By Joe Anuta

The skyline of Queens is in for a radical makeover.

Projections for population growth in New York City tied with recovering worldwide financial markets have drawn the eye of developers to the borough. Proposals for high-rise towers and mixed-use projects are being heralded as gateways to economic prosperity, but strains on the borough’s infrastructure lurk in the background.

The transformation of Queens will not be entirely random, thanks to the foresight of concerned community members who helped rezone large swaths of the borough.

Zoning is an important way to encourage development where it is needed and discourage it where it is not, according to Paul Graziano, an urban planner who has had a hand in reshaping about half of Queens.

“Under this administration, while there was a big push to develop more density in some areas — particularly in areas that have access to transit and waterfronts — there was an understanding that other areas away from transit should be rezoned,” he said.

The initial zoning in 1961 had predicted we would be living in a city of more than 11 million people — much larger than the current population of 8.3 million, he said. And that zoning had, in the eyes of Graziano and others, given developers too much leeway in neighborhoods where single-family homes are the norm.

Beginning in 2004, Graziano and various community groups sought to preserve residential neighborhoods by enacting more restrictive zoning, which complemented efforts by the City Planning Commission to create areas of concentrated growth known as special districts, which are governed by unique regulations.

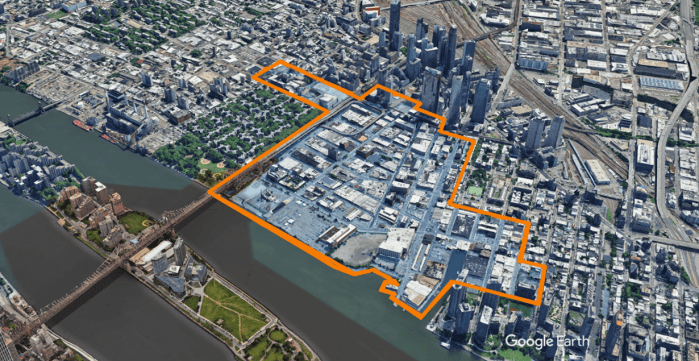

Long Island City, downtown Jamaica, Willets Point, College Point and Forest Hills are just a few districts the commission has created in the last 10 years where much of the growth will take place.

Long Island City has seen more than 40 residential developments built in the last decade, according to Gayle Baron, president of the Long Island City Partnership, and there are more on the horizon.

“If you look at economic development for the future of Queens, certainly this is one neighborhood that is going to continue to grow and prosper,” she said.

Heatherwood, a Long Island-based developer recently opened a 142-unit luxury rental building in January in the neighborhood, and Rockrose Development is constructing a 700-unit tower in addition to other properties it has built in the area, for example.

“Right now people are having bidding wars for the apartments, because there is only a limited supply,” Baron said.

Along with more housing, trendy restaurants and bars have set up shop in the area — along Vernon Boulevard, for instance — which is also home to an industrial sector, several museums and 22 hotels.

“I think it’s the whole swath of diversity that makes Long Island City interesting,” Baron said. “It still has some authenticity and some grittiness, and we like that balance.”

The Hunters Point South project, a massive mixed-use development on the Queens waterfront that will eventually feature 5,000 housing units, a school, retail and community facilities, broke ground in March. In the next couple of years, Baron anticipates the neighborhood in total will attract 20,000 new residents.

Carlisle Towery, president of the Greater Jamaica Development Corporation, maintains his neighborhood in southeast Queens is on the cusp of its own boom, for vastly different reasons.

“Our strength is not that we can be a spillover from Manhattan,” he said. “We have something they don’t, which is an airport.”

Towery hopes that downtown development options will entice commuters coming from John F. Kennedy International Airport, which is linked to the hub via the Airtrain.

Downtown Jamaica’s special district, designed for concentrated residential and commercial growth, was completed in 2007, but is only now being built out as the global economy crawls back to life, according to Towery.

“It’s five years later than what we envisioned, and that is because the economy was in shambles,” he said. “We were treading water.”

In the meantime, the corporation prepared four parcels of land that Towery hopes will further the building renaissance in the area.

The corporation recently revealed that a company called Blumenfeld Development Group is slated to bring a big-box retailer to the downtown area on 168th Street, which could draw shoppers to the corridor as a whole.

In addition, developers for two parcels on Sutphin Boulevard near the Airtrain station are also close to being announced, he said.

Details have not been made public, but between the two there will be a hotel, retail, and both affordable and market-rate housing.

Flushing, on the other hand, is a hot commercial zone that is growing without the oversight of a special district.

Flushing Commons, the controversial $850 million mixed-use project that will soon break ground on the site of Municipal Lot 1 downtown, will act as an anchor for further development, according to Michael Meyer, president of TDC Development. Like the Jamaica special district, the project was also approved just before the financial meltdown and is only now kicking into gear.

Flushing Commons, along with many other developments in the vibrant and ethnically diverse neighborhood, benefits from Flushing’s proximity to LaGuardia Airport and transit options like the No. 7 train, the Long Island Railroad and the web of highways nearby.

It is also riding the waves of an economic boom halfway across the globe.

“Discussing factors that contribute to Flushing’s success over the last 20 years also means talking about the ascent of Asia, economically, and its ripple effect,” Meyer said.

Immigrants, predominantly from Taiwan, China, and Korea, have been key to the economic success in the area, according to Meyer, whose company also constructed the Queens Crossing office building downtown and has several big mixed-use projects in the pipeline.

Sky View Parc, a 448-unit condo complex on the Flushing River, was recently rated the No. 2-selling condo in the city by propertyshark.com and it may soon have company.

A 60-acre bloc of vacant lots and industrial properties along the Flushing River may be transformed into more mixed-use waterfront development in the coming years that could feature 1,600 units of housing, 140,000 square feet of entertainment space and 95,000 square feet of retail, among other potential uses, according to the Flushing Willets Point Corona Local Development Corp.

But with a lack of special district planning, Meyer said, Flushing may be in danger of saturating itself with one type of development: hotels, for example.

The three main hubs have something in common — transit options. All three are serviced by subways and highways, and in the case of Flushing and Jamaica, the Long Island Railroad.

But there are unexpected areas of Queens that could see development booms as well.

College Point is an insular neighborhood largely cut off by the Whitestone Expressway and has existed as a mix of industrial and residential uses for decades.

Many waterfront factories, now derelict but boasting picturesque views of Flushing Bay along with less picturesque views of LaGuardia Airport and Rikers Island — could mirror a trend in Brooklyn whereby they are converted to residential properties. A plan has been on the books for years to transform the crumbling Chilton Paint Factory, on 15th Avenue at the waterfront, into a 134-unit condo complex.

And a few miles away, some of the biggest and most controversial projects in the borough are being proposed in the borough’s largest green space — Flushing Meadows Corona Park.

The United States Tennis Association is hoping to increase the footprint of its 42-acre Billie Jean King Tennis Center by less than an acre and Major League Soccer, which has been eyeing a 13-acre stadium in the green space, has teamed up with the New York Yankees and an Abu Dhabi sheikh. The partners are now looking at other possible sites.

A $3 billion plan to transform a portion of Willets Point, an area comprised of auto shops and junk yards, also features a 1.4 million-square-foot mall planned for the parking lot of the New York Mets’ Citi Field, which is technically parkland leased to the team owners.

The opposition to these plans has been vocal. A host of civic organizations have criticized the Bloomberg administration for failing to consider how these projects, as a group, will affect traffic and congestion in the area.

Still, questions remain for other areas of the borough. Prior to Hurricane Sandy, the Rockaways enjoyed an increased influx of day-trippers to its beaches, but many property owners are struggling with the question of whether or not to rebuild.

A large technology graduate institution run by Cornell University and the Technion-Israel Institute of Technology is proposed for Roosevelt Island, and planners are looking to western Queens for potential office space for the additional startup companies that will likely spring out of the campus.

Some of the plans for development seem likely to succeed, others are thawing out from the 2008 collapse and still others may be destined for the dust bin of history.

In Flushing Meadows Corona Park, for example, various generations have proposed a race car track, a football stadium and an Olympic rowing lake, all of which have failed, which goes to show that there still may be some surprises in store for the borough’s skyline.

Reach reporter Joe Anuta by e-mail at januta@cnglocal.com or by phone at 718-260-4566.