MinKwon Center.

“We’re in a phase right now in our campaign where we are trying to listen to our community and understand how they themselves think about the issue of poverty,” Kang said. “I believe that, at least from our vantage point, there is definitely a shying away from the issue of talking about poverty. In the Korean community, in particular, just saying poverty is a shameful thing. At the MinKwon Center, we work to serve low-income Korean American community members and they’ll never frame it as an issue of poverty.”

According to Kang, it’s something that the collaborative is trying to change which involves multi-step, multi-layered activities, such as starting a dialogue with the community.

In October 2022, Undo Poverty: Flushing launched its Narrative Change campaign, “Poverty. It’s Not What You Think,” which was displayed on billboards, bus kiosks and posters throughout the community to break long-standing stigmas surrounding poverty.

The campaign, advertised in English, Chinese, Korean, Spanish, Hindi and Urdu, was funded by a $1.58 million grant from the Robin Hood Foundation.

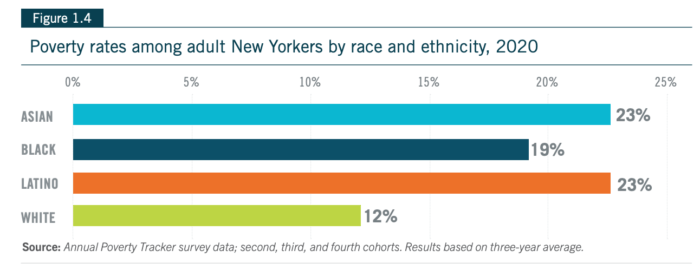

According to the Robin Hood Foundation’s Poverty Tracker, the poverty rate among Asian New Yorkers was 40% higher than the citywide average, while rates of material hardship (27%) — the inability to meet basic needs such as shelter, food and medical care — were in line with the citywide average.

Almost a quarter of Asian New Yorkers lived in poverty (23%) in 2020 versus 16% of New Yorkers citywide, according to the Robin Hood Foundation’s Poverty Tracker. The poverty rate of Asian New Yorkers was comparable to Black and Latino New Yorkers and double the poverty rate of white New Yorkers.

Among Asian New Yorkers, experiences of disadvantage — including poverty, material hardship and health problems — were especially high among those aged 65 or older, and those with limited English proficiency and those with a high school degree or less, suggesting that policies and programs serving these populations are essential.

In 2020, Undo Poverty: Flushing surveyed residents to better understand poverty in the community. The collaborative received over 500 responses with affordable housing listed as the most important issue. Other responses included deteriorating mental health and stress during the COVID-19 pandemic and lower income.

The economic upheaval brought on by the pandemic, coupled with the spike in anti-Asian discrimination and hate crimes, are likely to have serious and long-lasting negative impacts on Asian communities’ economic, social, physical, emotional and psychological well-being, according to the Robin Hood Foundation.

“We’ve seen over the course of the pandemic so much suffering within the community and across New York City,” said My Trinh Chang of AAFE. “We’ve seen folks line up at pantry lines that we’ve never seen before, a lot of unemployment, small businesses closed down and suffered. For AAFE, because we do housing and work with small businesses and do community services, we’re seeing folks facing challenges on all fronts, and it’s something we want to uplift and make sure it is talked about in the community and that there are resources available.”

According to Kang, there are people in Flushing that are experiencing poverty but don’t necessarily connect to images that are associated with poverty.

“There are people that still live in homes and are able to make ends meet, but every day it’s prioritizing expenses. The issues that are associated with poverty, whether it’s healthcare, housing or food, they’re all interrelated,” Kang said. “Every day, a person living in poverty has to make a decision on what expenses they need to prioritize over the other, whether they paid their rent on time or they have to stem off a little on their upcoming grocery shopping list.”

Kang added there’s a high rent burden in the community, where almost half of the residents spend most of their income on rent.

“What’s happening in Flushing is overcrowding, where one or two-bedroom apartments are compartmentalized for several families,” Kang said. “Flushing also has one of the highest rates of basement conversions. I think this is one of the ways Flushing families in poverty are coping, and I do believe that there is going to be a breaking point. There’s a high senior population and they’re essentially being pressured to deal with the growing inequalities, whether it’s rising rent or basic food.”

Marilla Li, deputy director of Queens Community Services at CPC, said another element they’re seeing in regard to how to act upon housing issues within Flushing, which is not specific or unique to the community, is requiring surreal legislative or policy change.

The collective has also assembled two advisory groups: a Partners Advisory Group that helps the collaborative respond in a comprehensive, cross-sector manner to the problems identified, and a Community Advisory Group where members living and or working in Flushing advise on the work of the collaborative and shape community-driven solutions.

“Those groups have been consistently showing up, bringing in more people and more voices,” Li said. “That’s another powerful element of the work. It’s not simply these established institutions. We’re also directly bringing, advocating and uplifting those voices.”

The collaborative is currently working on community listening sessions to gauge feedback from residents. While working with schools, Mach said the group realized they wanted to conduct one specifically for parents and gather educational input.

Moving forward, the collaborative is encouraging people and institutions to join in the conversation about poverty.

“There’s a lot more groups and institutions that we can engage in, such as faith-based groups and churches. We need to bring together a critical mass of people in the community that acknowledges and understands that poverty is an issue and that’s not compartmentalized in the areas of housing and healthcare,” Kang said. “These issues have been separated and have been approached in their own asylum and we’re trying to show that all of these issues are interconnected.”