Long Island City bid farewell to its unofficial mayor on Tuesday as hundreds attended a Mass of Christian Burial at St. Mary’s Roman Catholic Church on Vernon Boulevard.

Frank Carrado was a beloved link to the past of what is now the fastest-growing neighborhood in the country prior to his death last week following complications from a stroke. He was 89.

“Frank was many things for our neighborhood. Historian, community advocate and unofficial mayor,” Hunters Point Civic Association President Brent O’Leary said. “He was a lovely person always ready with a story and to lend a hand. He will always be part of what makes this neighborhood special.”

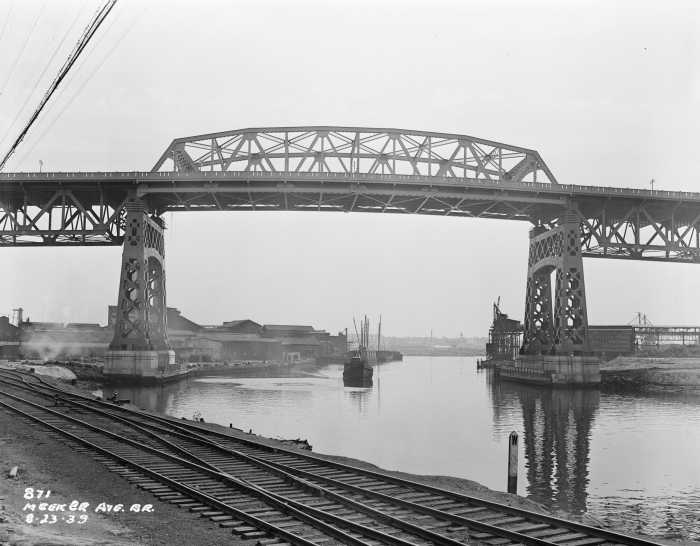

Before there were towering luxury apartment buildings along the waterfront along the East River, Long Island City was the gritty soot covered industrial center of Queens where Carrado grew up and lived his entire life. He watched the neighborhood change over the decade through the viewfinder of his camera and his photography hangs in building lobbies, bars and restaurants around the neighborhood.

And he was always ready with a story.

“I go so far back in this town that I remember there used to be a community bathhouse,” Carrado said in a 2014 interview. “It used to be right next to the Fire Department on 47th Road. Nobody had their own showers back then.”

The “mayor of LIC” recalled a time when he was a young boy back in the 1930s and 1940s when factory smoke stacks belched out so much soot it would cover the entire neighborhood.

“It would be everywhere, on the cars, the buildings; you could not even hang out your laundry on the clothes line because it would get all black,” Carrado wrote in a letter to QNS in 2011. “If you walked out of your house you would think you were walking on the moon as the soot would cover the sidewalks, too. That was really something to see.”

Carrado saw much during his life in Long Island City and he loved to talk about his memories such as the East River being so polluted “you could walk on top of the garbage.” As a 10-year-old boy, Carrado and his buddies would wait down by the railroad between Vernon Boulevard and Fifth Street like Spanky in the old Our Gang TV series.

“When a train would come in, my friends and I would climb up on the train and get a 50-pound bag of coal. We would carefully get down and carry the bag around to our neighbors’ houses,” he wrote. “Coal was very important because it was the way people would heat their houses back then. We would go around and sell the coal for 50 cents. That was a lot of money to us back then. We had a great business going.”

Back then, the neighborhood was primarily Irish and Italian, Carrado recalled.

“Everyone intermarried. The Irish women didn’t like the Irish men’s drinking habits, so they married the Italians and the Italian women didn’t like the Italian men’s temperament, so they married the Irish,” he said.

Corrado also remembered when Italian prisoners of war were held on the Brooklyn side of Newtown Creek during World War II.

“They were harmless and were allowed to visit on weekends provided they wore an armband to identify themselves,” he said, adding that several of the prisoners stayed after the war and opened small businesses. Carrado watched as the Irish and the Italians began to age and die out to be replaced by a much younger demographic soon after 2000.

“That’s when all the factories started coming down, the old Pepsi factory and Admiral TV, they all came down and these high-rise apartment building started going up,” Carrado said.

Unlike many of the neighborhood’s elder gentry, Carrado enjoyed the company of the newcomers to Long Island City. He would even show them the ancient manhole covers in front of the 108th Precinct on 50th Avenue.

“Today 80 percent on Long Island City are between the ages of 20 and 50 and it’s not just people,” he said. “Back in the ‘50s we had 10 dogs. Now there are thousands and they even have their own day care centers.”

Carrado’s wife predeceased him, and he is survived by his daughter Ann Marie and three grandchildren. His interment was at Calvary Cemetery, not far from the neighborhood he loved his entire life.

“My wish was that he would have been recorded by the Queens Public Library for their living history series,” Friends of Hunters Point Library President Mark Christie said. “When he fell ill, I knew that wouldn’t happen. It breaks my heart.”