The unmarked graves of two indigenous brothers were finally given headstones at Maple Grove Cemetery, in Kew Gardens, 125 years after their deaths at the hands of a government-run Indian boarding school, where they contracted tuberculosis as a result of egregiously unsanitary conditions common in these schools across the country.

The brothers, Charles Edward Jones and Harry Jefferson Jones, were forcibly taken from their family homes by federal agents at the ages of 10 and 5, respectively, to the Carlisle Indian Industrial School in Pennsylvania in 1895. They returned home gravely ill in 1900 and died within the year at the ages of 15 and 11.

According to public records, all 12 of their siblings contracted tuberculosis shortly after they returned home, as well. Of the 14 children, only two survived — Emma Jones Flannery and Rebecca Edna Hopkins Jones Dowdell Egerer. Their youngest sibling, Henrietta, died just one month after being born.

Author and genealogist Donna “Gentle Spirit” Barron, of the Matinecock and Montaukett nations, uncovered Charles and Harry’s story through extensive research, after which the Douglaston and Little Neck Historical Society and Friends of the Maple Grove Cemetery funded the headstones’ markings.

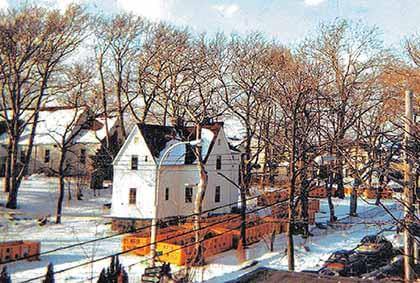

The headstones of Charles and Harry, which remained unmarked since 1900, were revealed during a ceremony hosted Nov. 22, at the cemetery. Guests gathered in the cemetery’s hall at 11 a.m. for a reception, followed by a graveside ceremony.

It was led by Chief Harry “Hunter Man” Wallace and Barron, along with members of the Unkechaug and Matinecock nations. The Shinnecock, Montaukett and Setauket nations supported the ceremony, as well.

“Every restored name is an act of remembrance,” Wallace said. “Today we bring these boys’ names forward again and acknowledge a history of separation and loss. Acts like this restore truth, dignity and connection.”

According to the National Park Service, Carlisle opened in 1879 with a mission to “Kill the Indian, Save the Man.” After the Native American genocide wiped out between 85 to 95 percent of the indigenous population — History.com estimates population declined from 50 to 60 million in 1492, before the arrival of Christopher Columbus, to 5 to 6 million in the decades following European colonization — many of them passed their culture down to their children through oral histories, native languages, cultural symbols and many other customs practiced by their respective nations.

However, in the 1800s, the U.S. federal government began mandating Native American children attend boarding schools to “assimilate” them into American society. This time, the effort was intended to commit “cultural” genocide, wiping away the culture’s identity by preventing its passing down to future generations.

More than 150,000 indigenous children were taken from their homes by force and transported to boarding schools, according to the National Centre for Truth and Reconciliation. The National Native American Boarding School Coalition estimates that by 1925, around 60,000 indigenous children were enrolled in boarding schools, which accounted for 83 percent of the indigenous children population.

Parents who refused to give their children over to federal agents were met with violence, imprisoned, or denied treaty-mandated food rations and supplies. Children returned home unable to relate to their families because they were unfamiliar with the culture and the language spoken by their parents. Many other children never returned home at all, dying at the hands of the government-funded, church-run schools.

The National Museum of the American Indian states that the environment of the boarding schools imitated military life, forcing young children to cut their hair, wear a uniform and march in formations. On paper, children were provided an education in both academics, such as math and science, as well as practical skills, such as agriculture and carpentry. They were even encouraged to participate in sports and art classes.

However, in reality, the work was backbreaking and dehumanizing. Children were forced to change their names, and they were sometimes provided with identification numbers. Conditions were unsanitary, making the environment ripe for spreading disease, which many children died from while at school or after returning home, just as Charles and Harry did.

Children were emotionally, physically and sexually abused during their time at the schools, as well as starved and humiliated. Many returned home with deep-seated trauma that led to alcoholism, displacement, suicide and a continued cycle of violence that still impacts the indigenous community today.

An investigation published by PBS News Hour states that over 3,000 children died at Indian boarding schools.

That is why organizers of the event, Nicole Schorr and Cecilia Venosta-Wiygal, said honoring the lives lost to these deadly institutions is an important part of acknowledging the past and addressing the systemic issues caused by it.

“This ceremony reflects our responsibility to understand our shared past,” Schorr said. “Restoring these markers is a small but meaningful step toward healing the generational wounds caused by that history.”